The Treasury market continues to price in rising expectations that the recent inflation surge is temporary. No one knows if this implied forecast will prove correct, but for the moment the moderate slide in 10- and 30-year Treasury yields reflects a crowd that’s inclined to take an ever-more skeptical view of the reflation trade, if only on the margins.

Let’s start with the benchmark 10-year yield, which continues to trend lower after peaking in late-March. In Wednesday's trading (June 23), the 10-year rate ticked up to 1.50%, which is still close to the lowest level in four months.

The 30-year yield bounced a bit more after swooning late last week, but a downside bias remained intact.

The downward drift in rates revived bond portfolios after a rough first quarter. The iShares 7-10 Year Treasury Bond ETF (NYSE:IEF), for example, continued to trend higher.

One school of thought that’s created some headwinds for the reflation trade lately revolves around the idea that the Federal Reserve may turn hawkish earlier than expected. Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan gave support to this idea in an interview yesterday, saying that the first rate hike may arrive at some point next year.

In an interview with Bloomberg Wednesday, Kaplan stated:

“As we make substantial further progress, which I think will happen sooner than people expect—sooner rather than later—and we’re weathering the pandemic, I think we’d be far better off, from a risk-management point of view, beginning to adjust these purchases of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities."

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard offered similar remarks in recent days, suggesting that the central bank was rolling out a coordinated effort to minimize the surprise factor for an earlier-than-forecast start to tighter monetary policy.

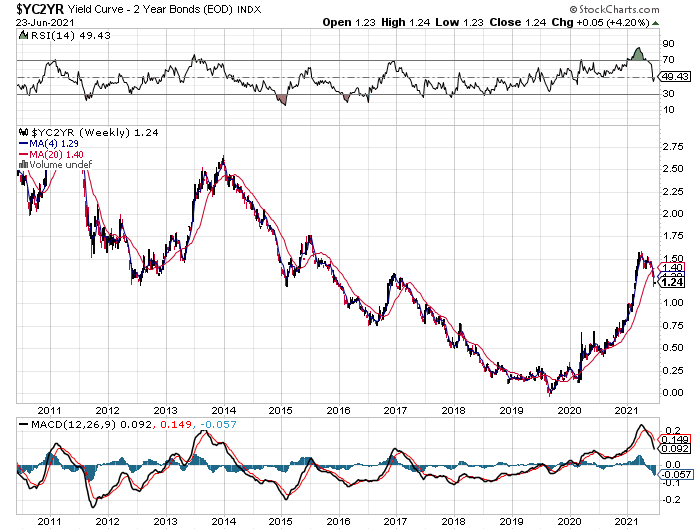

Such comments appeared to be resonating at the shorter end of the Treasury curve. The 2-year yield—considered the most sensitive maturity for rate expectations—has recently shot higher, presumably lifted by an attitude adjustment on rate-hike timing.

Incoming economic data will be the final arbiter of how Treasury yields trend in the weeks ahead, but for the moment there’s a growing sense that the Fed is laying the ground work for a more hawkish stance, albeit mildly so, but no less conspicuous relative to policy decisions that prevailed during the pandemic.

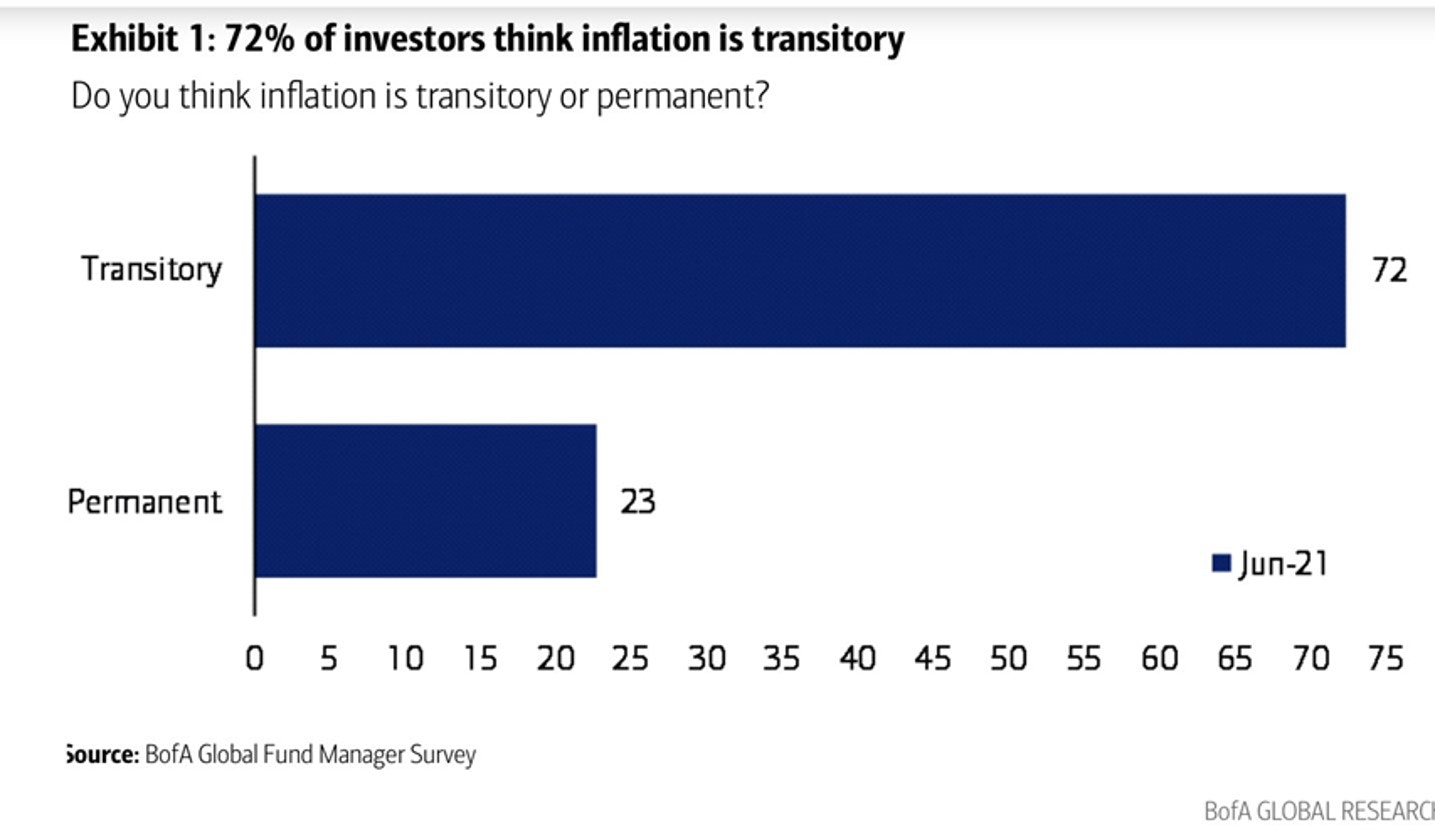

The crowd seems to be falling in line with the Fed’s preferred narrative that inflation will be transitory. A recent Bank of America survey of institutional investors found overwhelming support (72%) for expecting that inflation will be fleeting.

A related question: If the Fed’s on track to start raising rates in a bid to engineer a transitory inflation outcome, is the possibility of a policy error at some point also on the rise? History reminds that central bank decisions tend to go too far, in either direction.

Although the economy is still growing at an unusually strong rate, and more of the same is expected for the rest of the year, perhaps into early 2022, it hasn’t gone unnoticed that the 10-year/2-year yield curve has started to flatten.

The next recession is nowhere on the horizon and the yield curve’s reversal to date after the recent peak is mild and so it’s premature to read too much into the latest changes.

That said, the bond market’s moves over the past two months remind us what questions we should be asking, starting with: How might the economy react if and when the Fed starts raising rates in 2022? What would it take for the Fed to move up the first rate hike to late-2021? How might those answers influence the outlook for inflation?

Lots of questions with little more than speculative answers for now, but the point is that the market’s focused on these and related issues. Meanwhile, the bond market has started penciling in some guesses.