Reporting economic news is a major subject for the media. It starts with the facts, but after lingering briefly, attention turns to speculation about what this means for the boxed-in, painted-in, rock and hard place, corner-bound Fed. Take your pick of the metaphors, including plenty of mixed versions. You’ll hear them all. Probably tomorrow!

The financial world has plenty of self-proclaimed experts in “global macro.” Many of these people never cracked an Econ textbook, and others did not even buy the Cliff notes! In an effort to improve investor understanding, I have added some of these topics to my “blog agenda.”

The employment report is universally regarded as the most important economic release. Employment is of clear importance to the Fed as a measure of economic strength. It is also a key issue in political discourse and public debate. If you consider this at all in your investing decisions, it is vital to have a good understanding of what can be learned from these data.

Here is a key starting point: The more complex the report, the more opportunity for spin.

If you want to be a good consumer of the commentary, here are three things that you need to know but probably don’t.

1. Layoffs tell only half of the story. Everyone watches weekly initial unemployment claims and stories about mass layoffs. What about hiring? We have no good reports about job creation. Many sources have attacked the BLS Birth/Death adjustment. It is so commonplace that it is routinely cited when it adds some jobs — used as a code phrase for fictitious jobs growth.

In fact, the long-term record of the birth death adjustment has been excellent. Each quarter we get an update called the Business Dynamics report. This never makes the news because it is eight months old. That is unfortunate. Unlike the monthly report, it is not an estimate based upon a survey sample, but a collection of data from local unemployment offices. Companies have strong incentives not to overstate employment in these reports.

I use this report to gauge the accuracy of the various monthly estimates. It separates job gains from new establishments from job losses from closing establishments. The BLS monthly report begins with an assumption that “missing data” in the survey, when due to defunct companies, has been offset by new companies. This assumption is far more important than the birth/death model, but the combination has been accurate.

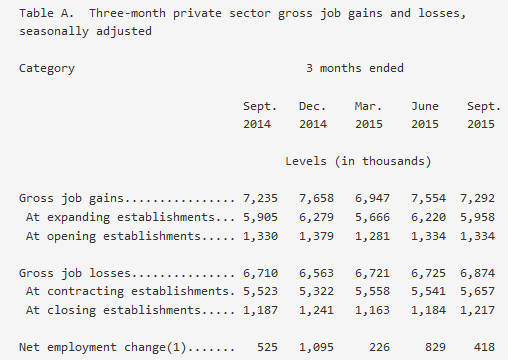

In the latest period for which we have data, here are the gross and net job changes:

A little subtraction shows the net job gain from business births and deaths over the past year is 523K. The b/d adjustment over the same period was 789K. This discrepancy is minor on a monthly basis, or in comparison to the overall number of jobs. I have tracked this for several years, and the differences are usually small and have no consistent bias. Can we finally put this subject to rest?

2. The BLS report is really just an estimate. Many sources also estimate actual monthly net job growth with a variety of approaches. Many of these (changes in state withholding, changes in private payroll reports, changes in national tax revenues) might well be better than that used by the BLS. They basically estimate the size of an elephant each month via a survey. Then they subtract one month from the next.

The sampling error is over 120K, swiftly forgotten or completely ignored in the commentary. This error range is based on an accurate sample with 100% responses. In fact, there are multiple revisions to the original estimate. The margin of error applies to the final revised data, which we will not actually see for many months.

Despite the drawbacks in the BLS approach (and they are skilled statisticians doing a professional job). It is viewed as “official”. In my best post on this subject I explained that others doing estimates were not trying to measure “truth” but instead guess what the BLS would say!

3. Evaluate the overall job changes, not the specific subsets. Most commentators confuse job creation with net job growth. They also give undue emphasis to sub-sector job changes.

Overall job creation is about 2.5 million per month! Job destruction is only a bit lower. Keeping this in mind helps to understand why so many feel the stress of unemployment.

The margin of error for specific subsets is much larger than people realize. I explained this in 2010, but no one ever mentions these facts:

Sampling error means that the businesses or households chosen for the survey (even if all respond) may not accurately represent the actual population characteristic you are trying to measure. If you learn this in a statistics class, you have a jar with a known percentage of black and white marbles from which you draw repeated samples. As you do more samples, you come to realize that they reflect the underlying population on average, but often deviate. There are statistical methods for estimating sampling error. The BLS often cites a 90% confidence interval.

This is understood but usually overlooked in discussing the big headline numbers. For the payroll report, for example, the 90% confidence interval is about 104,000 jobs. Viewed in this way, we could infer that given our survey result actual job growth would be between -4000 and +204,000 about 90% of the time.

When the discussion turns to the various “internals” of these reports, the participants seem to forget that these are are also survey results. Each item has its own 90% confidence interval. Here are some selected examples:

Unemployment rate +/- 0.16%

Size of labor force +/- 490,000

Change in labor force MoM +/- 400,000

Do you see why some of the glib commentary about the unemployment rate and the number dropping out of the labor force might be a bit overstated? It is dangerous to infer too much from monthly changes, even when they seem like large numbers. The errors are actually quite small in proportion to the entire size of the labor force. Source: http://www.bls.gov/opub/ee/empearn201005.pdf (pp. 233-34).

Here are a few more examples:

Average weekly hours +/- 1.65%

Average weekly earnings +/-1.65%

Construction monthly change +/- 24,000

The changes in weekly hours, viewed as such a negative this month, is well within the “noise” level. Last month’s positive reading was only a bit outside the confidence interval. People regularly comment on changes in various subgroup categories when the change is well within the confidence interval. Here is the source for these and other results from the establishment survey.

Conclusion

The monthly employment report is a field day for pundits, but provides little solid information. Understanding the economy requires a longer time period as well as alternative estimates.

- Traders must guess the number (which they could not do even if they knew the “truth”) and also the market reaction. Many think that a strong report will be negative because the Fed will be more likely to nudge rates higher. Sheesh!

- Investors once again have an advantage. The volatility has little to do with the long-term prospects for your positions. You may take what the market is giving you, whether trimming winners or acting on your shopping list.