Over the last month, it appears that the crowd has now taken full swing from the economic ‘hard’ landing view to the ‘soft’ landing view.

Q2 gross domestic product (GDP) came in higher than expected at 2.4%. The employment data came in stronger. And the U.S. consumer confidence index jumped to 117 – a two-year high.

So, everything looks fine and dandy, right?

Well, I’m not so sure.

It’s true that some of the data have shown resilience. But there’s also a lot of data that’s been discounted by the market.

Most notably – consumer credit growth, U.S. imports, and corporate profits.

Let’s take a closer look at all these to get a clearer picture. . .

U.S. Consumer Credit Growth Isn’t Looking So Good

Consumer credit – aka consumer borrowing or household debt – plays a significant role in influencing an economy in various ways.

Why?

Two reasons: the U.S. is a highly consumer-driven economy (making up roughly 70% of annual GDP). Consumer credit drives excess demand.

For instance –

1. Consumer credit allows individuals to purchase goods and services even when they lack income. This, in turn, boosts consumption and increases demand for products, leading to increased economic activity, and so on.

Many big-ticket items – like homes and automobiles – can’t be purchased on the back of wage growth alone.

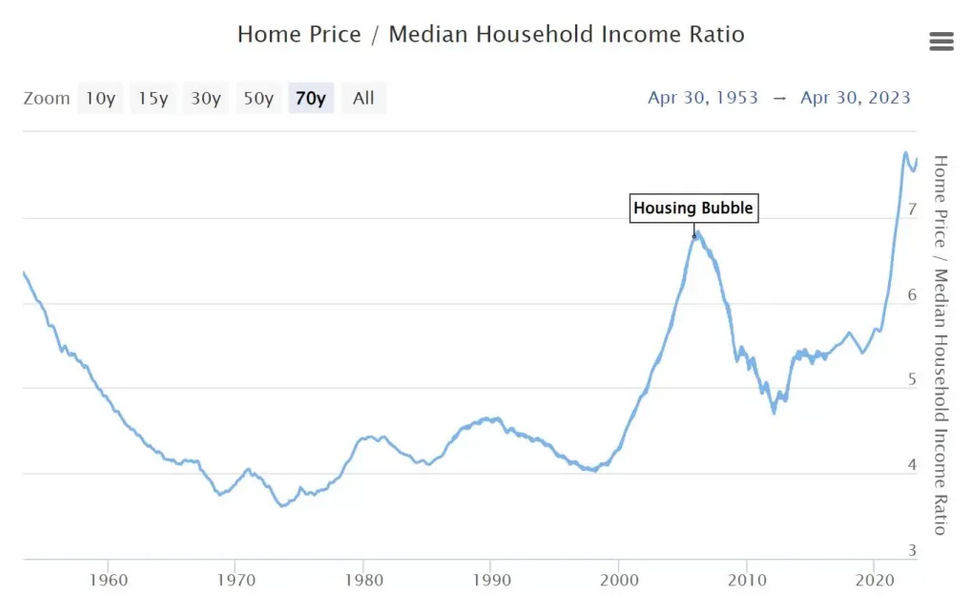

For example, the home-price-to-household-income ratio is already 7.69. Meaning it would take roughly eight years of all pre-tax income to afford a home. Thus buyers depend on access to credit instead.

2. Consumer credit can indirectly influence business investment.

See, when consumers have access to credit, businesses may experience higher demand for their products, encouraging them to expand production capacity and invest in new technologies – fueling demand further.

3. When consumer credit is readily available and consumers are willing to spend, it can contribute to inflationary pressures.

Increased demand for goods and services can drive up prices, leading to a general rise in the cost of living (aka more credit leads to more demand, thus pushing prices higher).

So when consumer credit declines, it does the opposite (it’s deflationary).

4. Finally, increased consumption resulting from more credit stimulates economic growth.

Because – as the above mentions – when households spend more on goods and services, businesses experience higher sales and, in turn, invest more in production, creating a reinforcing cycle of economic expansion.

Thus consumer credit data is an essential economic indicator monitored by policymakers and financial institutions. Because changes in consumer borrowing patterns can provide insights into the overall health and direction of the economy.

Put simply – the credit cycle plays a key role. Since more consumer credit reinforces an economic boom. And less credit reinforces an economic bust.

So, how does consumer credit look today?

Not very good.

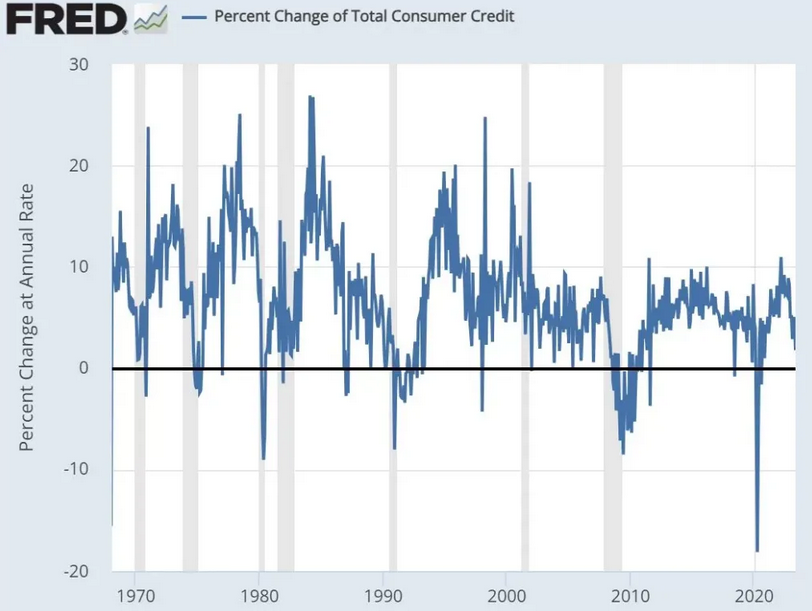

For perspective – U.S. consumer credit growth in May 2023 was just 1.7% year-over-year – its lowest level since October 2020.

In fact – according to Bloomberg – May saw its largest monthly consumer credit decline in over two years (total credit rose just $7.2 billion, but was expected to reach $20 billion).

And non-revolving credit – such as loans for school tuition and vehicle purchases – fell $1.3 billion, the first decline since April 2020.

So as banks continue curbing new lending, it’s also clear that loan demand is declining.

And this isn’t a boon for the economy since credit drives so much excess demand.

Or – said another way – wages alone can’t justify the current consumption.

Take away the credit, take away the demand. . .

U.S. Imports Are Negative Year-Over-Year – Showing Reduced Demand And Pressure For Global Economy

This shouldn’t come as a surprise, but the U.S. is a massive trade deficit-running country.

Meaning it consumes far more than it exports (nearly $1 trillion worth annually).

A strong U.S. dollar allows cheaper imports – a benefit for consumers – but comes at the expense of U.S. manufacturing and exports.

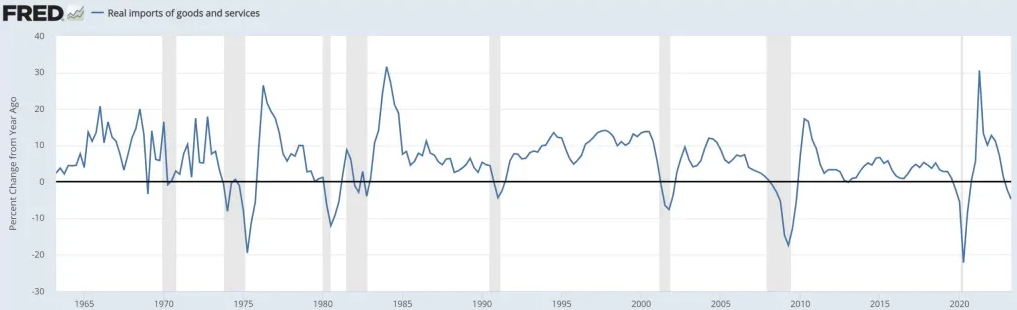

But U.S. real imports of goods and services in Q2 have plunged -5% year-over-year – the only time it’s been negative since 2020, 2009, and 2001 in the last 23 years.

This shows us that demand for foreign goods is easing as U.S. consumers temper their spending on goods in favor of services and experiences.

It also suggests that the drop in inbound shipments indicates U.S. firms are focused on getting inventories more in line with sales.

This contributed to Q2’s GDP growth (a smaller deficit).

But while U.S. consumers and businesses import less, it means less aggregate demand.

Now, it’s true that this is more of an issue for global economies – like China, South Korea, Japan, Germany, etc – since they depend on exports for growth.

Thus as U.S. imports drop, those countries will feel that pain more.

Why? Because those countries don’t have strong consumer shares of GDP – meaning if they can’t consume what they produce at home, they must export the rest.

But if the U.S. – the world’s largest deficit-running country – sees demand for imports declining, those countries will struggle. Either through greater deflation or unemployment as unconsumed goods pile up.

The main takeaway here is that as U.S. consumer demand for imports drop sharply. Indicating cooling demand domestically. This will ripple through and negatively affect other major economies.

To put this into perspective, U.S. real (inflation-adjusted) retail and food service sales have been flat for the last 28 months.

Thus real consumption hasn’t exactly grown.

But debt sure has.

U.S. Corporate Profits Sink Negative – And Look To Fall Further (Here’s Why)

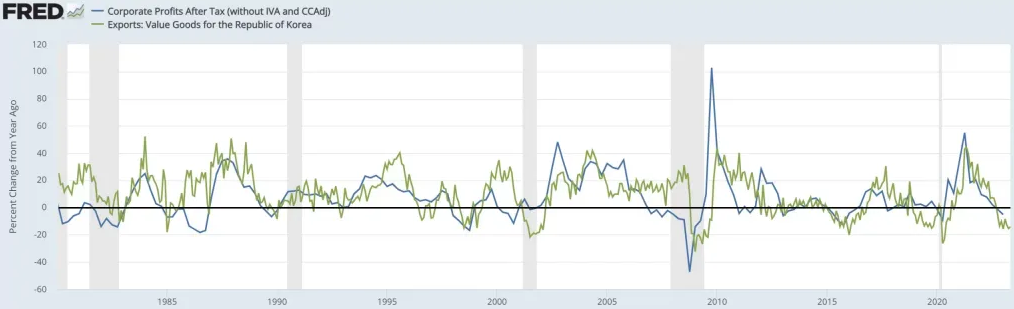

U.S. corporate profits (after tax and without adjustments) have eroded sharply over the last year.

For instance – as of Q1-2023 – corporate profits have plunged -5.13% year-over-year.

And it appears likely this trend will continue.

Why?

Well, just take a look at South Korean Exports.

As I’ve written about before – South Korean exports are considered the ‘canary in the coal mine’ (aka an early indicator of trouble) for corporate earnings.

Why? Because there’s been a tight correlation between South Korean export growth and corporate profits over the last 40 years.

To give you some context, South Korea is Asia’s fourth-largest economy and supplies the world with a wide variety of goods, making it a major hub for international trade activity.

Thus when South Korean exports move sharply one way or another, global profits usually follow closely behind it (usually with a 12-month lag).

Or – said another way – if South Korean exports increase, so do global profits. And if they decrease, profits decline.

Now, it may sound odd that global earnings seem to follow South Korean exports.

But it’s empirically true.

And this is what makes South Korean export growth one of the most important leading indicators in the world.

Just take a look at South Korean export growth (green) vs. U.S. corporate profits (blue). They tend to follow each other.

And with South Korean exports cratering -16.5% in July – hitting their steepest decline since May 2020 and have now remained negative for the last ten months straight – U.S. and global corporate profits look to see further downside.

In fact, South Korean exports to China fell –25.1%, and those to the US fell –8.1%.

With China sinking into a balance sheet recession (I’ve written about this recently – read here), and now U.S. imports turning negative, this isn’t exactly great for corporations.

Making matters worse, there’s already a massive wall of corporate debt maturing over the next 30 months that is ‘BBB-rated’ – meaning just one downgrade away from hitting junk status.

Thus a continued decline in corporate profits could be a serious issue for corporations getting downgraded – raising their borrowing costs and financial fragility further.

Something to keep an eye on as demand continues cooling around the world.

In Conclusion

While the media pundits parade the soft-landing thesis, I’m not convinced we’re out of the woods yet.

Fading consumer credit, sinking U.S. imports, and eroding corporate profits all indicate some issues.

But of all this, I believe declining credit demand is the biggest thing to focus on.

Because less consumer demand for debt indicates less consumption, which will impact corporate earnings and U.S. imports.

Now, there is another option. . .

I’ve seen many talk about rising real wages as deflation mounts (aka giving consumers more purchasing power).

And while that’s true, there’re two important things to keep in mind:

1. Deflation amplifies the burden of debt on both individuals and businesses.

In a deflationary environment, the real value of debt increases as prices decline. This means that borrowers must dedicate a larger portion of their real income to repay debts, leaving less money available for spending and investment.

And as debt becomes increasingly burdensome, defaults rise, leading to a contraction in credit availability and further weakening economic activity.

The debt deflation spiral can have severe consequences, as witnessed during the 1930s Great Depression,1991 in Japan, the 2008 global financial crisis, and China recently (post-2022).

Put simply, deflation in an over-indebted economy is a recipe for crisis.

2. If there’s no demand for credit, then businesses must either slash prices to levels that consumer wages can justify or scale back output. Potentially losing market share and crushing profit margins.

Since the 1980s, we’ve seen companies – such as General Motors (NYSE:GM), Ford, General Electric (NYSE:GE), Sears, etc – all turn towards extending credit to move inventory without slashing prices.

They’ve all essentially become banks.

For example, every time you go into a Macy’s, I’m sure you’ve had them ask you to sign up for a credit card.

That’s because they want to gain the interest income as well as have you buy more now.

This shows how deep credit’s grown as a means to drive demand. And how any decline in credit has wide-spreading ripple effects.

So, I don’t believe the economy hitting a soft landing is an assured thing.

In fact – after seeing recent consumer credit demand and plunging bank lending – I’m more worried than before.

But as always, time will tell.