Investing.com’s stocks of the week

"There’s a healthy appetite for streams right now.” That’s according to Randy Smallwood, CEO of Silver Wheaton (NYSE:SLW), who stopped by our office last week during his cross-country meet-and-greet with investors.

Randy should know about the appetite for streams. His company had a phenomenal 2015—“the best year we ever had,” he says—highlighted by two successful stream acquisitions, strong production and fully-funded growth. Silver Wheaton stock is up more than 51 percent for the year. And the company just received the Viola R. MacMillan Award, presented by the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC), for “demonstrating leadership in management and financing for the exploration and development of mineral resources.”

We were one of Silver Wheaton’s seed investors in 2004. In the summer of that year, the company was spun off from Wheaton River, a producer that took its name from a stream in the Yukon where one of its mines, the Luismin property, produced silver. It was founded by Ian Telfer, chairman and CEO of Wheaton River, and the company’s then-chief financial officer, Peter Barnes, who later headed up Silver Wheaton management. My friend, the mining financier and philanthropist Frank Giustra, also had a hand in its conception.

As the only pure silver mining company, Silver Wheaton couldn’t have been founded during a more opportune time. The commodities boom was still young. I remember that when the idea for the company was shared with me, what I found most attractive was that it had virtually no competition. Franco-Nevada, (NYSE:FNV) which had been acquired by Newmont Mining (NYSE:NEM) in 2001, wouldn’t be spun off for three more years. It was a no-brainer to put capital in this new endeavor.

Wheaton River was eventually bought by Goldcorp (NYSE:GG), and today, Silver Wheaton is the world’s largest precious metals streaming company, with a market cap of over $9 billion.

But Wait, What’s a “Stream”?

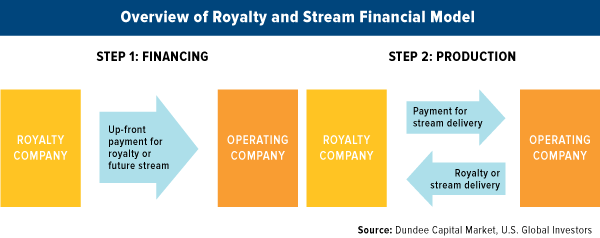

A “stream,” in case you were wondering, is an agreed-upon amount of gold, silver or other precious metal that a mining company is contractually obligated to deliver to Silver Wheaton in exchange for upfront cash. (The company’s preferred metal is silver because, as Randy puts it, it’s a smaller market and has a higher beta than gold.) The payment generally comes with less onerous terms than traditional financing, which is why miners favor working with Silver Wheaton (or one of the other royalty companies such as Franco-Nevada, Royal Gold (NASDAQ:RGLD) and Sandstorm Gold Ltd N (NYSE:SAND)).

Streaming allows producers to “take the value of a non-core asset and crystallize that into capital they can invest into their core franchise,” Randy explains in a video prepared for the PDAC awards.

With operating costs mounting and metals still at relatively low—albeit rising—prices, royalty and streaming companies have become an essential source of financing for junior and undercapitalized miners. Between 2009 and 2014, operating and capital costs per ounce of gold rose 50 percent, from $606 to $915 per ounce, according to Dundee Capital.

Gold and Silver at 15-Month Highs

Paradigm Capital estimates that between 80 and 90 percent of global miners’ operating costs are covered when gold reaches $1,250 an ounce. The metal is now at this level—it’s currently at $1,298, up 22 percent so far this year—but as recently as December, prices were floundering at $1,050, which cut deeply into producers’ margins.

Royalty and streaming companies, on the other hand, get by with a materially lower cost of $440 an ounce.

From only 11 stream sales in 2015, miners collectively raised $4.2 billion, which is double the amount they raised in 2013.

These partnerships are a win-win. The miner gets reliable, hassle-free funding to cover part of its exploration and production costs, and the streaming company gets all or part of the output at a fixed, lower-than-market price. A 2004 streaming arrangement made with Primero (NYSE:PPP) on the San Dimas mine in Mexico entitles Silver Wheaton to buy all of its silver for an average price of $4.35 an ounce. With spot prices now at more than $17.89 an ounce, up 29 percent year-to-date, the San Dimas property is one of Silver Wheaton’s more lucrative assets. (The mine represents an estimated 15 percent of Silver Wheaton’s entire operating value, according to RBC Capital Markets.)

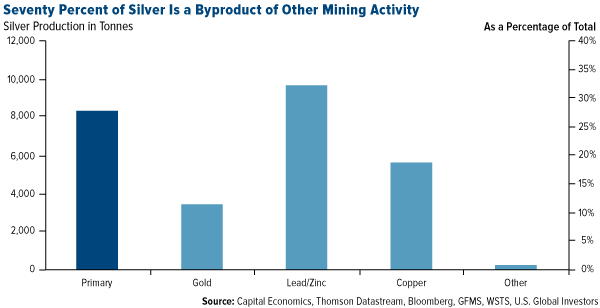

As part of its contracts, Silver Wheaton gets the added value of optionality on any future discoveries. This is important, since an estimated 70 percent of all silver comes as a byproduct of other mining activity, including gold, zinc, lead and copper. According to Randy, all of Silver Wheaton’s silver is byproduct.

Huge Rewards, Minimal Risk

Investors find royalty companies such as Silver Wheaton attractive for a number of reasons, not least of which is that they have exposure to commodity prices but face few of the risks associated with operating a mine.

They have minimal overhead and carry little to no debt. Franco-Nevada, in fact, added debt for the first time ever last year to buy a stream from Glencore (OTC:GLNCY). By year-end, the company had already paid down half this debt, and it plans to tackle the rest this quarter.

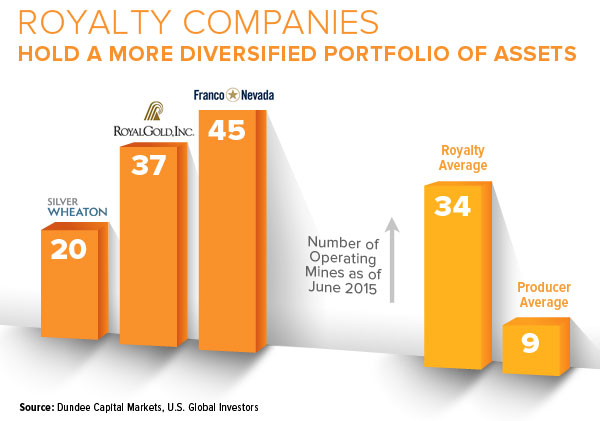

Royalty companies also hold a more diversified portfolio of mines and other assets than producers, since acquiring new streams doesn’t require any additional overhead. This helps mitigate concentration risk in the event that one of the properties stops producing for one reason or another.

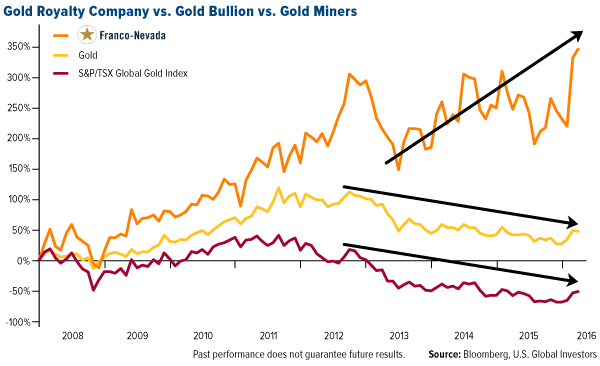

Consequently, margins have historically been huge. Even when the price of gold and gold mining stocks declined in the years following 2011, Franco-Nevada continued to rise because it had the ability to raise capital at a much lower cost than miners. And with precious metals now surging, royalty companies are highly favored, with Paradigm Capital recommending Franco-Nevada, which has “exercised the most buying discipline among the royalty companies,” and the small-cap, highly diversified Sandstorm.

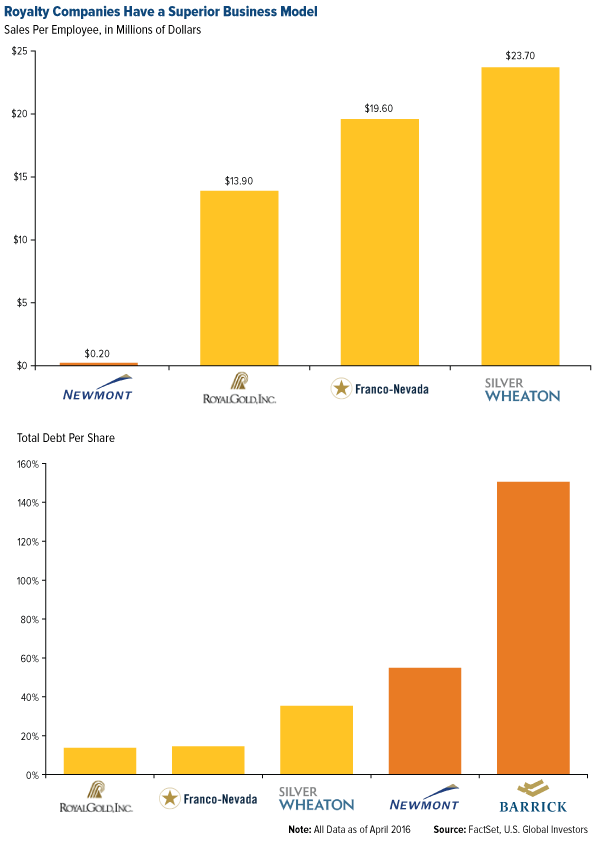

With only around 30 employees, Silver Wheaton has one of the highest sales-per-employee rates in the world. According to FactSet data, the company generates over $23 million per employee per year. Compare that to a large senior producer like Newmont, which generates “only” $200,000 per employee.

Royalty companies can often minimize political risk because they don’t normally deal directly with the governments of countries their partners are operating in. This is especially valuable when working with miners that operate in restrictive tax jurisdictions and under governments with high levels of corruption. Silver Wheaton’s contract with Brazilian miner Vale (NYSE:VALE), for instance, stipulates that Vale is solely responsible for paying taxes in Brazil, which are among the highest in Latin America.

Vancouver-based Silver Wheaton pays only Canadian taxes.

Political risk is still a thorny issue, however. When government corruption is too pervasive, or the red tape too tortuous, the miner’s corporate guarantee is obviously threatened. In cases such as this, Silver Wheaton can simply elect not to work with the producer, as it had to do recently with an African producer.

A key risk right now is Silver Wheaton’s ongoing legal feud with the Canadian Revenue Agency (CRA), regarding international transactions between 2005 and 2010. Randy says the company might finally be nearing a resolution to the dispute.

“We do have resource risk. We do have mining production risk,” he says. “But with that risk comes rewards, and I think if we’re selective in terms of our investments, the rewards far outweigh the risks. I think we’ve been really successful making sure we invest in good quality, high-margin mines. We really put a strong focus on mines that are very profitable.”

Disclosure: This commentary should not be considered a solicitation or offering of any investment product. Certain materials in this commentary may contain dated information. The information provided was current at the time of publication. All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor.