After seven years, the Federal Reserve finally did the unthinkable by raising the Fed Funds rate by 25 basis points. For years I’ve heard many investors and professionals talk about moving money into short-term bonds because of the risk of rising rates and the eventual end of the great bond bull market.

While I generally agree with the overall sentiment here, it’s a given that interest rate sensitivity is greater as the duration gets longer. The problem is that each end of the yield curve doesn’t always move in unison. So by over-allocating to the short end of the curve, investors may very well be piling into the same end of the curve that might be most effected by a gradually rising Fed Funds rate.

In fact, if you tell me that we are going to continue to see sluggish economic growth in the 2% range while the Fed Funds rate gets raised, I’d say there is a good chance the long end of the yield curve won’t move nearly as much as the short end, effectively flattening the curve.

If you tell me economic growth is going to pick up above 3% for the foreseeable future, then I’d be more inclined to be cautious on the long end as well. However, economists and Fed forecasts have been predicting a stronger pickup in real GDP growth since 2012, and so far it’s been spotty at best.

So what I’m saying is that I don’t feel investors are getting compensated enough for the risks they take in short-term bonds and short-term bond funds. I’m sure this is a contrarian opinion.

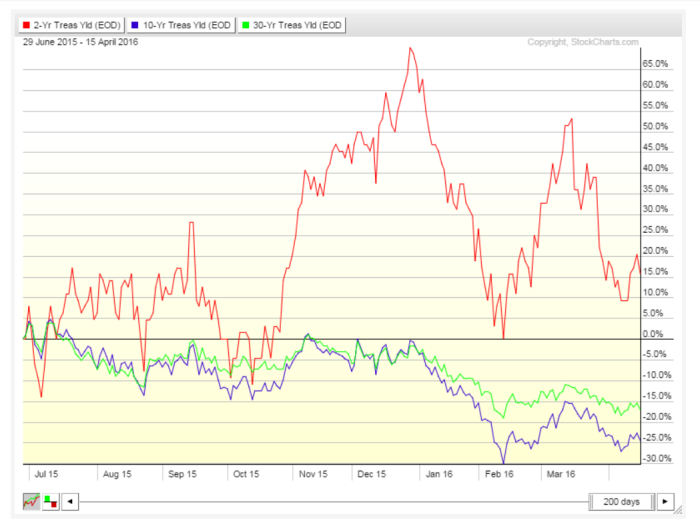

Let’s take a look at the last 16 months as an example. I understand that it’s a very small sample size, but it helps illustrate the overall thesis.

The above chart is the yield on 2-Year Treasury bonds. From October 2015 into the end of the year, in anticipation of the first Fed Funds rate hike, the yield went from 0.57% to 1.09%, for an overall increase of 91%. During the rally in equities off the February 2016 lows, the 2 year Treasury yield went from 0.64% to 0.98%, for an overall increase of 46%.

Now let’s look a little deeper out on the yield curve and observe the 10-Year Treasury yield during this same time frame. The October rally in yields took the 10-year from 1.99% to as high as 2.36%, for an overall gain of 18.59%. The February rally took the yield from 1.63% to 1.98%, for an overall gain of 21.47%. And the 10-year yield is actually lower now than it was 16 months ago, whereas the yield on the 2-year Treasury is almost double what it was 16 months ago.

Last, we’ll look at the far end of the yield curve. Observe the price action in 30-Year Treasury bond yields. During the October 2015 rally in yields, the 30-year went from 2.82% to 3.12%, for an overall increase of 10.64%. And during the February 2016 rally, the yield went from 2.50% to 2.75%, for an overall increase of 10%. And like the 10-year, the 30-year is also lower than where it was 16 months ago.

So it’s ironic that after hearing so much about how rising rates would crush longer duration bonds, it’s actually the short-term yields that have performed the best so far. Now I understand the reasons for this (negative yields, slow economic growth and low inflation expectations) but what I’m saying is that rather than investors overreacting to these predictions, it’s better for them to have an understanding of just what purpose bonds hold in their portfolios.

If your purpose for bonds is to hedge against a bear market, then there is no reason to abandon long- and intermediate-term Treasury bonds. They’ve historically done a good job when investors need them most. And if you hold a long-term Treasury bond index fund, the rising rates will be somewhat offset by the higher future yield as the fund is able to acquire new bonds that pay higher rates of interest.

If your purpose for bonds is performance, then you could be disappointed going forward. It’s going to be tough to generate the same type of returns investors have gotten used to over the last 30 years. Not that it wouldn’t be possible, just unlikely. Historically, intermediate-term bonds have done a pretty good job of providing the best risk adjusted returns.

Many investors have flocked to high yield and investment grade corporate bonds and even emerging market bonds to pick up that extra yield. While I believe anything in moderation is fine, I personally like to take my risks with stocks and leave the bond portion of portfolios to high quality Treasury bonds of different durations.

The other equally important aspect is cash flow needs. Like stocks, longer duration bonds shouldn’t be invested in with money that may be needed in the near future. For shorter term cash needs, there is a natural gravitation to these short-term bond funds. However I question the relative risk-to-reward of these funds as opposed to a short-term CD or even a money market fund.

The thesis here is not to persuade investors to make tactical changes to their portfolios, but rather to challenge the perception of investor belief that they can perfectly time, and thus avoid, loss from these macro interest rates moves. Good luck with that!