The parade of Fed speakers this week affirmed key messages from the Fed meeting last week: uncertainty about the outlook, some pessimism about inflation and growth this year with risks skewed toward stagflation, and a willingness to wait for more information before adjusting policy. The ‘information’ this week, above all, the new 25% tariff on imported motor vehicles and parts, continues to build the case for the worse outcomes, and a Fed likely on pause for several months, if not this year.

A Whiff of Stagflation in the Baseline Forecasts

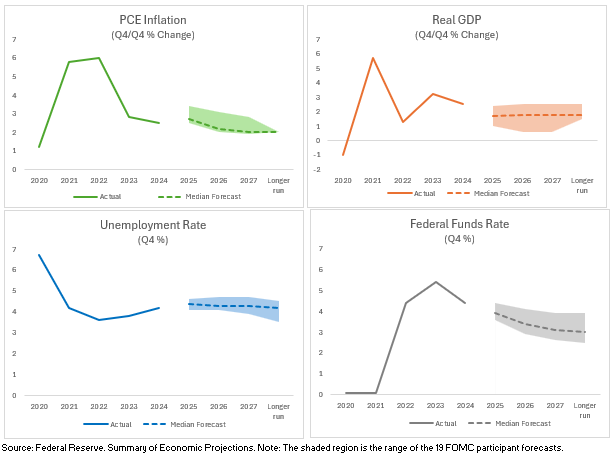

Last week’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) with forecasts from each of the 19 Fed officials, while not a consensus forecast, offers some clues on their current thinking. It shows a whiff of stagflation. The median forecast (the dashed lines in the chart below) showed PCE inflation as slightly higher this year than last, interrupting the downward trend since 2022. Meanwhile, growth is expected to slow to just below its longer-run trend after two years of strong growth, and the unemployment rate is expected to rise slightly. The full range of forecasts (the shaded areas) tells a similar story. My ‘whiff’ characterization reflects the relatively modest hit to growth and boost to inflation this year, as well as the quick, low-pain return to disinflation next year. These are not stagflation forecasts, but they are a shift.

In an interview this week, Atlanta Fed President Rafael Bostic was not enthusiastic about reviving the word “transitory,” which the Fed initially applied to the pandemic inflation and delayed rate hikes. “I’m not going to say that word,” he said. “Nope.” That said, even with higher inflation, he expects one cut to be appropriate this year.

There is some “pain” to the higher inflation in the form of fewer expected cuts from the Fed. The median forecast for the funds rate was a half percentage point lower in 2025 and 2026 than the current forecast. Even so, it is notable that even in the face of a new inflationary shock, Fed officials are unanimous that their next move is most likely to reduce the rate, and nearly all are comfortable cutting this year as inflation rises.

Low Confidence in the Outlook

Don’t get too attached to those fairly optimistic forecasts. The Fed isn’t.

Uncertainty is a key theme. The Fed mentioned it in the FOMC meeting statement, nearly all participants flagged their forecasts as more uncertain than usual, Chair Powell mentioned it repeatedly at the press conference, and it has been littered throughout Fedspeak since then.

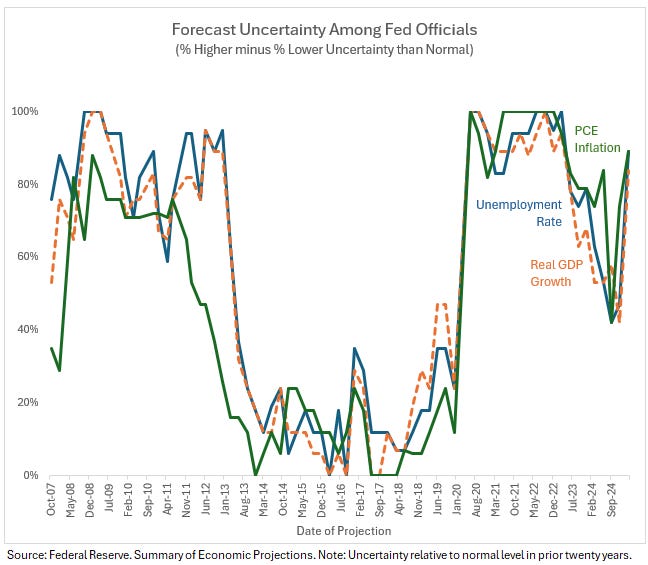

The Fed’s uncertainty index—the percentage of officials saying uncertainty around their forecast was higher minus the percentage saying it was lower than the normal level in the past twenty years—is elevated for growth, unemployment, and inflation (see chart below). Uncertainty jumped relative to before the election, which was in line with the surge in uncertainty about economic policy.

High uncertainty around a forecast generally signals a lack of confidence. With such high uncertainty, it should not be surprising that the Powell Fed has increasingly leaned on data rather than their forecasts in policymaking. Expect that orientation to continue. However, as Fed Governor Chris Waller argued recently, times of high uncertainty are not necessarily times of inaction. The Fed cut rates aggressively at the start of the pandemic—when uncertainty was so high that the Fed suspended the forecasts—and then raised them during the recovery as uncertainty persisted. Uncertainty does not stop action, but it typically raises the bar to act. Data are crucial to action. Waiting on sufficient data can slow things down.

Powell, in the press conference, reinforced the high degree of uncertainty:

I’m confident that we’re well-positioned in the sense that we’re well positioned to move in the direction we’ll need to move. I mean I, I don’t know anyone who has lot of confidence in their forecast. I mean the point is, we are -- we are at, you know, we’re at a place where we can cut, or we can hold, what is a clearly a restrictive stance, of policy. And that’s what I mean. I mean I think we’re -- that’s well-positioned. Forecasting right now, it’s you know, forecasting is always very, very hard, and in the current situation, I just think it’s uncertainty is remarkably high.

The Risks Are More Stagflationary

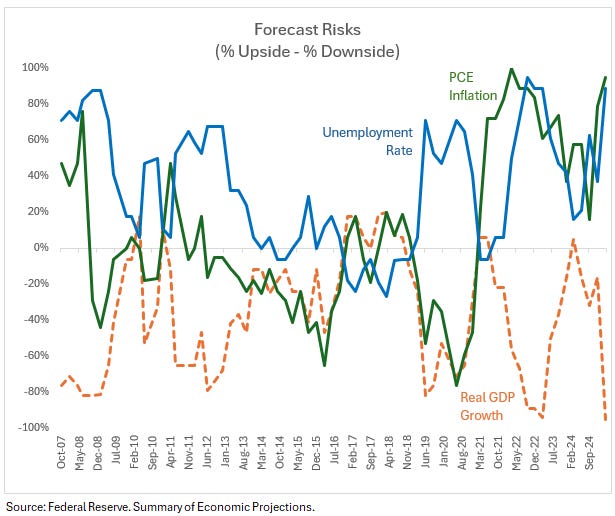

Fed officials see the chances of their forecast being wrong as higher than normal, but that’s just part of the story. They think they are likelier to be wrong in the direction of bad news: higher inflation, lower growth, and higher unemployment. The whiff of stagflation in the baseline is stronger in the risks they see as most likely.

It’s a good practice—though not always possible—to balance the risks around your forecasts. If all you can think of are reasons you could be wrong in one direction, then maybe that should be moving your baseline forecast in that direction.

In their latest projections, nearly all Fed officials see upside risks to inflation and unemployment and downside risks to growth (see chart). The risks are weighted toward stagflation. Balanced risks would be an index value of zero. Currently, the absolute average of the three indexes is 93%. The highest degree of unbalanced risks since the SEP began in 2007.

First, policy uncertainty, especially around tariffs, is high, and the Fed knows it will learn more about the administration’s plans soon. Presenting a gloomy outlook before the policies are even enacted could be seen as the Fed trying to play politics. It is not worth an attack on the Fed’s independence.

Second, a stagflationary outlook would be complicated for the Fed. The two sides of the dual mandate are in opposition, so the “appropriate” policy is debatable and nuanced. The SEP is not the place to have that debate, at least not yet. The risk assessments show that Fed officials are aware of stagflationary impulses. Internal debates about the reaction function are likely the better place to start.

The public remarks of Fed officials this week offer some color on the risks. President of the St. Louis Fed and voting member Alberto Musalem, laid out the risks:

I would be wary of assuming that the impact of tariff increases on inflation will be entirely temporary, or that a full “look-through” strategy will necessarily be appropriate. I would be especially vigilant about indirect, second-round effects on inflation. I would also be uncomfortable if medium- to longer-term inflation expectations begin to rise. With inflation already above 2% in a full-employment economy, the stakes are potentially higher than they would be if inflation were at or below target, and if consumers and businesses had not recently experienced high inflation, raising their sensitivity to it.

There’s good reason to be vigilant about indirect, second-round tariff effects. The cost shocks due to the pandemic created years-long ripples in the inflation data. The motor vehicle and related sector was a clear example. As I wrote last April, what started as sharp price increases in new vehicles due to shortages of semiconductors and supply chain disruptions led to bursts of inflation in used vehicles, repair services, and car insurance. The inflation in each sector was temporary, but the drawn-out adjustment process put upward pressure on overall inflation for multiple years.

It’s also a highly relevant example now. President Trump declared a 25% tariff on imported motor vehicles and parts this week. That will act like a cost shock on new vehicles and likely kick off a new set of ripples. Fed officials will require considerable time and data to determine whether the boost to inflation is temporary. A deterioration in the labor market could push them to move faster, but that’s no guarantee since inflation has been elevated for four years already.

In Closing

The smell of stagflation—higher inflation and lower growth—is noticeable in the Fed communications, especially when discussing the risks to the outlook. Even so, Chicago Fed President and voting FOMC member, Austan Goolsbee, was correct to set any stagflation concerns now in the proper context:

Tariffs, raise prices and reduce output. So that’s a stagflationary impulse, which is different from saying this is stagflation. The unemployment rate is barely 4% and inflation is in the 2s. So the hard data that we start from is not the stagflation of the 1970s. It’s just the ... the uncomfortable environment is when it’s moving directionally the wrong way.

The 1970s were a poor comparison to the pandemic inflation—above all, we did not need a recession to get pandemic inflation down. That same caution should be applied to tariff-induced inflation. Similarly, the pandemic won’t be the perfect guide either. Tariff-induced inflation has a better chance of being “transitory” since the demand destruction from lower real incomes should blunt some of the inflation. That’s little comfort. Stagflation, even if modest, would be costly.

High uncertainty, unbalanced risks, and stagflationary impulses are more than enough to keep the Fed on hold.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.