In the commentary leading up to the June meeting, I argued that some relaxation of the tariff issues with Mexico, combined with relatively good data for the US economy, would make the FOMC’s decision to hold pat on rates relatively easier.

While the FOMC did decide at its June meeting to hold rates constant for the moment, the dot charts and dissent by President Bullard suggest that a number of participants were closer to cutting rates than they may have been previously or than observers might have expected leading up to the meeting. The statement itself, as many have noted, deleted the word , and the FOMC also dropped its characterization of ongoing economic activity from “solid” to rising at a “moderate rate.” We need to remember that the minutes of the March meeting indicated that the staff forecast had included a markdown of growth after Q1, so the change in language validates that forecast and aligns with the districts’ characterization of growth in their regions.

The deletion of the word patience really reflects two considerations. First, the Committee expressed concerns that downside risks had increased, and Chairman Powell made it clear in the press conference that those concerns were driven by uncertainty about US tariff policies and global growth. The FOMC statement did note that inflation expectations for the near term had declined, but longer-term expectations remain well anchored. Clearly, the failure to achieve its inflation objectives was not a determining factor in the FOMC’s decision to maintain current rates.

Second, while the word patience was missing, it was also the case that policy would be dependent on incoming data, and that view hadn’t changed one bit. Instead, the deletion of patience indicated the FOMC’s concern about the risks to the expansion and reflected the Committee’s shift from a “steady as you go” policy stance to “on your mark.”

How far are we from “get set, go!” is now the critical question; and at this point, as former Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia President Charles Plosser noted on Bloomberg Asia after the meeting, we are rather in the dark as to what the FOMC’s reaction is likely to be to the incoming data. The key incoming data for the FOMC’s July 29–30 meeting will the June jobs report on July 5 and the first look at the advance estimate for Q2 2019 GDP on July 26.

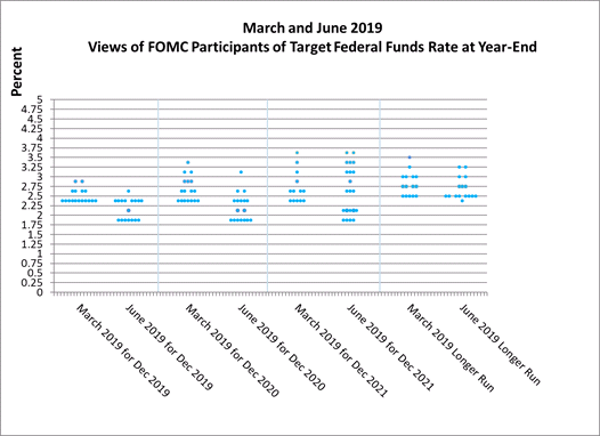

We can also glean some useful information on how the FOMC participants’ views on policy have changed from a comparison of the dot plots from March to June.

First, looking at the December projections, we see a significant shift and difference of opinion as to whether rates should be raised or lowered. While six people favored at least one or two rate increases in March, all but one had significantly lowered their rate recommendations in the June SEP. Eight people continued to favor holding rates between 2.25–2.5%, while all the remaining participants favored at least one rate cut by the end of 2019. Similarly, for 2020, of the 10 participants who saw rates above 2.5% in March only three now saw rates that high, while nine saw rates below 2.25%, and seven saw rates between 1.75–2.0%. Finally, for 2021, views have further diverged, probably reflecting the uncertainties that participants now feel may exist after the 2020 election. These projections appear quite bearish, given the fact the interest rates have come down in the near term from where they were in March. Mortgage rates are now hovering at about 3.9%, more than a percentage point below where they were at the end of 2018. More generally, the Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index is almost as low as it was in 2007 before the Fed started to raise rates. Given the state of the labor market and general health of the economy, it remains a puzzle as to why the FOMC has now changed its view regarding the appropriate path for interest rates going forward.

1) It is now clear in Fed-speak that solid means that growth is faster than “moderate,” which usually means growth at about 2.2–2.4%.