Investing.com’s stocks of the week

Back in June 2019 (exactly one year ago) – I published an article highlighting the increasing fragility in the corporate credit markets. To give you some context: I wrote about the towering wall of ‘triple-B’ (BBB) rated corporate debt that was nearing a ‘tipping-point’. And how fragile corporate debt markets really were.

(Note that the BBB-rating is the last notch on the investment grade level—thus anything lower is considered ‘speculative’—aka junk. These are known as ‘fallen angels’).

So – one year later – how are things since then?

Well – not only are things much worse now (thanks to both the 2019 global recession and 2020 COVID-pandemic). But there’s significantly more ‘fallen angels’ today than there were just a few months ago, as-well as a record number of firms at risk of becoming junk-rated.

Let me explain. . .

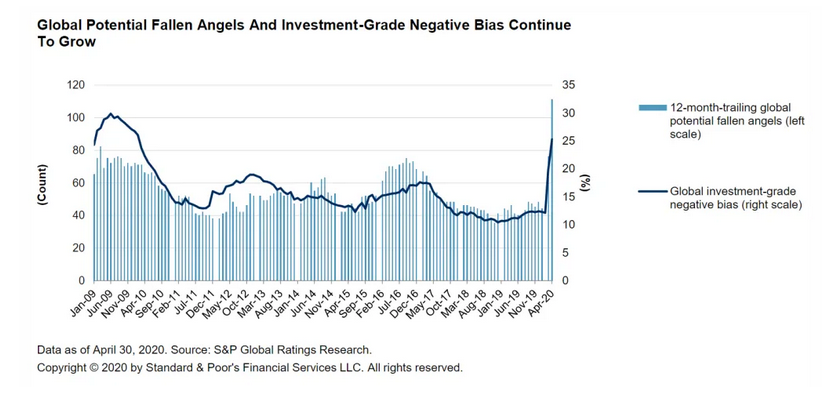

According to a recent S&P Global report—there are so far 24 new fallen angels worldwide in 2020 (the most since the 2015-16 slowdown). But—most importantly—there’s now a record-high 111 ‘potential’ fallen angels (meaning: a wave of corporations that are one-step away from getting downgraded to junk).

And to make matters worse, the ‘negative bias’ (aka the percentage of debtors with a negative outlook for all investment grade firms) recently reached 25%, the highest level since the 2008 financial crisis.

Just take a look at the chart below:

Thus, you can see how very fragile credit markets have become over the last few months.

But that’s not all.

Because the momentum (aka the rate of change – RoC) is still to the downside. . .

(Remember: the rate of change is key for speculators as it mathematically measures the percentage change in a value over a certain period of time. Putting it simply, the larger the percentage the greater the momentum. And just as contrarian investor Keith McCullough, CEO at Hedgeye, says: “absolutes don’t matter. It’s the rate of change that does”.

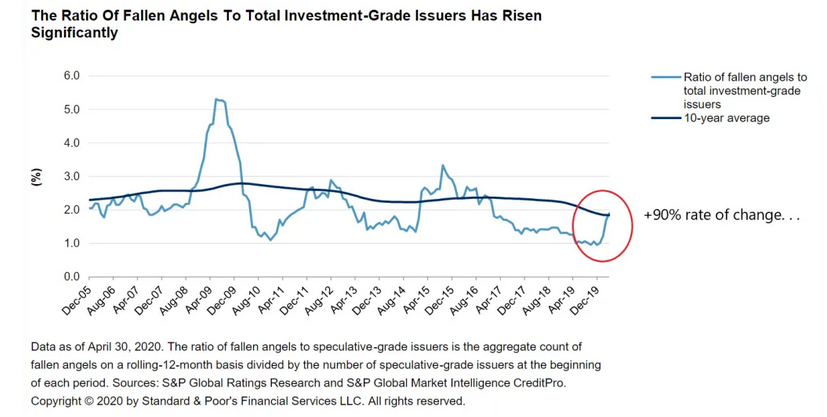

Putting this into perspective: take a look at the ratio of fallen-angel-firms-to-total-investment-grade-issuers over the last 15-years. . .

Not only has the ratio of fallen angels already surpassed its 10-year trailing average within just the last five-months, but we’ve seen a 90% increase in the rate of change for new fallen angels (i.e. 1% in Dec/2019 to 1.9% in Apr/2020 equals a 90% increase).

(Note that this is a sharp increase—especially in such a short period of time.)

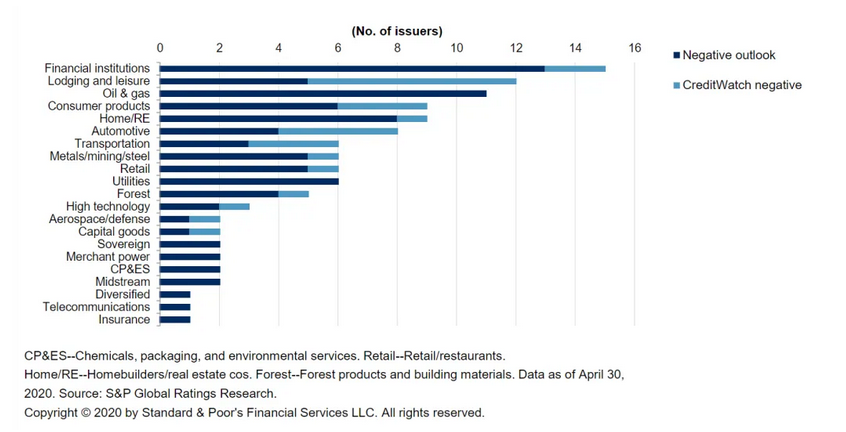

And considering that a record 26 of the 111 firms (most being financial, hotel, oil/gas, and auto firms) have a negative ‘CreditWatch rating’ (i.e. a risk of downgrade in less than 90-days)—there’s a strong chance that this ratio will climb significantly higher over the next 12-months.

And to make matters worse, there’s roughly $10-trillion in dollar-denominated corporate debt worldwide that’s maturing over the next 42 months. With peak maturities hitting in 2022 (just a little more than a year from now).(And there’s $1.2 trillion of this debt maturing from junk-rated U.S. firms – aka fallen angels – that will desperately need funding.)

This means many of these firms must either repay creditors the full amount owed with cash on hand. Or roll-over (aka refinance) their existing debts (meaning: they’ll need take out new debts to repay old debts).

But—since most of these firms are near-junk already—I’ll bet most won’t have the cash available to repay their creditors. Thus needing to borrow more.

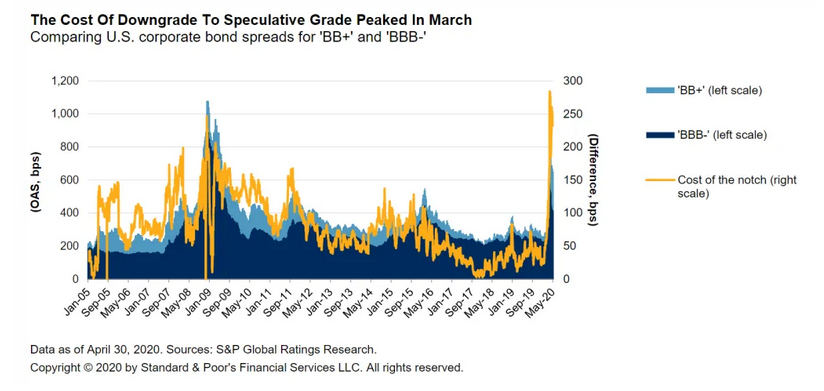

And therein lies the problem: the cost for junk-rated firms to borrow is significantly higher than historic averages. For instance, just take a look at the current difference in spreads between U.S. corporate debt rated BBB- (the bottom notch for IG) and BB+ (the highest notch for junk).

It’s more than 270 basis points (2.70%)—the highest it’s been since 2008:

This indicates significant risk-aversion in the bond market (aka investors are nervous), leading to much wider bond spreads. (Indicating investors want higher yields for the additional risk.)

This makes it costlier for lower-rated firms to borrow—which amplifies the risk of default. And risks creating an ‘iliquidity-pocket’ in the sector (aka cause liquidity to dry up as investors flee entirely).

(Keep in mind that many institutional investors, such as pension funds, insurance firms, some mutual funds, etc, can’t legally own anything other than investment grade debt. Meaning: money managers will quickly dump these holdings—leading to a further drop in junk bond prices; further accelerating the downside).

And all this happening at a time when global economic growth is extremely weak. Thus, corporations (especially the near-junk-rated kind) are more fragile than they’ve been in the last 15 years. And going forward speculators should expect a possible wave of defaults and downgrades.

Or—putting it another way—there’s a high chance for a black swan to show up in the corporate credit market.

So, in summary, the record number of potential fallen angels has put bond holders (including insurance firms, pensions, and investment funds) in a fragile position. Especially as both economic conditions and corporate earnings continue to under-perform.

Putting it simply, the bond market’s at great risk of choking on all these potential fallen angels. So don’t be surprised if it eventually does.

I sure won’t.

P.S. No wonder the Federal Reserve began buying both BBB-rated and junk-rated debt in late-May 2020 for the first time ever. There are just far too many companies at the margin of being downgraded—which would likely cripple lending markets. Thus expect the Fed to ramp up their junk-bond buying with more printed money in the future.