“There’s already great speculation about the exact timing of the first rate hike and this decision is becoming more balanced. It could happen sooner than markets currently expect…

…The need for internal balance – to use up wasteful spare capacity while achieving the inflation target – will likely require gradual and limited interest rate increases as the expansion progresses. The start of that journey is coming nearer.” – Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, Lord Mayor’s Banquet for Bankers and Merchants of the City of London at the Mansion House in London on June 12, 2014.

That journey has yet to get started.

A little over three years ago, the Bank of England prepared financial markets for an imminent tightening cycle for monetary policy. The British pound (NYSE:FXB) responded to Carney’s speech at that time by racing higher for about a month. GBP/USD reached a post-recession high…and then it fell nearly straight down for the next NINE months. It took another 18 months and much greater declines for the pound to reach a sustained bottom. Such was the grave error in judgement that the Bank of England made in claiming that it would launch a more aggressive tightening cycle than the market expected in 2014. While I did not anticipate such a grand miss, I did express my skepticism. I claimed that the market moved too fast to accept the Bank of England’s claims.

Fast forward to September 13, 2017. The Bank of England eventually had to back off its hawkishness. Last year’s Brexit vote forced the BoE to deliver a rate cut. Now the itch is back: Mark Carney and the Bank of England last week scolded the market for under-appreciating the upside risks to interest rates in its latest statement on monetary policy:

“All MPC members continue to judge that, if the economy follows a path broadly consistent with the August Inflation Report central projection, then monetary policy could need to be tightened by a somewhat greater extent over the forecast period than current market expectations.”

“Somewhat” sounds minor, but the currency market reacted in a major way. The pound soared. Across the board, sterling currency pairs stretched well beyond Bollinger Bands (BB). GBP/USD broke out above the intraday low that immediately followed Brexit and hit a fresh 15-month high.

The buying pressure in the pound helped push GBP/USD well beyond its upper-Bollinger Band (BB) for two days. This week started with a significant cooling period.

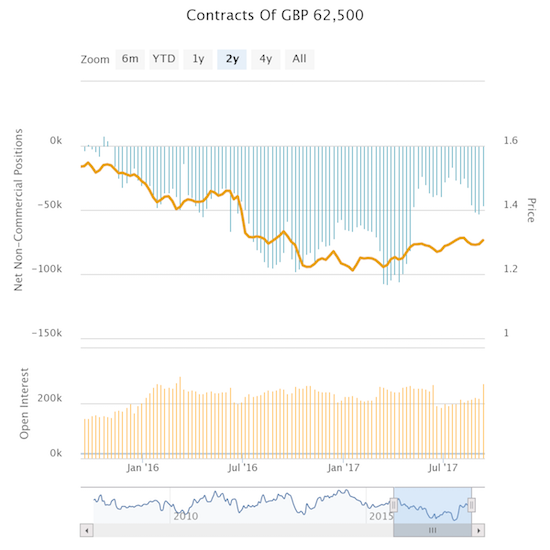

I understand why the reaction was so sharp and sustained. Even though strong inflation data ahead of the monetary policy meeting woke up the buyers, speculators went into the BoE meeting with freshly rebuilt net short positions. I was also caught flat-footed with a net short position that was larger than I should have held given the early technical warnings (granted a large pullback in the pound going into the meeting fooled me into thinking I was likely leaning the right way!).

Caught by surprise: speculators recently rebuilt short positions against the British pound.

Despite the BoE’s warning, I once again find myself skeptical of the Bank of England’s plans. I find reason to be skeptical in the transcript of the monetary policy meeting (which includes the statement).

Firstly, back in August, the BoE warned the market that it was underpricing the upside risk for rates (emphasis mine):

“The Committee judges that, given the assumptions underlying its projections, including the closure of drawdown period of the TFS and the recent prudential decisions of the FPC and PRA, some tightening of monetary policy would be required in order to achieve a sustainable return of inflation to target.

Specifically, if the economy follows a path broadly consistent with the August central projection, then monetary policy could need to be tightened by a somewhat greater extent over the forecast period than the path implied by the yield curve underlying those projections. Any increases in Bank Rate would be expected to be at a gradual pace and to a limited extent.”

The currency market’s response? The earlier chart above shows that the pound sold off for three weeks before finding a sustained low. The market oozed with skepticism and/or nonchalance.

The BoE reflected on its earlier warning:

“The Committee had noted at its last meeting that, if the economy were to follow a path broadly consistent with the August Inflation Report central projection, then monetary policy could need to be tightened by a somewhat greater extent over the forecast than the path implied by the yield curve underlying the August Report. Since then, the economic data had been broadly in line with those projections. If anything, recent developments had suggested that the remaining spare capacity in the economy was being absorbed a little more rapidly than had been expected, and that inflation remained likely to overshoot the 2% target over the next three years.”

In this statement alone the BoE seems to want things both ways. The Bank congratulates itself for economic data that followed projections. Yet one specific part of the economic data – spare capacity – changed enough to warrant an adjusted warning to the market.

Moreover, nothing in aggregate dramatically changed since the August Inflation Report. The BoE references a “slightly stronger picture than anticipated” and couched all of its language in the cloak of uncertainty and caveats.

“Since the August Report, the relatively limited news on activity points, if anything, to a slightly stronger picture than anticipated…

Approached from the expenditure side, the Committee judged that most early indicators were consistent with a somewhat stronger profile for consumption growth in Q3 than the 0.2% rate that had been incorporated into the Inflation Report. That could potentially also suggest an upside risk to GDP growth.”

Despite the upside risk to GDP growth, the BoE pointed out recent weakness in GDP growth when calling out better than expected unemployment readings.

“In contrast to the recent weakness of GDP growth, employment growth had been resilient. As a result, the unemployment rate had fallen to 4.3%, its lowest in over 40 years and a little lower than forecast in August.”

The BoE did note the recent higher than expected inflation readings but found reassurance in the well-anchored inflation expectations of UK households.

“Twelve-month CPI inflation had risen to 2.9% in August, 0.2 percentage points higher than had been expected in the Committee’s latest Inflation Report projections. The twelve-month change in CPI excluding food, alcohol, tobacco and energy had increased to 2.7%, also 0.2 percentage points above expectations and the highest core rate in over five years. More generally since the Committee’s last meeting, developments in the oil market suggested greater near-term upward pressure on inflation from petrol prices. Twelve-month CPI inflation was now likely to rise to above 3% in October. The latest household indicators had, nevertheless, suggested that inflation expectations had remained well anchored.”

Compare the new 12-month CPI expectation to the previous one from the August Inflation Report: “The MPC expects inflation to peak around 3% in October and to remain around 2¾% until early next year.” Peaking around can easily be interpreted as consistent with “rising above.” Indeed, I assume the two remain roughly equivalent because the BoE was essentially very careful to avoid explicitly boosting its own inflation expectations and forecast. Instead, the BoE lowered its “tolerance level” for above-target inflation. This tolerance is a softer version of inflation targeting and of course can change on a dime depending upon incoming economic information.

“Recent developments suggest that remaining spare capacity in the economy is being absorbed a little more rapidly than expected at the time of the August Report, and that inflation remains likely to overshoot the 2% target over the next three years….

As slack had continued to erode, this lessened the trade-off that the MPC was required to balance and, all else equal, reduced the MPC’s tolerance of above-target inflation.”

The next rate hike remains far enough in the distance that the Bank of England can continue to string markets along while attempting to talk the currency higher. A higher sterling is important to anchoring inflation because, in the August Inflation Report, the BoE claimed that a depreciated currency was to blame for the hot levels of inflation:

“Conditional on the current market curve, which implies that Bank Rate will rise by ½ percentage point over the next three years, inflation is projected to remain a little above the target at the end of the forecast period – an overshoot that reflects entirely the effects of the referendum-related fall in sterling.”

The BoE now observes the following:

“The first 25 basis point rise in Bank Rate was not fully priced in by financial markets until the second half of 2018. The majority of economists responding to a survey by Reuters had expected Bank Rate to remain at 0.25% until at least the end of 2018.”

This assessment means that the BoE can continue to TALK about hiking rates for many more months to come without doing anything. Such a delay of course increases greatly the odds that the Bank will find new reasons to back down on its hawkishness yet again.

Regardless, note well that over the next three years, the expectations remain that the BoE has just one rate hike in its pocket. Carney and crew just flagged to the market that it is supposedly willing to take its shot earlier than the market previously expected. I will be interested to see just how much higher the market thinks sterling needs to get to price in one rate hike in the earlier part of the next three years…and then the reasonable risk that the BoE will find itself needing to talk the currency back down again. I will trade accordingly!