With the focus on the upcoming Greek election and the growing realization that all is not well in Spain, the markets have paid far too little attention to the euro zone’s most important player: Germany. While the world has marveled at Germany’s economic resilience, it would be naïve to believe it can indefinitely resist both the economic turmoil that has gripped so many of its fellow European countries and the slowdown in the emerging world.

The situation is also looking tough for Germany on the geopolitical front. It is facing both growing pressure to relax the austerity measures it has imposed on countries and growing calls to provide further financial aid to the euro zone just as opposition to these measures from the German public is mounting. This deadlock is leading to increasing tensions between Germany and other euro zone countries. A weakening German economy would only strengthen public opposition to further financial assistance. A Germany that is both facing a darkening economic outlook and increasingly feeling threatened by seemingly never-ending demands for more funds to fight the debt crisis would significantly add to the already formidable risks facing the euro zone.

In this report, we will look at some of the key challenges and risks facing Germany and their potential impact on the euro zone debt crisis:

• Growing doubts over the ability of Germany’s economy to continue resisting the impact of the debt crisis

• A growing resentment of its success by struggling euro zone countries

• Mounting tensions between Europe and other euro zone countries

• The German government’s increasing political vulnerability

• The political and economic risks of a Greek collapse

As Strong As It May Be, Germany’s Economy Is Not Immune To The Recession In Europe And Slowdown In China

To date, Germany’s economy has escaped relatively unscathed by the debt crisis that has gripped much of the euro zone. Its economy grew by 3% in 2011, and by 2.1% on an annualized basis in the first quarter of 2012. The OECD projects Germany's economy will grow by 1.2% this year and by 2.0% in 2013, making Germany one of the best performing advanced industrial economies in the world.

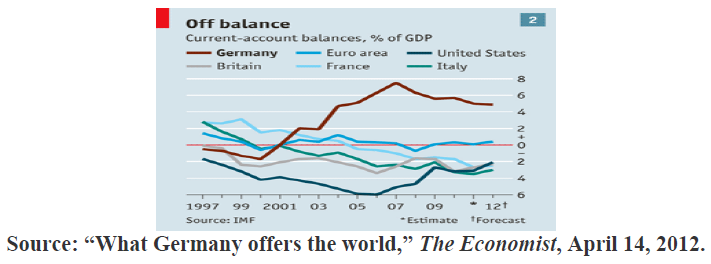

Germany relies heavily on its exports to power growth. Exports account for 40% of Germany’s GDP, versus 30% for China and only 15% for the United States.Moreover, in aggregate terms, it is the world’s third largest exporter, behind China and the United States.Germany is a particularly large exporter of machines and chemicals, which account for about half of its exports.

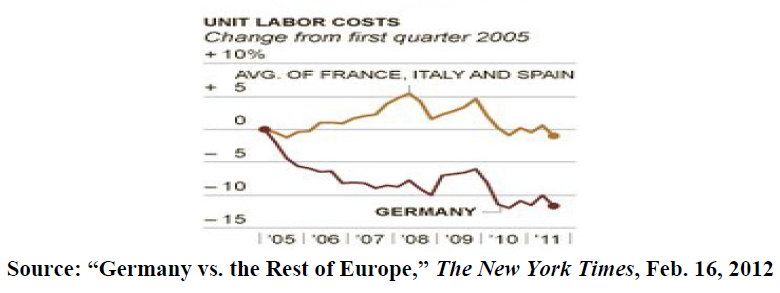

In addition to a skilled workforce, the competitiveness of Germany’s manufacturing sector has been significantly boosted by the labour reforms undertaken in the 90s in which workers agreed to show more flexibility on wage levels and hours worked in exchange for increased job security.

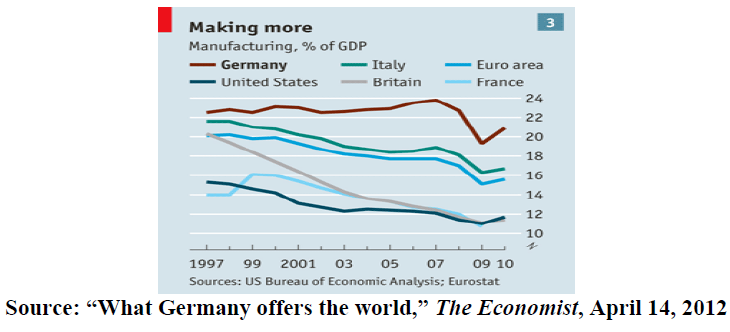

As a result, the manufacturing sector plays a much larger role in Germany’s economy than it does in most other developed countries.

Thanks to cheap borrowing costs, relatively low household debt levels and unemployment of only 6% (versus close to 11% for the euro zone), domestic consumption has also held up well.

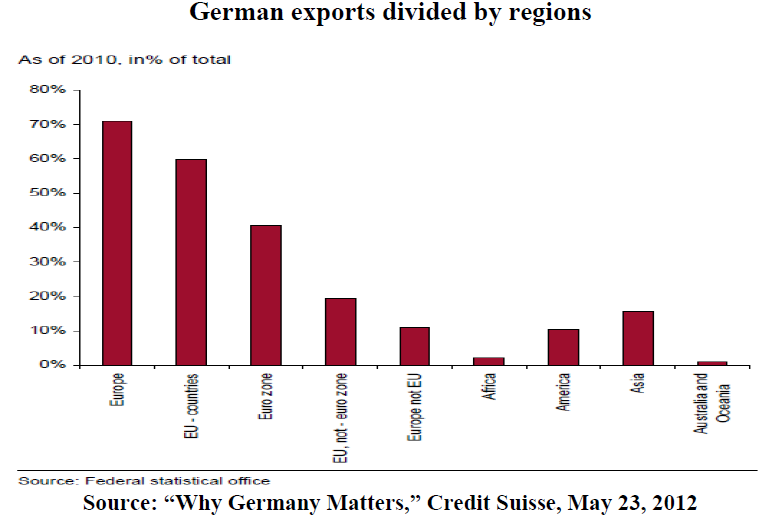

The main factor behind Germany’s strong export performance is growing demand from outside the European Union (EU). In fact, exports to non-EU countries increased by 11.2% in the first quarter, versus only 2.3% for the EU.The export of high-end products, such as luxury cars, to Asia has been particularly strong.However, it is important to keep in mind that the lion’s share of Germany’s exports still goes towards Europe. More than 70% of Germany’s exports go to other European nations, while 40% go to fellow euro zone members. This is in comparison to under 20% for Asia.This dependence on European markets means that the longer Europe struggles economically, the greater the risk Germany’s economy will be negatively impacted. Complicating matters further, the Chinese economy, its largest Asian export market by far, is slowing down as well.

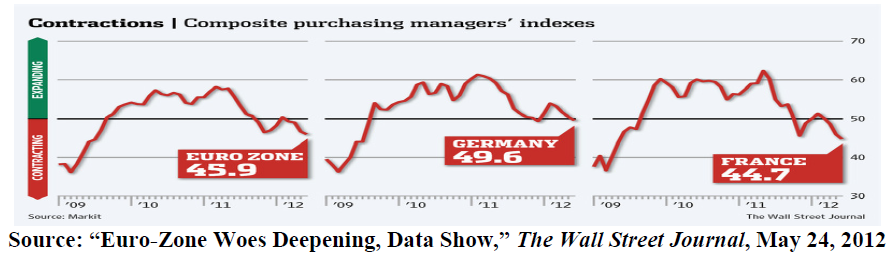

Indeed, recent data from Europe’s purchasing manager’s index indicates that Germany’s resistance to the crisis could be wearing thin. The index, which includes manufacturing and services, shows that Germany activity hit a six-month low in May. A reading below 50 signals contraction.

Resentment Toward Germany’s Economic Success On The Rise In The Euro Zone

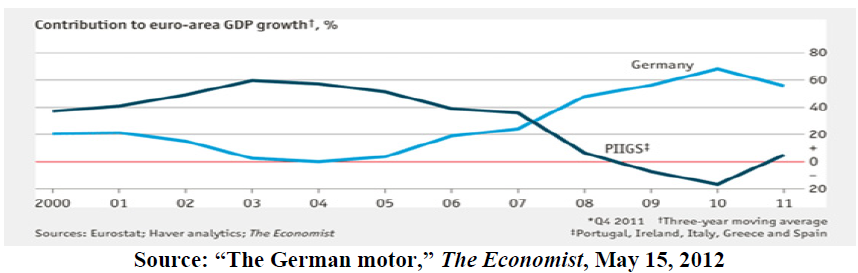

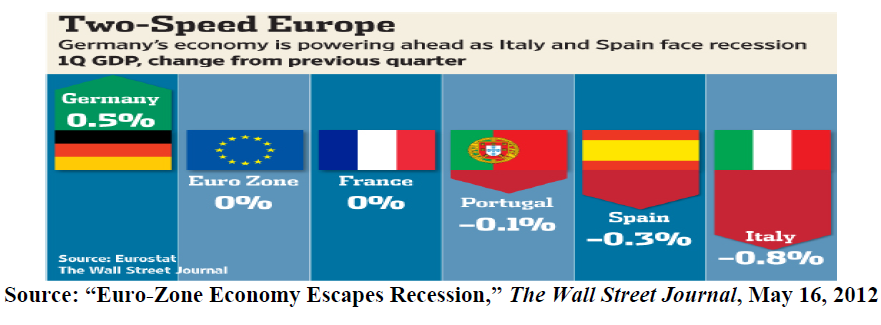

Without Germany, the euro zone’s economy would have declined by about 0.2% for the first quarter of 2012.Indeed, despite only accounting for about 30% of the euro zone’s GDP,from 2007 to the first quarter of 2012, Germany has been responsible for 65% of its growth.

Yet, just as income inequality often creates socio-economic tensions within a country, Germany’s flourishing economy is creating tensions within the euro zone.

In stark contrast to Germany’s strong performance for the first quarter of 2012, most other key economies fared poorly. France’s economy posted zero growth, Italy’s and the Netherland’s contracted for the third straight quarter, and Spain’s economy fell for the second quarter in a row. Out of the euro zone’s 17 members, seven are in a recession (Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Portugal and Slovenia). Several eastern European countries are also facing growing economic difficulties, with the economies of Romania, Czech Republic and Hungary all contracting

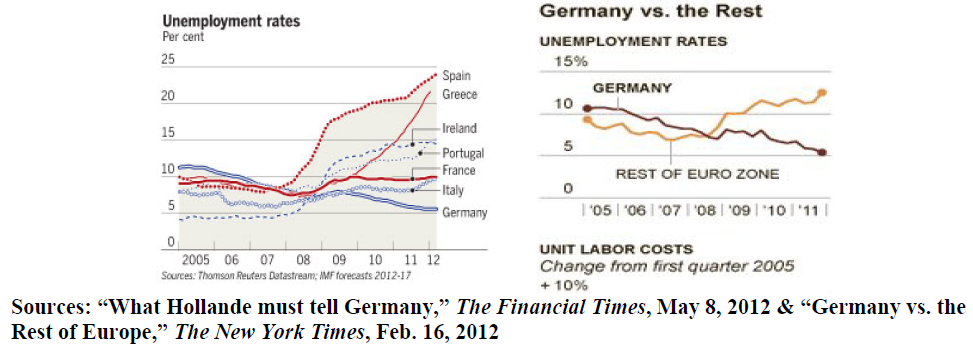

Another sign of the widening economic divide between Germany and much of the rest of euro zone can be seen in the unemployment rates.

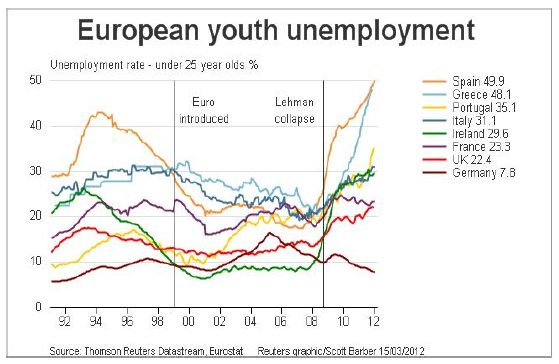

The contrast is even starker when it comes to youth unemployment.

The backlash against Germany’s success has even led to accusations it is capitalizing on the economic difficulties of other countries. This stems from the fact that the economic difficulties of several euro zone countries has held down the value of the euro, which in turn has made German exports more competitive in global markets. Indeed, if the euro were to collapse, a re-introduced deutsche mark would no doubt eventually rise in value against many other currencies, thus making Germany’s exports less competitive. Germany has even been blamed of deliberately locking other countries into an unfavourable exchange rate. For example, there have been reports that some Italian companies are muttering about a German conspiracy to devastate Italian companies in order to steal market share.

Before the formation of the euro zone, European countries would often resort to currency devaluation to compete with their German counterparts. While this action was widely criticized as an unfair trading practice, it did allow these countries to compete with Germany and kept anti-German sentiment to a minimum.

Is The Solution For Germany To Become Less Competitive?

Some economists feel that one way to improve the outlook for the euro zone, and reduce tensions between Germany and other countries, would be for Germany to encourage a general increase in the wages of its workers. This in turn would make it easier for companies based in the most troubled countries to compete with their German counterparts. The problem is that while asking Germany to reduce its trade surplus makes sense in theory, winning support for this strategy from its business sector would be very difficult.

If Germany were to intentionally undertake measures to erode the hard-won competitiveness of its all important export sector vis-à-vis the United States, China and other emerging market countries, there would certainly be a political backlash by German business leaders, not to mention inevitable job losses for German workers. The president of the Bundesbank, the German central bank, flatly rejected calls for the bank to let inflation (and wages) rise significantly in order to rebalance growth in Europe.

Another tension point is that the strict bailout conditions Germany imposes in return for financial aid is causing political and economic turmoil in the debtor countries. Nonetheless, a recent poll found that 83% of Germans feel bailout funds should continue to be disbursed only under the most stringent conditions. This means any significant change from her tough prescription for Europe’s debt problems would hurt Merkel’s standing in the polls and even risk a revolt from within her own party.

Germany’s resistance to the idea of eurobonds, which is being strongly pushed by Italy and France, is a perfect case in point. The German government and citizens are strongly opposed to being liable for the spending decisions of other countries. They feel going this route would not only reduce the pressure on heavily indebted countries to make deep budget cuts, but also increase Germany’s already significant financial exposure to Europe’s most troubled countries. Germany is on the hook for 211 billion euros of the bailout fund, making it by far the largest contributor. This does not include the potential costs of recapitalizing the European Central Bank (ECB). The Chancellor recently told the Bundestag that "wonder weapons" such as joint European bonds were not the solution. She also has publicly stated that adopting eurobonds would require changes to the German constitution and force existing EU treaties to be rewritten. The few remaining other euro zone countries with a triple A rating - Finland, Netherlands, Austria and Luxembourg - are also against eurobonds since they fear it would endanger their credit ratings.

Germany’s resistance to further bailouts also stems from the fact German unification showed just how incredibly expensive it can be to rehabilitate a poorer country. Since reunification in 1990, West Germans have funnelled 1.3 trillion euros to East Germany.

Unfortunately, the unintended consequences of Germany’s relentless push for austerity measures has been to weaken the standing of Europe’s traditional mainstream parties and undermine support for economic reforms. This in turn has led to the toppling of several governments and the rise of parties on the far and left of the political spectrums who are very critical of the EU’s policies, and in some cases even favour a withdrawal from the euro zone. The recent national elections in Greece and France, as well as the collapse of the government in the Netherlands, are only the most recent examples.

President Hollande’s Dilemma

Germany’s hard-line stance has placed the newly elected President Hollande of France in a particularly tough spot. Acutely aware of the resentment of many French citizens to the perceived dominance of Germany, he came to power pledging to take a tougher line. “She [Merkel] cannot be the sole decider of Europe’s fate based on German interests… We did not vote for there to be a president of the European Union named Ms. Merkel who decides on the fate of all others,” he recently said. He also needs to maintain a tough stance against Germany in order to do well in legislative elections scheduled for June 10th and 17th. However, the best Hollande can hope from Merkel is symbolic measures such as an enhanced lending role for the European Investment Bank.

Risk To Germany From A Greek Collapse And Euro Zone Exit

Many German politicians have publicly argued that the EU is much more prepared to withstand a Greek default and euro zone exit than it was a year ago. They note that much of Greece’s debt has been transferred from the private to the public sector and that the size of the EU bailout fund had been bolstered. The German public also appears not to fear the consequences of a Greek exit. A recent poll showed that 60% of Germans want Greece to leave the euro zone.

However, we continue to believe that the markets are underestimating the geopolitical and economic risks of this scenario. One could argue that Europe is in a worse position today to withstand Greek collapse now than when Greece got its first bailout in May 2010. Indeed, since then, the economies and debt levels of Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Italy have all worsened and public support for bailouts and austerity measures has significantly fallen. While the exact consequences of a Greek collapse cannot be predicted, this outcome could include the following components:

1. Germany and other creditor countries would be forced to recapitalize the bailout fund. This is after having assured their citizens this scenario would never occur, thus provoking a political backlash.

2. In an effort to limit the contagion, a second bailout would be needed for Portugal and Ireland. The bailout fund and/or the ECB would also have to purchase significant amounts of Italian and Spanish bonds, as well as provide bank financing, in an effort to calm market fears. Italy and Spain are the world’s 11th and 14th largest economies in purchasing power parity terms, versus 41st place for Greece. Last February, the Institute of International Finance estimated that in the event of a Greek collapse, Italy and Spain would together need 350 billion euros to stem a contagion.

3. The demand for increased funds to calm the markets would coincide with surging public opposition to further financial assistance. Opposition to further bailouts would rise from over 60% to 80% in countries such as Germany and the Netherlands. After all the time and money spent in the futile effort to save Greece, there would be very little confidence that that EU would be successful in saving Portugal and other countries from the same fate.

It is perhaps this fear of the impact of a Greek default that led the German government to indicate that it could be willing to relax payment deadlines, and reduce interest payments if a pro-bailout government is elected in Greece on June 17th, which, according to recent polls, is looking more likely. This would mean yet another round of negotiations with Greece.

Unfortunately, the sorry sate of the Greek economy means that regardless of the outcome of the elections on June 17th, it will not be able to make its debt commitments. This leaves Germany with the eventual choice of either giving Greece a debt write-off within the euro zone or letting it default in a forced exit.

The German Government’s Growing Vulnerability

In addition to dealing with political risk in neighbouring countries, Chancellor Merkel must increasingly face political headwinds at home.

Since March 2011, Merkel’s party, the Christian Democrats, has suffered a string of losses in state elections. This includes the states of Baden-Württemberg (for first time in 58 years) and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (Ms. Merkel's home state). The most recent loss occurred on May 13th in North Rhine-Westphalia, the largest state in Germany, with a population of 18 million. A coalition of Social Democrats and the Greens got a majority of 50.4%. Support for the Social Democrats increased to 39% from 35% compared with last election held two years ago, while support for Ms. Merkel's Christian Democratic Union dropped to 26% from 35%, its worst showing ever in this state.

One of the main issues of the campaign was anger over the imposition of austerity measures. North Rhine-Westphalia has a public debt of 180 billion euros. This situation has forced citizens to endure significant budget cuts. Ironically, while Merkel’s strict austerity approach towards Greece and other countries has a public approval rating of over 60%, the election results show that Germans are much less enthusiastic about cuts when they are the ones who are on the receiving end. This is similar to what happened in the Netherlands. It was one of the fiercest proponents of imposing harsh austerity measures on Greece, but when it came to cutting its own spending, the government collapsed due to infighting.

Another sore point that this election has revealed is the growing resentment by citizens of North Rhine-Westphalia at having to continue to transfer funds to East Germany more than two decades after the fall of the Berlin wall. Many Germans feel that these funds should be redirected to their own communities. If West Germans are grumbling about the costs of aiding their Eastern counterparts, one can only imagine how little support there is to providing long-term aid to indebted European countries.

Merkel’s string of state election losses has means that she now needs the support of the Social Democratic party to get the EU fiscal austerity pact approved. This is because law affecting Germany’s constitution and sovereignty require a two-thirds majority in the Bundestag (upper house) and the Bundesrat (lower house). But it is important to note that the only real difference between the government and the Social Democratic party is that the latter wants to put in place more (largely symbolic) growth-boosting measures, such as increased funding by the European Investment Bank. Both parties agree on attaching strict conditions to the bailout fund.

Despite her string of state losses, Chancellor Merkel is still the country’s most popular politician. Her party, the Christian Democratic Union, polls six to eight points ahead of the Social Democrats in recent polls. Unlike in much of the rest of Europe, where many resent Ms. Merkel's hard-line stance on austerity, her toughness is widely supported by Germans.

Nonetheless, if the government is having such a tough time winning state elections when the Chancellor is relatively popular and the economy is doing reasonably well, one can only imagine how much more difficult it would be for Merkel to win further elections should the economy take a turn for the worse. Barring the collapse of the governing coalition, national elections are scheduled for September 2013.

Conclusion

To date Germany’s economy has remained relatively immune from the EU crisis. However, the lagging economic performance of Europe together with slower growth in China will increasingly weigh on its economic prospects. On the geopolitical front, meanwhile, the citizens of struggling countries are turning against both Germany and its austerity plan. This has led to growing pressure from many countries, including France and Italy, for Germany to scale down its support for austerity and focus more on measures that will stimulate growth.

The problem is that this viewpoint collides with German public opinion, which strongly opposes further debt write-offs, increased deficit spending and eurobonds. Germans are also becoming increasingly angry at the incessant calls by other European countries for more and more funding. A weakening German economy would further strengthen domestic public opinion against bailouts, because citizens would increasingly demand why Germany is assisting other countries when there are growing needs at home.

Finally, the growing risk of a Greek collapse and mounting economic problems in Spain, Portugal and elsewhere brings into sharp focus Germany’s predicament. Regardless of who wins the Greek election on June 17th, the debts of Greece and certain other indebted countries will need to be significantly written down. And given that Germany is by far the largest contributor to the European bailout fund and the ECB, it will, one way or another, be stuck with the largest part of the bill. The consequences of Germany taking losses on its debt guarantees would be a major political backlash that could, in the worst case scenario, lead to the collapse of the government and new elections. This in turn would leave both Germany and Europe leaderless at a crucial moment. German opposition to further bailouts would also surge to record levels.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Tension Mounts Between Germany And The Euro Zone

Published 06/01/2012, 08:47 AM

Updated 05/14/2017, 06:45 AM

Tension Mounts Between Germany And The Euro Zone

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.