Contrary to so many other elements of the trade relationship between China and the rest of the world, supply chain experts had come to expect a relatively benign relationship between the yuan renminbi and the US dollar. Over the past decade, China’s central bank has either permitted the renminbi to creep slowly upward against the US dollar—at a pace considered glacial by the standards of foreign exchange markets, the FT reports in a recent article—or held it steady in times of stress, such as the global financial crisis of 2008-09.

But this week’s flash devaluation, by as much in one week as the currencies have moved in the last year, has sent shock waves through the markets and upset the long-held and, in hindsight, somewhat complacent view that, at least in terms of that currency pairing, the renminbi was destined to rise with the dollar.

Economic Aftershocks

In many ways, the shock is greatest for China’s Asian competitors who had planned on a continued appreciation and are now faced with the possibility of a more competitive China on their doorstep.

You would expect China’s exporters to be delighted with the move, but a combination of gradually appreciating currency since the dollar peg was removed in 2005 and rising inflation—particularly wage inflation—has resulted in many Chinese manufacturers finding themselves at a considerable disadvantage to competitors in Bangladesh, Vietnam and other low-wage countries even after this modest devaluation.

Such manufacturers of low-value products, such as textiles, were looking for a renminbi devaluation in excess of 10% against the US dollar, and who is to say that that may not come about? Beijing is clearly rattled by the slide in the economy’s GDP, by some measures the real growth rate is well below the headline 7% and still falling so we should not rule out the possibility of further falls in the exchange rate.

Borrowing Boondoggle

However, Beijing will also have one eye on debt financing. To the extent that exports may be boosted by a lower exchange rate, debt financing costs are increased. Not just China, but many developing countries that have borrowed heavily on the external finance markets have been fearing the impending rise in the Federal Reserve prime rate and the accompanying rise in the US dollar that will—it is widely expected—accompany the Fed’s move.

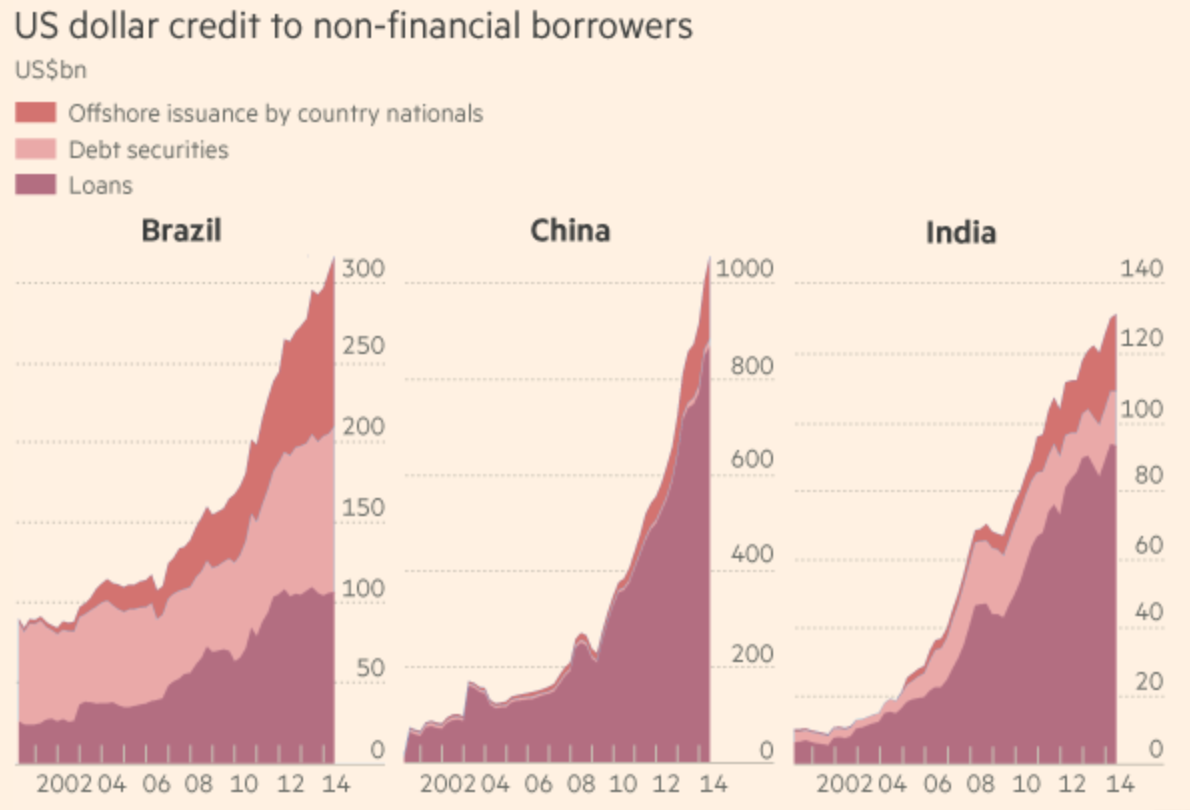

As the US dollar has risen this year against global currencies, companies and states have found their external finance costs increase. China is far from alone in this respect and is much better prepared with huge US dollar foreign reserves to weather such a rise, but other developing market economies are not so fortunate as this graph from the Financial Times based in BIS data illustrates the extraordinary rise in debt levels

Source: Financial Times

The FT uses a couple of examples to illustrate the problem at company level.

Debt in Dollars, Income in Yuan

China Southern Airlines (NYSE:ZNH), Asia’s largest carrier apparently, had more than $16.5 billion in dollar-denominated debt at the end of 2014. According to the FT, every 1% fall in the value of the renminbi costs it almost RMB 770 million ($120 million) in additional debt servicing costs. Chinese property companies, who were in trouble before this week’s fall in their share price, are in a similar bind, the paper says. Property companies have issued large amounts of high-yield US dollar bonds offshore to finance land purchases in China. They are now caught in a pincer with their income mostly in renminbi but debts in dollars, the depreciation will add further pressure on their balance sheets.

Zhou Hao, an economist with Commerzbank (XETRA:CBKG) is quoted as predicting that Chinese oil companies and commodity traders would also be badly hit by a weaker renminbi. Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) appears to agree, saying this week in Reuters that China’s devaluation signals that global economic conditions have taken a turn for the worse, creating more downward pressure on commodity prices.

In a separate article, we will be exploring the situation for steel and aluminum where anti-dumping concerns were already on the rise following a flood of steel and aluminum exports from China into western markets.

For now, we have to wait and see. Foreign buyers may see this as an opportunity to reduce dollar purchase costs from Chinese suppliers but this could be the first of several currency devaluations and buyers may be better advised to establish the principal of a dollar cost reduction now and await developments over the coming days and weeks rather than rush to negotiate a reduction on the back of this change only to find they are back at the negotiating table in a few weeks time.