It’s not an unreasonable question. Certainly in Europe, few if any steelmakers are making any money.

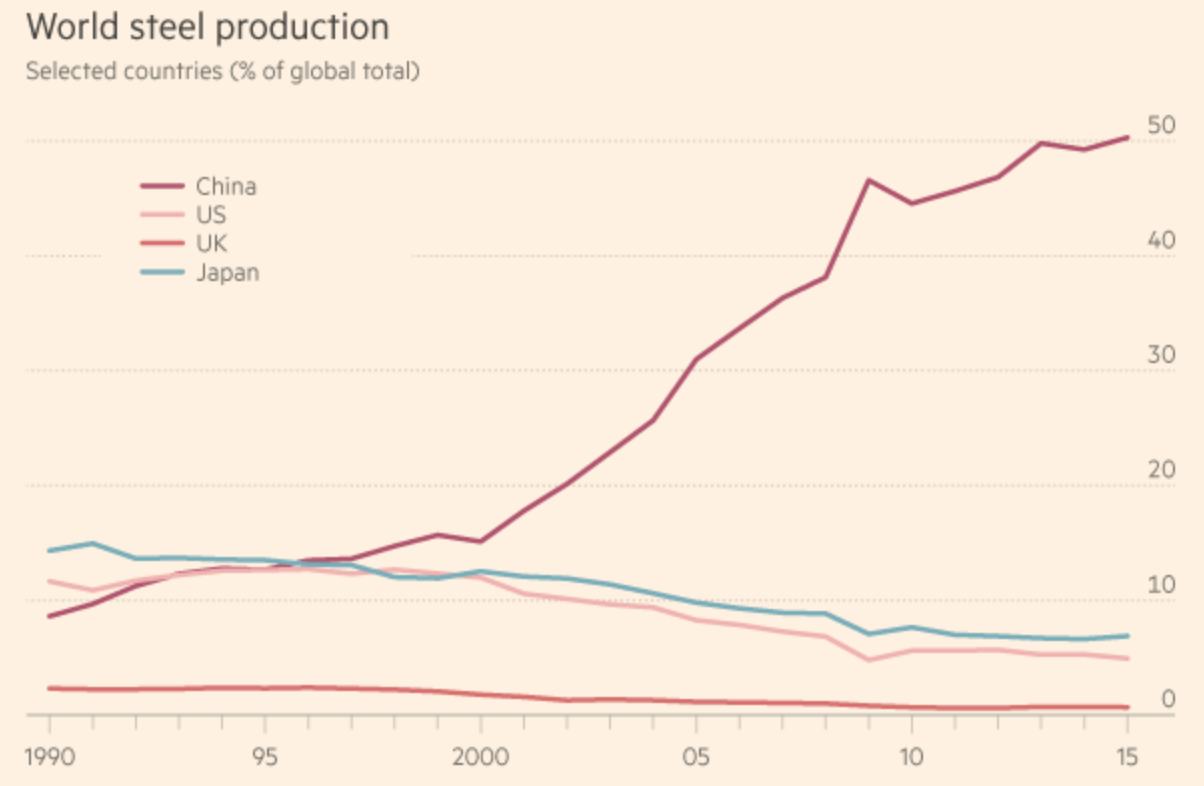

Capacity utilization is woefully low forcing steelmakers to fight for sales and depriving them of any price-setting opportunities. Steelmakers and much of the media lay the blame on China’s doorstep. Although over half of China’s major producers made losses in 2015, exports soared by 20% to 112 million metric tons last year, more than the total output of the world’s second-largest producer, Japan.

Source: Financial Times

Meanwhile, Europe’s steel demand is 25% lower than before the 2008 financial crisis according to the Financial Times and, although there has been some rationalization, it has been limited.

The Future of European Steel

Alessandro Abate, an analyst at Berenberg, is quoted by the FT with a hard hitting but no doubt accurate comment: “The future of [European] steel lies in consolidation. If they don’t do it now they should stop complaining about Chinese overcapacity. They need to lower costs and distribute the workload across the most efficient assets.”

While there is much truth in this, the issue is probably more profound than just consolidation. Wolfgang Eder, chief executive of Voestalpine AG (LON:0MKX), an Austria-based producer had this to say about it.

“The European cost structure does not allow you to produce steel commodities in a competitive way. When you look at the world, 80% at least of the total steel production is commodities,” meaning if steelmakers in developed markets continue to take on China’s subsidized steelmakers in the commodity end of the market, they will continue to lose money.

In Eder’s opinion, steelmakers need to develop flexibility — since it is a highly cyclical business — and focus on high-quality, high-technology steel products. Not surprisingly, he is pointing to his own firm as an example. To be fair he has a point. When British Steel and Hoogovens consolidated in the late 1990’s and Arcelor (NYSE:MT) and Mittal Steel merged in the following decade it was all about size and economies of scale to pump out commodity steel products.

A Changing Industry

Meanwhile Voestalpine concentrated on downstream investment in processing and value add engineering capabilities. Today about two thirds of the group’s €11bn revenue come from sales of engineered components, complete structures and high-tech parts, such as for automobiles and aircraft. This has helped shielded Voestalpine from some of the downward pressure on prices from cheaper products from emerging market competitors.

Rivals see the logic, ArcelorMittal announced this week the introduction of their new automotive steel Usibor 2000 said to be one-third stronger than those currently available for automaking and allowing car companies to reduce weight without making the switch to more costly aluminum.

Yet, such opportunities are limited. Niche areas by definition are, well, niche, so volumes are lower. When demand fluctuates running expensive blast furnaces can be a drain, they can’t be turned on and off quickly yet require massive investment to build and represent a huge capital cost.

Historically, ArcelorMittal’s approach of rolling such automotive sheet from blast furnace cast slab has been the accepted practice but in the U.S. Nucor (NYSE:NUE) has become the largest U.S. steelmaker in part because of the greater flexibility the electric arc furnace production route allows them and, in part, through innovation.

EAF plants usually produce long products but Nucor rolls sheet used in demanding applications such as automotive steel from its EAF furnaces. Interestingly, one of the “solutions” proposed for saving TATA STEEL (NS:TISC) U.K.’s Port Talbot steel mill is the replacement of the plant’s blast furnaces with EAF technology. Such innovation may come too late for Port Talbot, but investment in downstream value-add steelmaking technologies and processes remains the best long-term solution for Europe’s steelmakers.

by Stuart Burns