Perhaps the hardest part of analyzing the eurodollar system is synchronizing all its various dimensions into a common perspective. Coming from the traditional standpoint that views all these various parts as if they are all separate, such a task is often quite difficult. For example, the repo market is almost always described from the cash perspective as if there only exists a supply/demand curve for that side alone. In reality, there is a separate supply/demand curve for collateral that oftentimes overrides any and all cash considerations.

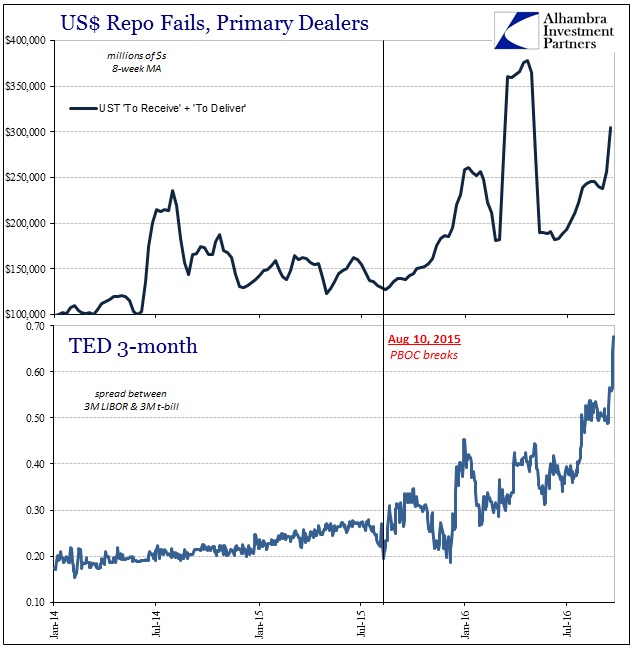

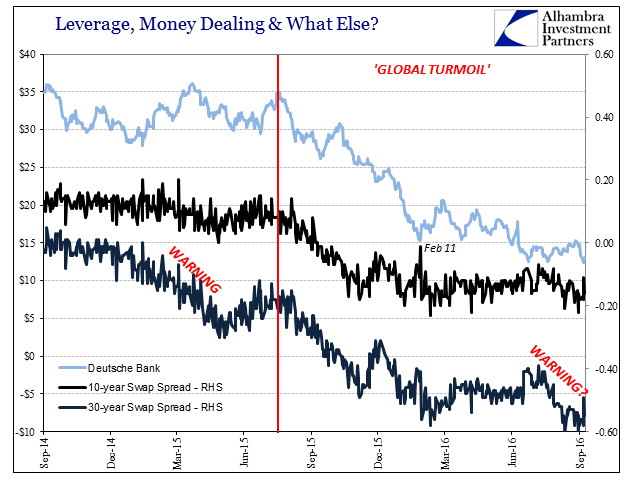

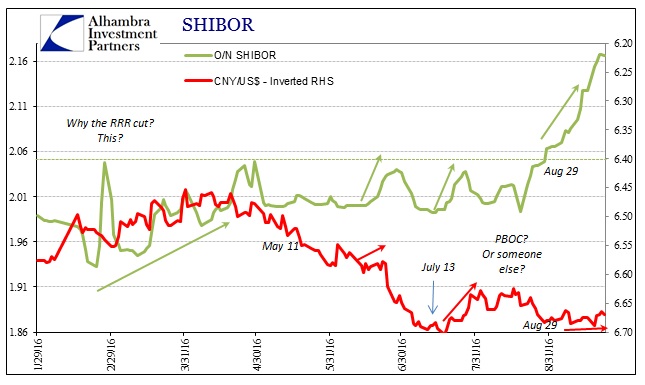

Not only that, mainstream convention rarely puts separate pieces together because from the traditional point of view they don’t seem to belong together. What do negative swap spreads, rising repo fails, and grave Chinese money market distortions all have in common? They are all related evidence of the one thing the media refuses to acknowledge because orthodox economics is treated on faith rather than a scientific basis.

Earlier today, Saudi Arabia announced that it was injecting a massive amount of local liquidity into its banking system. The total program is expected to be around 20 billion riyals in time deposits on behalf of various government sources. There was also an announcement about seven and twenty-eight day repos, but terms for those weren’t disclosed.

The Kingdom’s problem is withdrawal, as in dollars not riyals. The Interbank Offered Rate surged to its highest in seven years last week, as the government prepares to borrow under extraordinary circumstances. The placement of that debt offering is telling; it is to be a $10 billion or so Eurobond flotation. In the mainstream, Saudi Arabia’s problems are pitched as oil prices, and thus quite understandable as being their own.

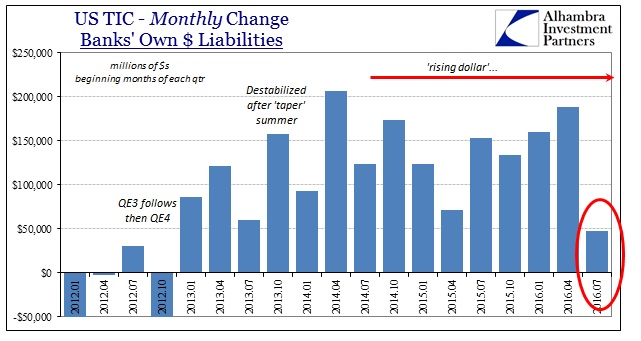

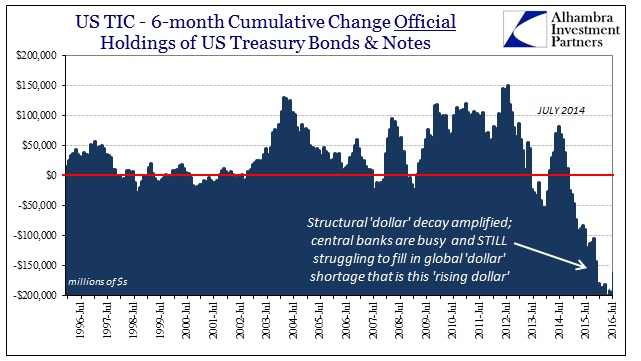

When the TIC figures were updated for July, even the media began to notice that central banks including Saudi Arabia had been selling consistently for some time. In this Bloomberg article, the authors cite this trend as a risk to UST prices as perhaps another sign that “rates have nowhere to go but up”; a cliché that has been constantly deployed since 2011 and has yet to be done so appropriately. Specifically, the piece mentions the Chinese as a primary culprit:

Big holders of Treasuries are selling for a variety of reasons, but they’re all tied to each country’s economic woes. In China, the central bank has been selling U.S. government debt to defend the yuan as slumping growth leads to more capital outflows.

Their Asian neighbor Japan has joined them in the purported selling, though for supposedly different reasons. Back in August, a separate Bloomberg article posited the Japanese and many others who were/are reacting only to negative rates:

Negative interest rates outside the U.S. have caused a surge in demand for dollars and dollar assets, pushing up the cost to get into and out of the greenback at the same exchange rate to levels rarely seen in the past.

This is a variation on the yen carry trade, where it is believed financial institutions borrow at negative or low rates and then invest the proceeds once swapped into dollars in UST’s or other dollar-denominated assets. The Bank of Japan has been, according to this view, supplying some of those dollars via its UST swap window, which looks like “selling UST’s” from the BoJ custody account.

As central banks have been “selling”, it has been left to primary dealers to do the buying. Earlier this year we were told (also in a Bloomberg article) that dealers have been holding much larger inventories of UST’s including bills because those banks are afraid of selling them into the market. To keep prices stable, inventories have risen and remained that way.

Each of these stories in isolation and from the perspective from which they are delivered all seem plausible and unrelated: Saudi Arabia has oil price problems; China is experiencing “capital outflows” because of its own economic circumstances; Japan and Europe have negative rates that increase dollar demand; and primary dealers are doing their patriotic duty so as not to disrupt US government funding.

Like the tumblers on a lock, however, if you turn each perspective around they all lock into place upon a singular circumstance. As I have noted with regard to the Japanese and the dollar, particularly via the basis swap, what starts out seemingly as the carry trade can instead be viewed dollar first, leading to a much different (and consistent) conclusion.

The negative yen basis swap acts like leverage where even yields on the interim “investment” are negative. Any speculator or bank with spare “dollars” could lend them in a yen basis swap meaning an exchange into yen. Because you end up with yen you are forced into some really bad investment choices such as slightly negative 5-year government bonds, but that is just part of the cost of keeping risk on your yen side low. Instead, the real money is made in the basis swap itself since it now trades so highly negative. The very fact of that basis swap spread means a huge premium on spare dollars; which is another way of saying there is a “dollar” shortage.

In the Bloomberg article quoted above describing the Bank of Japan’s “selling UST’s” reaction to it, the same reorientation can be applied:

Japan, the second-biggest foreign holder, has swapped Treasuries for cash and T-bills as prolonged negative rates in the Asian nation pushed up dollar demand at local banks.

Are Japanese banks having difficulties because negative yen rates are driving demand for dollars, or are negative basis swap spreads indicative of FX supply problems for Japanese banks unable to find and obtain “spare dollars?” The latter scenario actually explains further negative rates in yen. In either case, the issue is dollar.

The same can be said of Saudi Arabia, China, and the primary dealers who are not holding bonds as their sacred American duty but hoarding collateral in a repo system that is increasingly unstable. The mainstream is going to great lengths to avoid putting the words “dollar” and “shortage” together because orthodox ideology means that cannot possibly be the case. Therefore, every financial problem around the world that can be otherwise easily distilled by just recognizing the “dollar shortage” is instead chopped up and isolated as if individual anomalies of idiosyncratic circumstances.

In other words, it is supposed to be just cosmic coincidence that the world has issues all involving the “dollar” because each instance can plausibly (if only on the surface) be viewed in different ways that accidentally lead to that conclusion. Recognizing the “dollar” for what it actually is and how it connects all these seemingly disparate circumstances dissolves the fog of confusion about what is actually going on not just in money and global liquidity but also the real economy. The world has a big “dollar” problem, not an unending string of smaller individual problems that just so happen to all involve dollar funding.