There has been some recent buzz about the economic performance in Spain. Bloomberg reported that Spain posted its best quarterly performance in eight years and June home sales was up 14%, which was the best performance since March 2014.

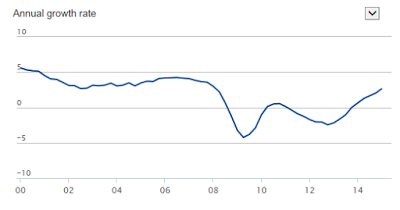

Indeed, Euro area statistics show that Spanish GDP growth has improved considerably.

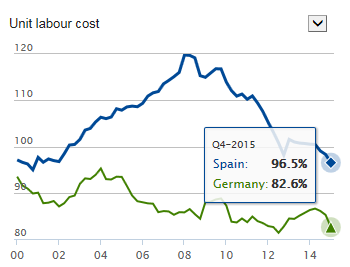

Unit labor costs have nosedived since 2008 and Spain is becoming more competitive.

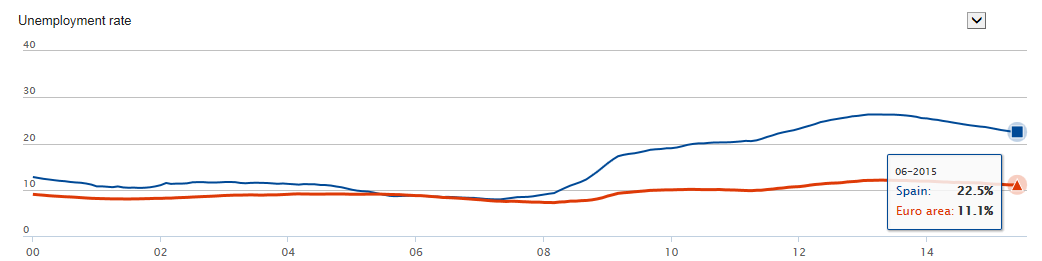

The unemployment rate has begun to improve, though it remains painfully high compared to the rest of the eurozone.

FT Alphaville documented the export revival in Spain:

One example of this is cars and trucks. Spain has long been the second-biggest manufacturer of vehicles in Europe. (The plants are all owned by the major German, Japanese, American, Korean, and French labels, but the cars are made in Spain.) However, the trade surplus has increased since the crisis.

At the 2007 peak, Spain made around 2.9 million cars. Now it makes closer to 2.6 million. Meanwhile, domestic car sales collapsed from about 1.6 million before the bubble to around 900,000 now, although Spanish new car registrations are now growing by more than 20 percent annually. More than 80 percent of the cars currently made in Spain are exported elsewhere.

In addition, the country is undergoing a productivity boom as the financial excesses of the last cycle have been repaired (emphasis added):

At the peak in the middle of 2008, Spanish banks were sending about 3.4 per cent of Spain’s GDP to foreigners. Now they send less than 1 per cent. Meanwhile, Spain’s banks still receive almost as much income from abroad, as a share of GDP, as they did before. The overall difference between payments to foreign holders of Spanish assets and income received by Spanish holders of foreign assets has shrunk by about 2 percentage points of GDP between the start of 2009 and the end of 2014.

The last point we want to highlight is that, despite the extensive deleveraging in the aggregate, particularly among Spanish businesses, the most productive and export-oriented firms actually increased their borrowing to expand capacity and invest in domestic production. This could help explain the post-crisis Spanish productivity boom.

Researchers at the Banco de Espana have found that the businesses which were relatively less indebted going into the crisis generally had better sales and profit growth since then. Importantly, these firms took advantage of changing economic circumstances by borrowing to boost capacity and hire more workers. By contrast, the businesses that borrowed during the boom generally had falling sales, and had to respond by firing workers, cutting investment, and repaying their debts. (This is sort of similar to what other economists studying the US have found.)

A triumph of the Grand Plan

In a past post (Mario Draghi reveals the Grand Plan), I wrote about how the European elites planned to fix Europe. The ECB would do its best to hold things together with monetary policy, which bought time for member states to reform. By "reform" I mean a variety of macro and micro-economic solutions (see Draghi`s 2012 WSJ interview for details):

- Macro solutions like "good" austerity, in the form of lower taxes and lower government expenditures

- Micro solutions in the form of structural reform, whose objective is to get rid of the "jobs for life" idea. That means labor market reforms to eliminate job security and improve market conditions to encourage business formation as a means of fighting the problem of youth unemployment because their elders had "jobs for life".

A recent Bloomberg View article outlined and applauded the Rajoy government`s efforts in these areas. First, there was the macro leg of government austerity:

The government of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy bowed to austerity demands, cut public-sector wages and benefits, and increased VAT to 21 percent (with exemptions) from 18 percent. Had he stopped there, Spain might have bumped along the bottom for a good while longer, rather than seeing the recovery it's now enjoying.

The second and equally important part was the micro-economic solutions of structural reform:

But Spain's recovery today also owes a lot to hard reform aimed at particular failings in the economy. The Rajoy government braved street protests and the rise of an anti-reform left-wing opposition and persisted in a deliberate rewiring of the Spanish economy, with an emphasis on far-reaching labor-market and tax reforms.In 2014, the government said it would gradually lower the corporate tax rate to 25 percent from 30 percent. The top marginal rate on personal income will fall to 45 percent from 52 percent. The government is limiting deductions, broadening the tax base and making a serious effort to curb evasion.

Companies have been given more flexibility to set wages and working conditions. Wage growth that had run ahead of productivity has moderated. The barriers that created Spain's notorious two-tier labor market, with its underclass of workers on temporary contracts, have begun to fall.

The draconian approaches began to pay off, though there was an element of luck involved.

Low inflation, a cheap euro, the fall in energy prices and renewed financial stability in Europe have supported consumer spending and lifted Spain's beleaguered retailers. Holidaymakers have favored Spain this season, too -- in part because visiting Greece without bundles of cash has presented difficulties. Put much of all that down to luck.

The price paid

To be sure, these gains were not without costs. FT Alphaville lamented that it is taking a decade or more for Spain to return to normalcy (emphasis added):

Spain seems to have done everything right — within the constraints imposed by membership in the euro area and the European Union more generally. Debt is down, reliance on foreign capital is down, exports and productivity are up. And the economy is, finally, growing at a brisk clip. The government is planning on cutting corporate taxes to boost investment and using some of the windfall from faster growth to lower personal income taxes, which ought to help households.Yet for all the recent progress, Spanish unemployment remains tragically high. Anything resembling a healthy economy is still years away.

What else could Spain have done? What else can it reasonably be expected to do?

It doesn’t bode well for the future of the single currency if the country that followed the policy recommendations of Europe’s leaders most closely, and which embraced some of the best economic governance on the continent, requires a decade or more to return to normalcy after a crisis.

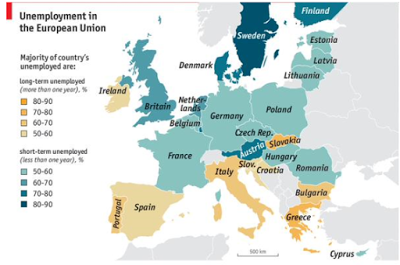

Moreover, long-term unemployment remains stubbornly high (via Ian Bremmer):

I recently wrote that Greece and the Eurogroup were talking past each other (see Greece: How both sides are right AND wrong). The Greek government was speaking the language of macro-economics while the Eurogroup was speaking the language of micro-economic adjustment. The ongoing discussions over Greece has become a European tragedy.

I also wrote that if the Tsipras government were to truly embrace and "own" the micro-economic structural reforms asked of them by the creditors, then Greece could see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Spain has done all those things. Their situation is improving, but the experience shows that the path is not easy, the task is not finished and Spaniards are still paying for those reforms. The Spanish experience raises a number of important questions about the European Grand Plan:

- Does the Spanish experience vindicate the European Grand Plan?

- Or is this a case of changing a light bulb by holding the light bulb and then moving the house around it?

- Can this approach be characterized not as a bug, but a feature of a currency union without a political union?

Here is the most important question of all:

- What lesson should Greece or any country contemplating joining the euro take away from this?