SEK: small but business cycle-dependent impact on inflation

Inflation dynamics - what are the risks?

Riksbank expectations have been scaled back too much and upward pressure on 3M (NYSE:MMM) STIBOR: pay the 1Y SEK swap

KIX forecast scrutinised

SEK: small but business cycle-dependent impact on inflation

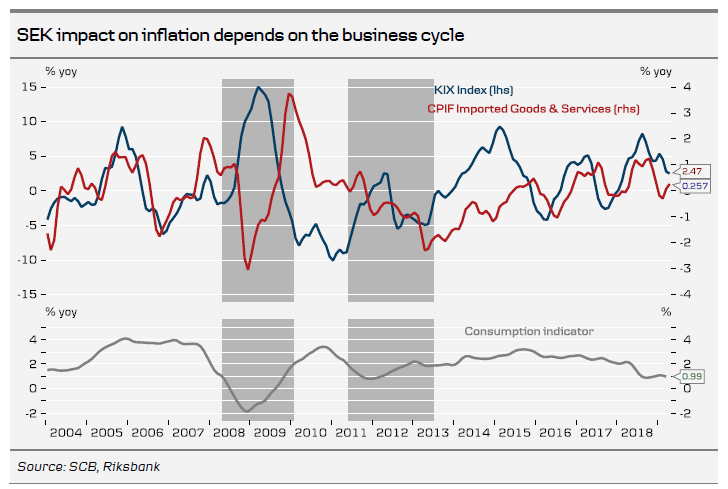

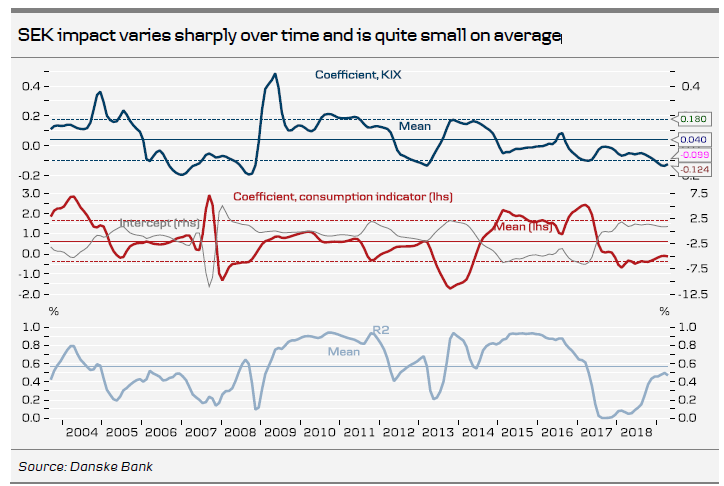

It is very hard to determine the impact from the SEK on consumer import prices (= 30% of CPIF). We can see that import price inflation (with a lag) occasionally co-varies nicely with the 12-month change in the KIX index. However, that relationship breaks down from time to time, for instance in connection with the financial crisis in 2008-2009 and the Euro crisis in 2011-2012. In the chart below it is obvious that FX movements become secondary and it is the state of the business cycle that is the prime determinant (here in the form of consumer spending growth) of import price developments.

We have estimated a simple regression model of CPIF import prices on 12-month change in KIX (lagged 9 months) and the 12-month change in the consumption indicator (lagged 1 month). The result is not very impressive, R2 = 0.13, i.e. it is not even possible to talk about our variables as explaining movements in import prices. The impact from the SEK is 0.06 (beta coefficient) in line with what we estimated before: a 10% weakening lifts import inflation by a mere 0.6pp, which is 30% of CPIF and hence the final impact is only 0.2pp higher CPIF inflation. Hardly an efficient transmission mechanism.

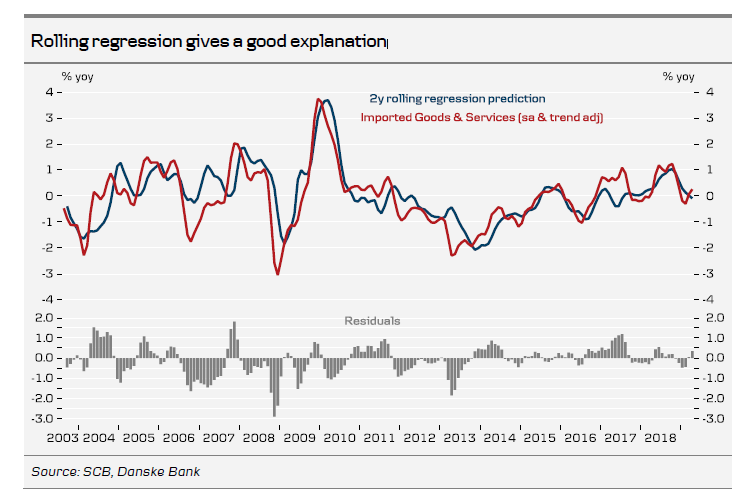

The regression shows that R2 on average is a moderate 60%, but under stable business cycle conditions it rises to 80-90%, which is more than OK. However, it is also clear that the impact varies sharply and is even negative during a large part of the time! This may appear unreasonable, but is it really? Before moving on to that we can just conclude that the coefficients for consumption growth co-vary negatively with the intercept, suggesting they should perhaps be seen as one factor altogether.

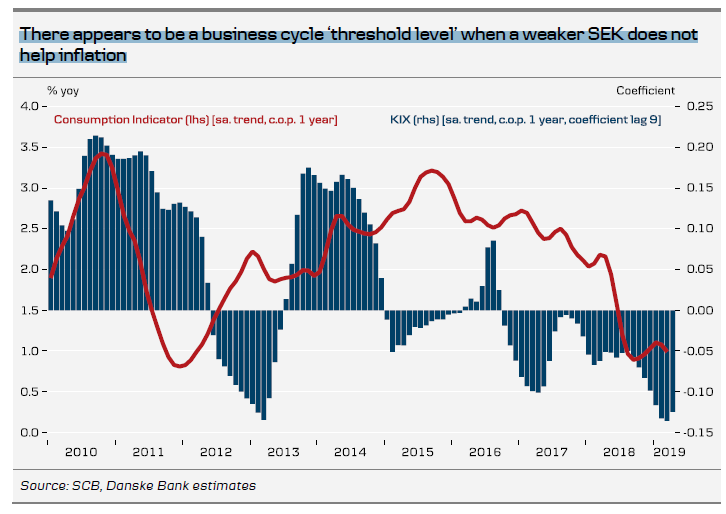

A simpler way to show this is in the chart below where we look at developments from 2010 and onwards. There appears to be a tendency that as long as consumption growth outpaces a certain ‘threshold level’, say 1.5% y/y, the SEK has a positive and rising impact (say, maximum 0.2 and on average perhaps half of that) on import inflation. However, as consumption growth drops below this level, the impact becomes negative instead. It is not entirely unreasonable when you think about it. It may be that retailers have bigger problems to handle when the business cycle and consumption growth slow than to compensate for a weaker SEK. In our estimate this turns up as a negative coefficient value during these periods.

Summing up, our study led to the following conclusions (should not be over interpreted). (1) The impact from the SEK on import prices depends on the state of the business cycle. (2) In good times when consumption grows more than say 1.5% y/y, the impact from a weaker SEK is positive and in the 0.05-0.2 range.

(3) When the business cycle deteriorates and consumption growth falls below 1.5%, a weaker SEK does not raise import inflation.

It means that the maximum impact from the SEK in good times can be 10 % weaker * 0.2 * 30% weight = 0.6 percentage points on CPIF but only temporary. On average (in good times) the impact is half of that. Currently, with consumption growth below the threshold at 1% y/y, we do not expect the weaker SEK to show up in inflation.

Inflation dynamics - what are the risks?

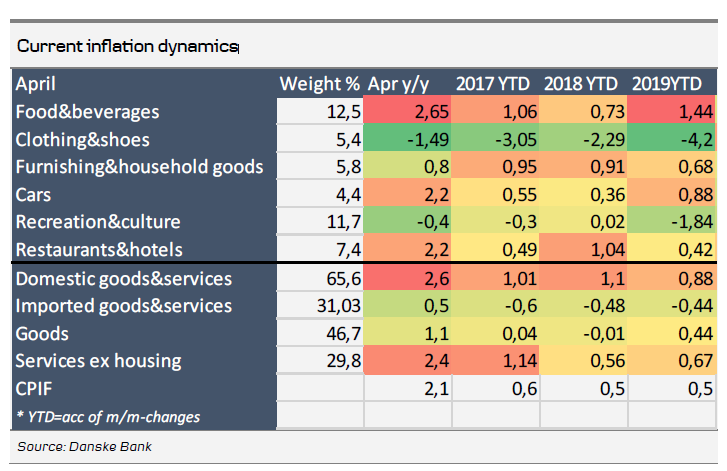

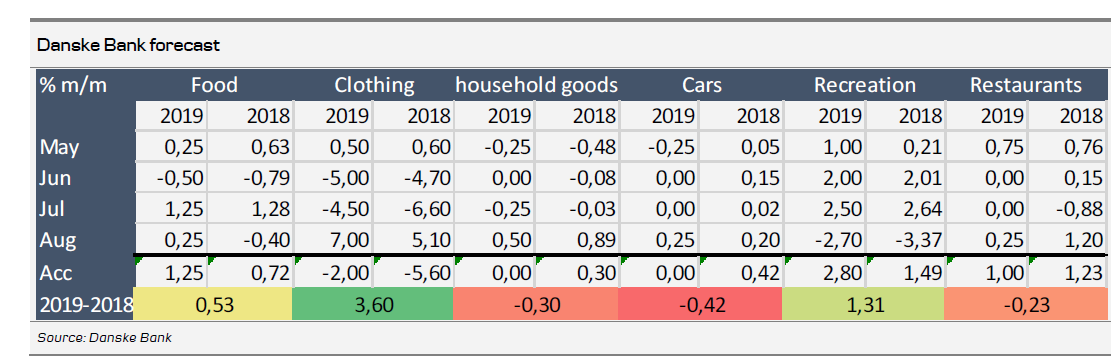

As mentioned above, the consumption indicator is currently running below the threshold level (1.5%) under which consumer prices typically do not respond to a weaker SEK. Nevertheless, considering that the SEK has weakened during quite a long period, there may be reasons to identify risks in our forecasts over the next few months. We do that by looking at current inflation dynamics for six important categories in the CPI basket.

The table above shows the latest y/y rates (April) and accumulated m/m changes January- April (YTD) for the last three years, the latter to give a view over the latest inflation dynamics.

It can be observed that import price inflation, the weak SEK notwithstanding, runs considerably lower than domestic price inflation (in a sense a positive thing from a Riksbank perspective). Regarding import price inflation, it is worth noting that inflation dynamics do not really suggest that it is starting to build up. YTD price changes this year (-0.44%) do not deviate in any meaningful way with YTD-2018 (-0.48%). This seems to be in line with the econometric results discussed earlier.

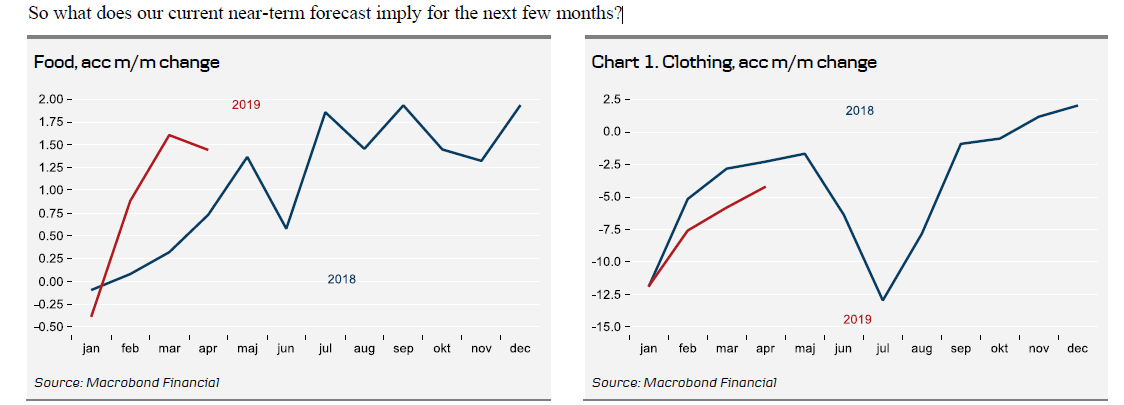

Turning to the six individual categories we start with two items that both are (to a varying degree) exposed to imports – food and clothing.

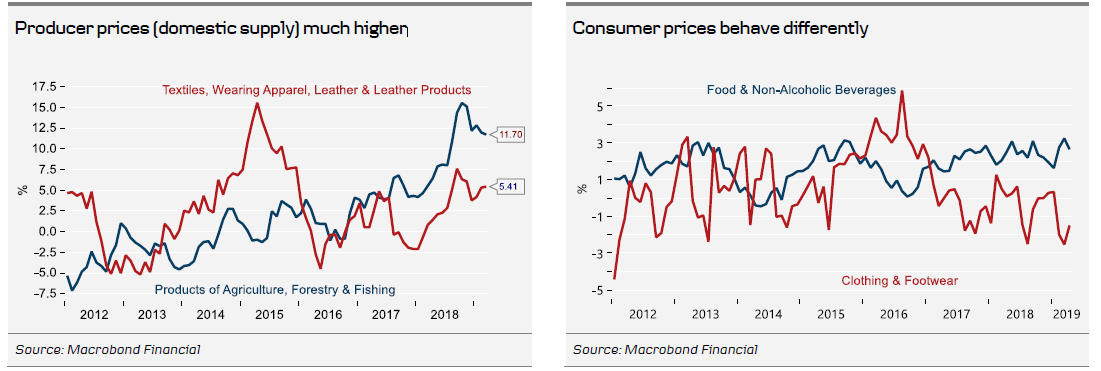

The left hand chart shows domestic supply prices - a combination of imported and domestically produced goods - for food and clothing. Both have risen considerably reflecting a weaker SEK. Food products have risen substantially more though, and we suspect this is due to lagging effects from last year’s drought. At the CPI-level though, the curves behave differently. Higher producer prices have been passed on to consumers as far as food is concerned but not clothing. Also observe that when producer prices for clothing surged in 2015 this was passed on to the consumer eventually. In line with what we discussed above, it might be that consumer spending was much stronger in 2015-2016.

One could argue that we have seen most of the effects on food prices from last year’s drought by now. Also we now approach the season when a larger proportion of food supply is produced domestically (fruit and vegetables), i.e. less of an impact from the SEK. Still, we have assumed that total price increases through August will exceed last year’s numbers by half a percentage point, bringing food price inflation to around 3% (close to the peak earlier this year). We see that as a reasonable ‘safety margin’.

Judging by our econometric study, retailers in clothing will have a hard time raising prices. Nevertheless we have assumed some ‘catch-up’ in the months ahead. Note that we are now approaching a season when clothing prices due to sales are going down. Last year prices were reduced by in total 5.6% in May-August. This time around we look for smaller discounts of 2%, pushing up the y/y rate from -1.5% to 2.1% by the end of the period. So it is in our view not in food or clothing (or recreation) where we primarily see risk of upside surprises in our forecast. Instead, it might be that our forecast is somewhat too modest for household goods, cars and restaurants, maybe primarily the first two since restaurants are only indirectly affected by the exchange rate (via food prices). Then again, food, clothing and recreation represent a larger share of the CPIF than the other three, so net-net it appears that our forecast includes sufficient safety margins for additional SEK effects, had it not been for one thing, which we have not mentioned so far – gasoline prices.

We typically make an active forecast for the current month, for succeeding months we only include a seasonal pattern but no trend. Undoubtedly, the combined effect of higher oil prices and higher USD/SEK has pushed Swedish gasoline prices to an all-time-high and admittedly we do not see a strong reason to expect an imminent turnaround. So, it might very well be that we will have to hike our projection for gasoline in coming months.

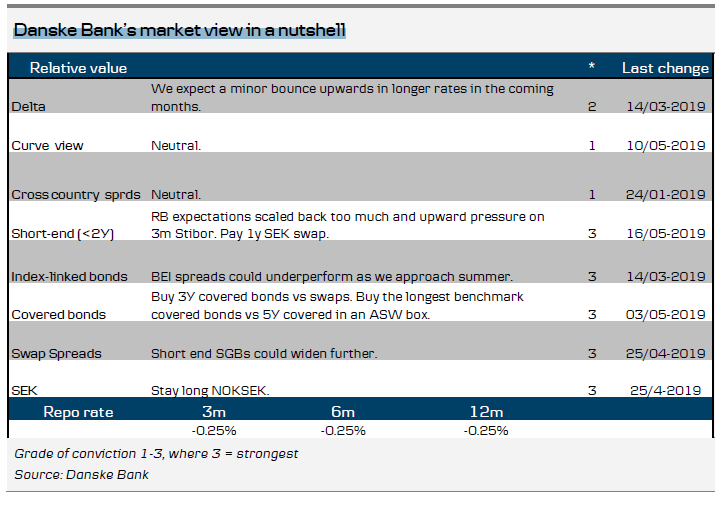

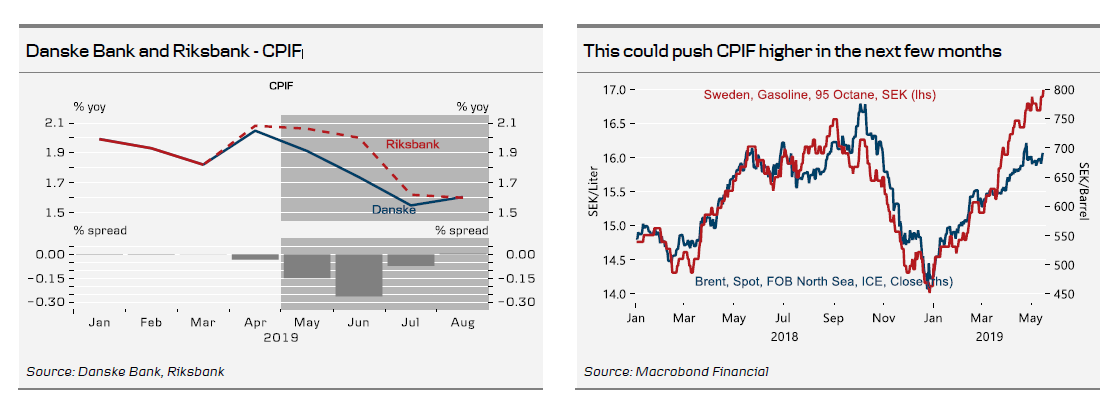

The Riksbank, taken by surprise by low inflation (and soft messages from ECB et al), lowered the near-term inflation forecast and pushed the next rate hike further out at the April meeting. In the coming period up to August we think the risks are more balanced and possibly slightly skewed to the upside depending on oil/gasoline prices. Put differently, the case is less compelling for another downward revision of inflation and the repo rate path at the next policy meeting in July.

In the meantime, market pricing has almost taken out another rate hike this year (only 2bp left in Riba). To go further down, effectively starting to price in cuts is not warranted, we think. Instead it might be time for a short-term correction. Also we are approaching a period where we expect to see some renewed upward pressure on STIBOR-fixing. That is why we are discussing paying a 1Y SEK swap below.

Having said that, this is not a trade to hold ‘for ever’. Later this year the story goes in reverse. The Riksbank’s inflation forecast from September assumes a big jump over just a few months, but we do not really see where it would come from. That is a story for later this year, however.

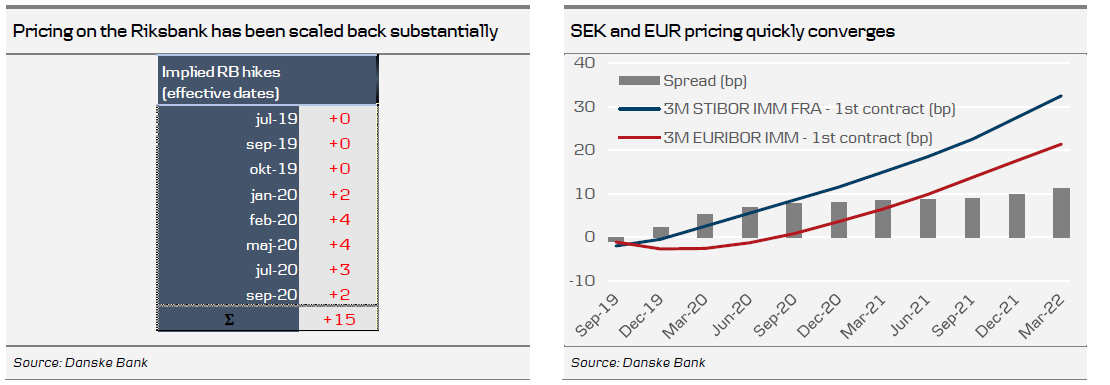

Riksbank expectations have been scaled back too much and upward pressure on 3M STIBOR: pay the 1Y SEK swap Since the April meeting, Riksbank expectations have been scaled back significantly.

Admittedly, the combination of postponed rate hikes and continued bond reinvestments was, to us at least, surprisingly dovish. However, the Riksbank minutes revealed that the board’s fundamental assessment of the Swedish economy and inflation outlook had not really changed that much. For instance, Governor Ingves states that ‘for 2020-2021, growth of just under 2% is expected, which is about the same assessment as in February. These are relatively healthy figures, especially bearing in mind the recent modest growth in the euro area’. The same old battle lines between board members are still in place, with Governor Ingves in our view still holding the swing vote.

We still believe that the most recent inflation forecast is challenging during the fall to say the least, as we have pointed out previously. On top of that, the Riksbank probably cannot afford a further weakening of the labour market. Ironically, the board member that highlighted that unemployment has stopped falling was arch-hawk Henry Ohlsson. He was, however, quick to dismiss it for various reasons (structural problems, job seekers supposedly having become pickier). Nevertheless, if unemployment starts grinding slightly higher, it may become increasingly hard for the Riksbank to ignore.

However, expectations of a move in late 2019 or early 2020 have been scaled back dramatically. Only around 2bp are priced for the whole of 2019. After that, Riksbank pricing converges relatively quickly with ECB pricing, as has been the case for quite some time. This can be seen in the chart below where we have taken each IMM contract for 3M STIBOR and 3M EURIBOR and subtracted the front contract. From this, we note that the SEK curve flattens out against the EUR curve from the Sep20 IMM contract and onwards.

Over time, the market has probably become more cynical about forecasted Riksbank hikes. However, with such a tilted market pricing, we think it would not take much for pricing to move. Even though we think our CPI forecast already takes into account the SEK depreciation, the pass through from the currency to inflation is a source of uncertainty. A global shift in risk sentiment would probably affect the Swedish short end as well.

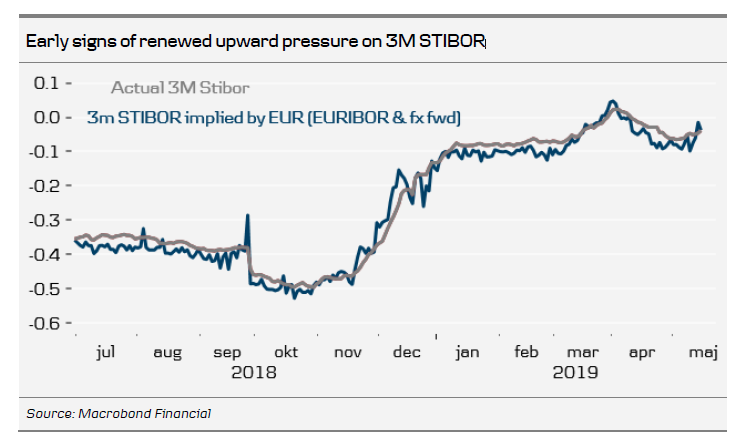

On top of that, we remain convinced that the 3M fixing is likely to move higher in the short term. We reason that the proposed LCR requirements in the SEK have likely already been implemented by Swedish banks (which would explain the increased volatility in 2019) and upcoming bond maturities in June 2019 (five bonds with an outstanding volume of SEK88bn as of end-April) will put pressure on LCR ratios in SEK. We expect that to play out either through more demand for HQLA in the form of Riksbank certificates (which would drain away excess liquidity) or through increased demand for SEK funding through the FX swap market. In practice, it may be difficult to separate the two channels. We note that the most recent auction for Riksbank certificates (on 14 May) was oversubscribed, leaving little excess liquidity in the system. If that continues, the 3M fixing should at least be able to surpass the levels we saw in March around the maturity of SGB1052 (0.023%).

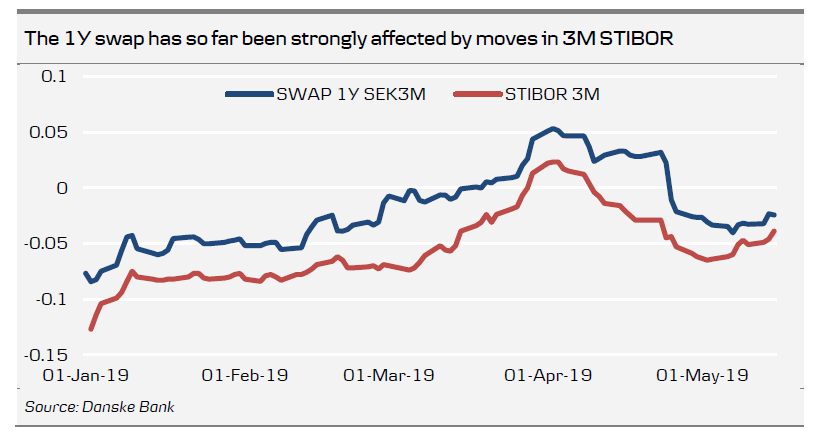

As can be seen in the chart below, the 1Y swap tends to track the 3M fixing, as the whole FRA-Riba strip tends to be affected by the spot fixing spread. In our view, the downside in the trade primarily relates to the fixing spread component of the swap. It would be quite odd to start pricing in rate cuts on a central bank still firmly set on hiking, unless there is a significant deterioration in the global growth outlook.

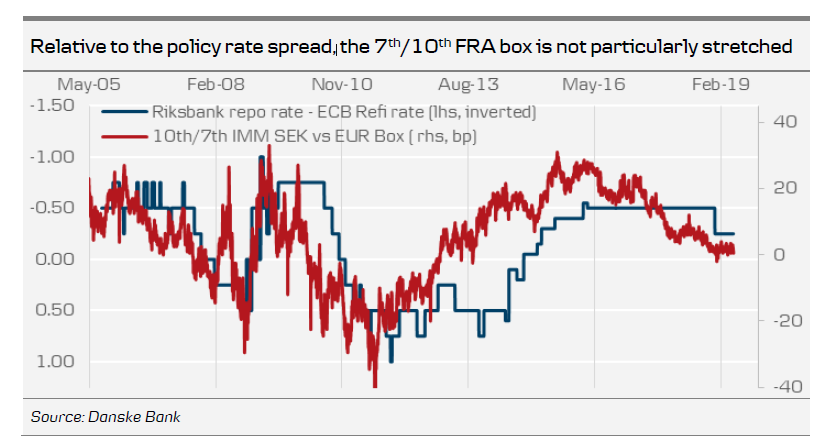

As an alternative to the 1Y swap, it might look compelling to steepen the SEK curve against EUR in a FRA box, as current pricing puts these slightly above zero. In the chart below we have used the 10th versus the 7th IMM contract, which is the flattest SEK FRA box versus 3M EURIBOR. Historically, however, this FRA box correlates well to the spread in policy rates and at times, even when the Riksbank repo rate was above the ECB refi rate, it has traded well into negative territory. So the current level just above zero is not really standing out in our view.

Thus, we find the risk/reward in paying the 1Y swap more attractive overall and recommend paying the swap outright. We set the P/L levels to +4.5/-7bp (start: -2.5bp).

KIX forecast scrutinized

In the latest Reading the Markets Sweden we highlighted a number of fundamental factors, which in our view have been a headwind for the SEK, not only the past few years but over a longer time period: the trade balance in goods has turned negative and the current account surplus is basically gone, productivity growth has deteriorated and terms of trade, at least during the first decade after the turn of the millennium, trended lower. Circumstances that in different ways suggest that Sweden has become less competitive as a nation, despite the substantial depreciation of the SEK.

One could turn it around and say that worsened competitiveness has in fact, beside monetary policy divergence, contributed to and justified at least part of the SEK weakness. Today we learnt that the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise (Svenskt Näringsliv) made a similar analysis in which it mentions loss of competitiveness. Of course, this is a way of positioning ahead of the wage negotiation round: the conclusion is that wage growth must be held back and wage dispersion increase. Hardly what the Riksbank needs to hear (it still has a too optimistic wage forecast, in our view). How to solve this conflict of goals? Continued SEK depreciation year after year?

We have for a long time argued that the pass through from the exchange rate to growth and inflation has weakened – that the currency weapon is more blunt than it used to be: net exports have not helped GDP growth, import price inflation hovers around zero and the second round effects onto consumers are muted due to globalisation, digitalisation, fierce price competition and global supply chains. Judging by recent comments from the Riksbank, it seems to have reached a similar conclusion.

Instead, it will be very interesting to see what the so called ‘rethink’ of the exchange rate analysis will bring (probably in an upcoming Monetary Policy Report). The reason why it sees a need to rethink is obviously related to the systematic forecast errors over the years (chart below). A not too bold a guess is that the analysis among other things will focus on the factors mentioned above. The outcome could be a flatter KIX path (less SEK appreciation). How it deals with this will be important for how it is received in the markets. On the one hand it could be interpreted as bearish for the SEK: ‘even the Riksbank has thrown in the towel when it comes to SEK appreciation’. On the other hand it could be SEK bullish: ‘a weaker SEK in the forecast mechanically a higher inflation path earlier rate hikes’ – not ruled out, though we would not bet on it.

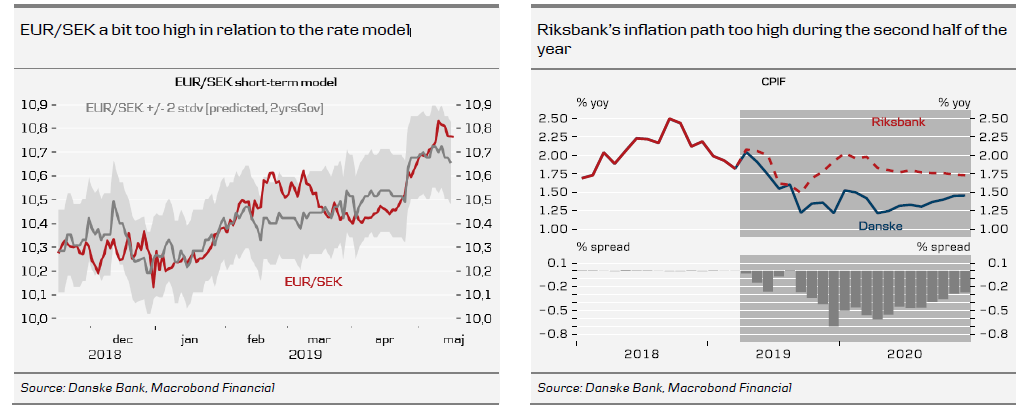

Hence, the SEK is weaker than the Riksbank forecast. Again. Our short-term interest-rate models indicate that EUR/SEK is somewhat overbought (left-hand chart). At the same time rate hikes for 2019 are all but priced out, only 2bp left. One could make the case that the upside in EUR/SEK stemming from interest rate momentum is more limited now (carry remains a SEK headwind, though) and that there is a chance of a correction – risk reward may actually favour a tactical short rather than a tactical long in EUR/SEK. A caveat; the GDP data in two weeks is likely to be a disappointment for the Riksbank. Our new FX forecasts suggest, in line with the rate models, some downside potential in EUR/SEK near term (1M 10.70). Later on EUR/SEK will likely move higher toward 11.00 (12M), not least because the Riksbank will be challenged on its inflation forecast and make it hard to raise the repo rate this year and also next.