The concept of socially responsible investing (SRI) has been around for hundreds of years. From the Quakers (aka, the Religious Society of Friends) prohibiting members from participating in the slave trade in 1758 to the exclusion of “sin stocks” in the 1920s to supporting the civil rights, environmental, social, and anti-war movements in the 1960s to the modern day focus on Environmental, Social, and Governance investing practices—which takes a holistic view that helps stakeholders understand how an organization manages risks and opportunities related ESG criteria—investors have been looking for a way to both achieve reasonable returns while at the same time reflecting their social, political, and/or religious expectations and beliefs.

In 1928, the Pioneer Fund (PIODX) was the first publicly offered socially responsible mutual fund in the U.S., which screened out tobacco, alcohol, and gambling investments. Since then, and with the rising popularity of ESG accounting standards and declarations, responsible investment (RI) practices have continued to evolve. While in the beginning virtually all SRI portfolios were constructed using negative screens to avoid investments contrary to defined ethical guidelines, many of these portfolios underperformed their benchmarks. Many “sin” stocks and related industries the portfolios had excluded often did very well during certain market rotations. Even though some investors were willing to accept underperformance from their portfolio so they could sleep well at night, most still wanted a reasonable return.

Today SRI is often referred to as socially conscious, ethical, green, mission, religious, sustainable, impact, or ESG investing, all having strategies that screen out weapons manufacturers, gambling establishments, tobacco companies, abortion-related securities, pornography, etc., or that screen in best-in-class shareholder-friendly companies. Whatever their cause, SR investors seek two things: reasonable returns and targeting special social causes.

There are three basic methods to select a company for inclusion into an RI fund. The first, as mentioned earlier, is the negative screen. The second method is the positive screen, where the fund manager chooses companies that engage in a particular activity: corporate social responsibility, development of solar power, promotion of women in the workplace, or some combination of attributes. The third method is a restricted screen in which a manager may select a firm that, because of its diversified structure, might have activities in a less-than-desirable sector, but the rest of the firm’s activities are acceptable to the manager. This last method may also include investing in organizations that have a tilt in the right direction, that is, organizations that have made strides to improve their greenhouse gas emissions or that have reduced their dependence on coal.

Interest in RI mutual funds has grown considerably over the last almost three decades. In 1994 there were only 56 unique funds (ignoring share classes), with combined total net assets (TNA) of just $4.0 billion. By June 30, 2022, those numbers jumped to 745 unique funds with a combined value of $576.8 billion. Perhaps as important is the proliferation of diverse investment options available to SR investors to help them create a well-diversified portfolio. In 1994, there were 28 classifications from which to choose RI funds. However, as of June 30, 2022, the number of classifications in which one could find socially responsible and ESG funds jumped to 105, with representation in each of the major asset classes: equities, fixed income, mixed assets, money markets, alternatives, and commodities.

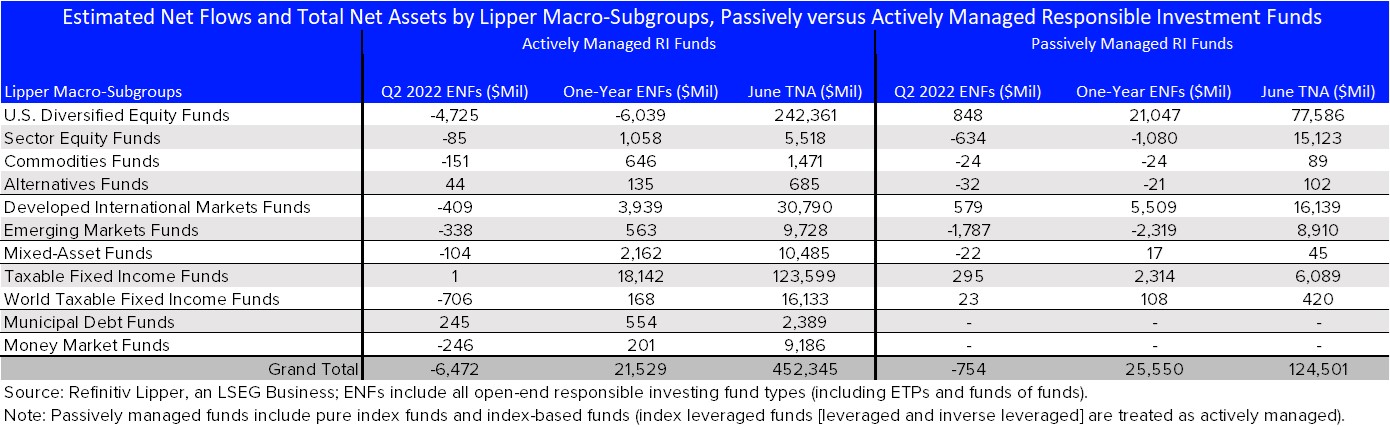

Somewhat by definition, SR funds were generally actively managed. However, with the increased focus on ESG accounting standards and practices, we see a proliferation of passively managed SR funds and ETFs as well being offered, which aim at providing investors with a low-cost, tax-efficient option in the space. As of June 30, 2022, actively managed SR funds accounted for a little more than 78% of the socially responsible assets under management, while their passively managed counterparts made up just little under 22%. And in line with trends we have seen in the non-SR open-end funds space (which include ETFs), flows have been significantly positive in the passively managed U.S. Diversified Equity (USDE) Fund classifications (such as Large-Cap Growth, Multi-Cap Value, or Small-Cap Core Funds, for example), while their actively managed counterparts have suffered net redemptions.

In the table below, both actively and passively managed RI funds witnessed net outflows during Q2 2022, handing back some $6.5 billion and $754 million, respectively. However, the passively managed socially responsible USDE funds (+$848 million), developed international markets funds (+579 million), taxable bond funds (+$295 million), and world taxable bond funds (+$23 million) macro-groups significantly outdrew their actively managed socially responsible counterparts.

Despite the recent market meltdown, it doesn’t look like socially responsible investors were any more likely to turn tail on their selected funds than their non-SR focused counterparts, with both groups seeing about an 11.6% decline in asset under management—part of that was due to market declines rather than just net outflows. At the end of March 31, TNA in SR funds was $652.5 billion.

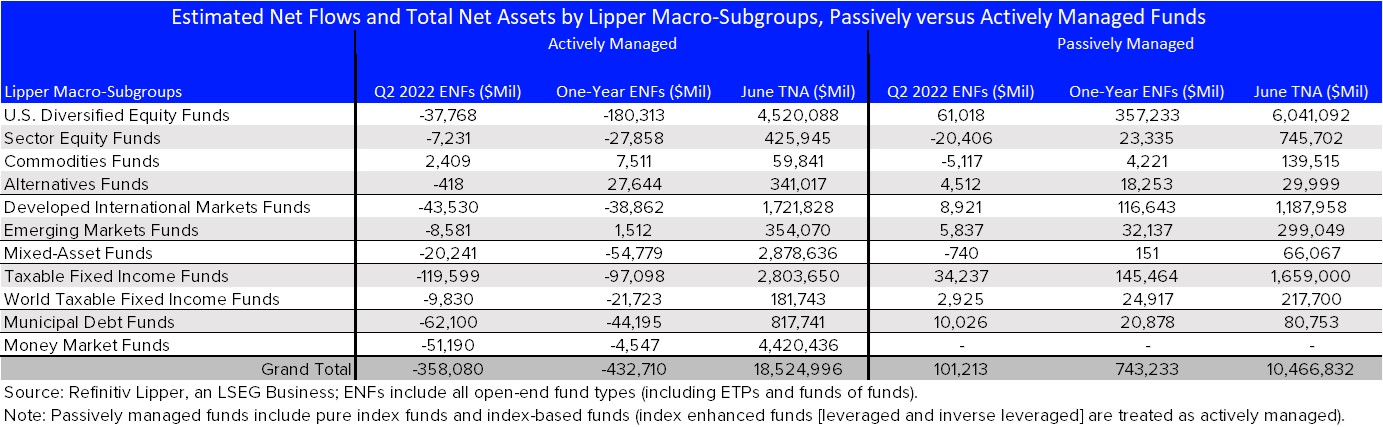

Encouragingly, we see that for the one-year period ended June 30, 2022, actively managed RI funds attracted $21.5 billion, while the passively managed RI counterparts took in some $25.6 billion. This contrasts with the pattern we see below, where passively managed funds (+$743.2 billion, ignoring RI status) attracted net new money, while their actively managed fund counterparts (-$432.7 billion) suffered net outflows for the one-year period.

Nonetheless, the same passively versus actively managed trend described above for USDE funds remains in play at the one-year mark for RI funds, where passively managed USDE funds (+$21.1 billion) attracted the lion’s share of net money, while their actively managed counterparts (-$6.0 billion) suffered relatively large net redemptions.

With the recent increase in the relative importance in ESG investing trends and reporting standards (see the SEC’s proposed rule for Enhanced Disclosures by Certain Investment Advisers and Investment Companies about Environmental, Social, and Governance Investment Practices) and more investors climbing on the ESG bandwagon, we wonder if investors will be as committed to their social responsible causes as they have been in the past, or will investors more likely be influenced by short-term return trends—running for the exits when markets turn? Looking back at previous segments we have written about SR investing, we commented on the fact that during big downturns (dot-com bubble and 2008 financial crisis) that SR investors were more likely to stay the course than their non-SR-focused counterparts.