US inflation was low before the pandemic started and as the nation heads into what’s shaping up to be a rough winter of resurgent Covid-19 the odds appear low for higher pricing pressure in the near term. But as investors, economists and policy makers consider life on the other side of the coronavirus crisis, contemplating the possibility of firmer inflation is gaining traction as a forecasting exercise.

The Wall Street Journal this week provocatively wrote that “Inflation could be poised for a comeback, explaining that:

“some economists are starting to embrace the idea that a prospective Covid-19 vaccine could allow people to once again spend money on travel, restaurants and other services—and drive up prices in the US.”

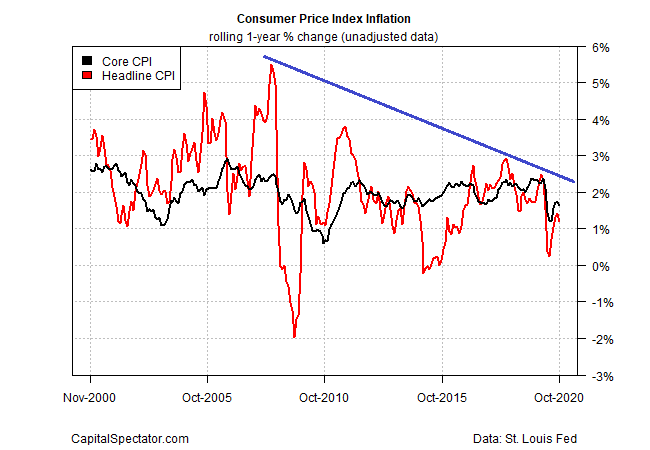

I say “provocatively” because the official inflation numbers to date betray no hint of an upside breakout from the downside trend of recent years. The year-over-year change in the Consumer Price Index through October, for instance, suggests that inflationary pressure remains muted.

But pent-up demand, once fully unleashed at some point, could be a game-changer for inflation, some analysts predict. Jim Bianco of Bianco Research advises that “the market is starting to see a Fed hike on the distant horizon. This is how a shift in thinking begins. The driving reason for this change seems to be a resurgence of inflation over booming real growth.”

The reduction in supply overall, due to the pandemic, combined with a rising population and “unprecedented” government-financed demand stimulus, which has unleashed a surge in government deficit spending, will conspire to stoke inflationary momentum, he anticipates. Bianco writes:

“Huge deficits mean huge spending. Huge spending bids prices higher, otherwise known as inflation.”

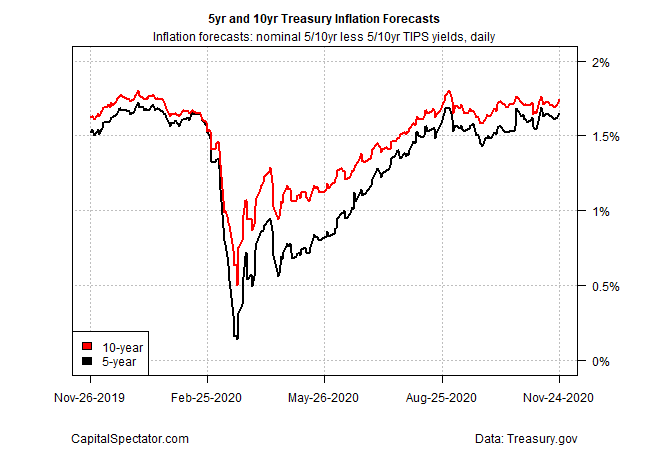

The Treasury market has certainly revised its inflation outlook to the upside in recent months, albeit after dramatically cutting the implied forecast during the early days of the pandemic. But while the yield spread for nominal les inflation-indexed Treasuries has been unusually volatile lately, the current gap is roughly at the level that prevailed before Covid-19 first roiled markets in March—roughly 1.7%.

If and when the Treasury market’s implied inflation forecast rises further, a more concrete sign of pricing-pressure risk will emerge. An increase above 2% would certainly grab the crowd’s attention. But for the moment, this indicator appears more inclined to move sideways.

That could change, of course, if the economy recovers at a stronger-than-expected rate—a possibility that Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs, says is a possibility next year once warmer weather and vaccine distribution rolls out.

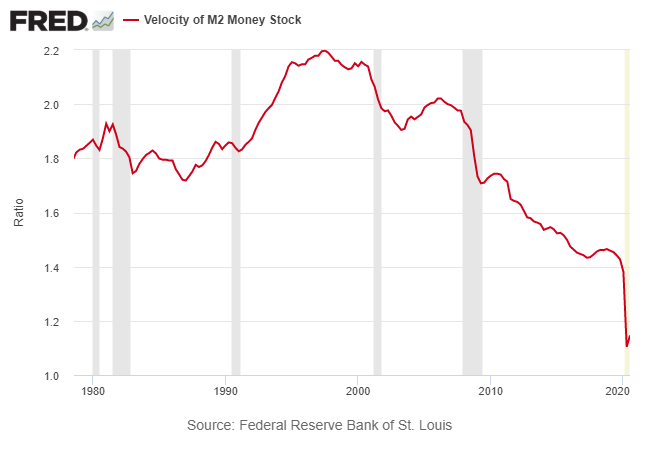

The bigger question is whether the factors noted above will be strong enough to overcome the secular forces that have been driving inflation lower for several decades? The aging of the population (and the related propensity to save rather than spend) and the rising use of technology, for example, have been key drivers of lower-for-longer inflation and it’s not obvious that these trends are set to fade anytime soon. Perhaps that explains why the disinflationary bias via the decline and fall of the velocity of money persists.

For now, inflation risk remains low. But next year could bring a major test. If and when expectations change, an early shift will be reflected in Treasury yields. A gently reviving 10-year/3-month Treasury yield curve hints at the possibility that the early stages of regime shift may be unfolding, although here too the recent rise only revives the spread to the level of late-2018—hardly a period of raging inflation risk.

Nonetheless, the upside pressure for inflation may be increasing, which begs the question: If a post-coronavirus economic recovery in 2021, fueled by a vaccine rollout, doesn’t materially lift inflation, what will?