There was a very "wonkish" article by Stephen Williamson over the weekend discussing the impact of quantitative easing on inflationary expectations. The article is filled with economic equations discussing interest rates and inflationary expectations but the real crux of the article was:

"In general, if we think that inflation is being driven by the liquidity premium on government debt at the zero lower bound, then if the Fed keeps the interest rate on reserves where it is for an extended period of time, we should expect less inflation rather than more.

But that's not the way the Fed is thinking about the problem. What I hear coming out of the mouths of some Fed officials is that: (i) Things are bad in the labor market, and the Fed can do something about that; (ii) inflation is low. Thus, according to various Fed officials, the Fed can kill two birds with one stone, so it should: (a) keep doing QE; (ii) make it clear that it wants to keep the interest rate on reserves at 0.25% for a very long period of time.

What I hope the discussion above makes clear is that this is a trap for the Fed. There is not much that the Fed can do on its own about the short supply of liquid assets. They can get some action from QE, but the matter is mostly out of their hands, and more QE actually pushes the Fed further from its inflation goal. If the Fed actually wants more inflation, the nominal interest rate on reserves will have to go up. Of course, that will lead to some short-term negative effects because of money nonneutralities."

This is not "new news" for anyone that has either a) been paying attention or; b) reading my posts (see here, here and here) on the deflationary impact of the Fed's "QE" programs. If we set the "math" aside for a moment, and focus on a consumption based economy, it becomes clear that stimulating asset markets will have little effect on economic or labor growth which is ultimately driven by end demand.

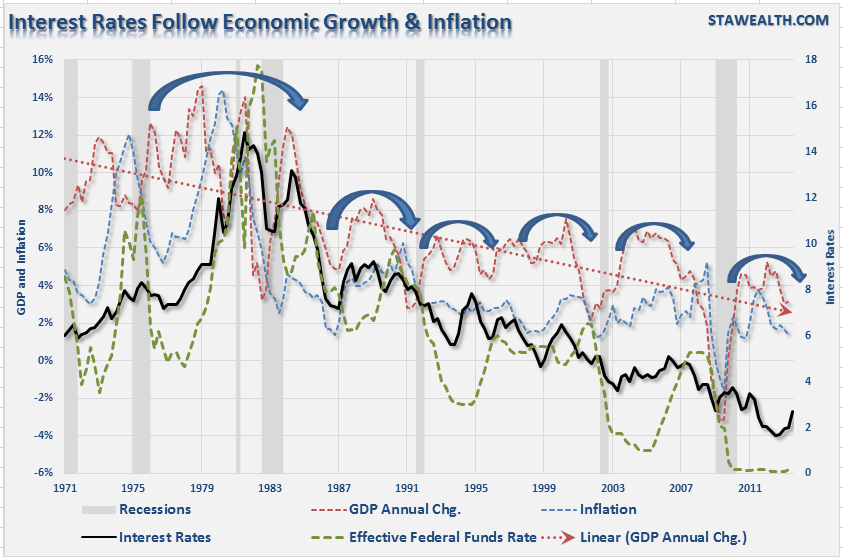

Take a look at the chart below of interest rates, GDP and inflation.

Since 1980 economic growth rates, inflationary pressures and interest rates have all been in a steady decline. This has been due to increased productivity through technological advances which have suppressed wage growth and labor demand. This pressure has become even more rampant since the financial crisis as corporations slash costs to increase profitability while topline revenue has remaind sluggish. During that time the illusion of economic strength have largely been the result of massive increases in debt to fill the gap between slowing rates of income growth and rising living standards.

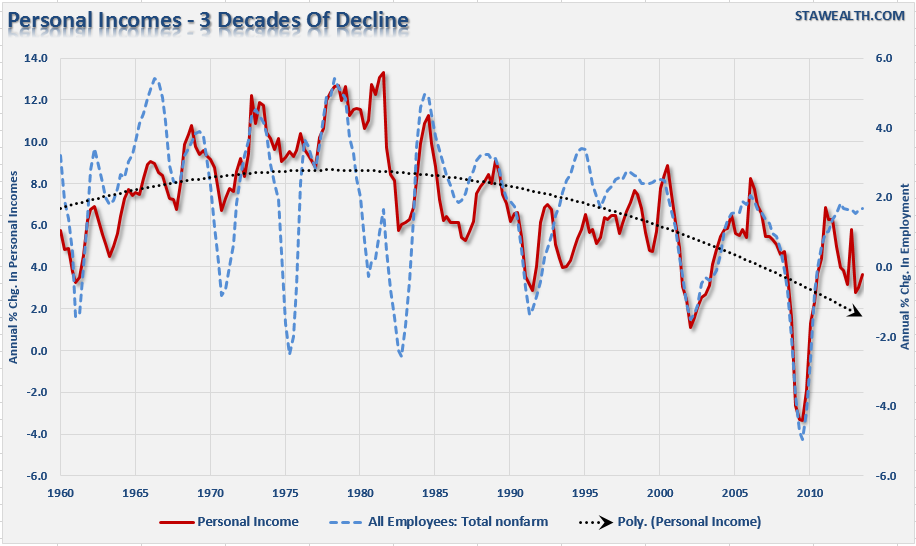

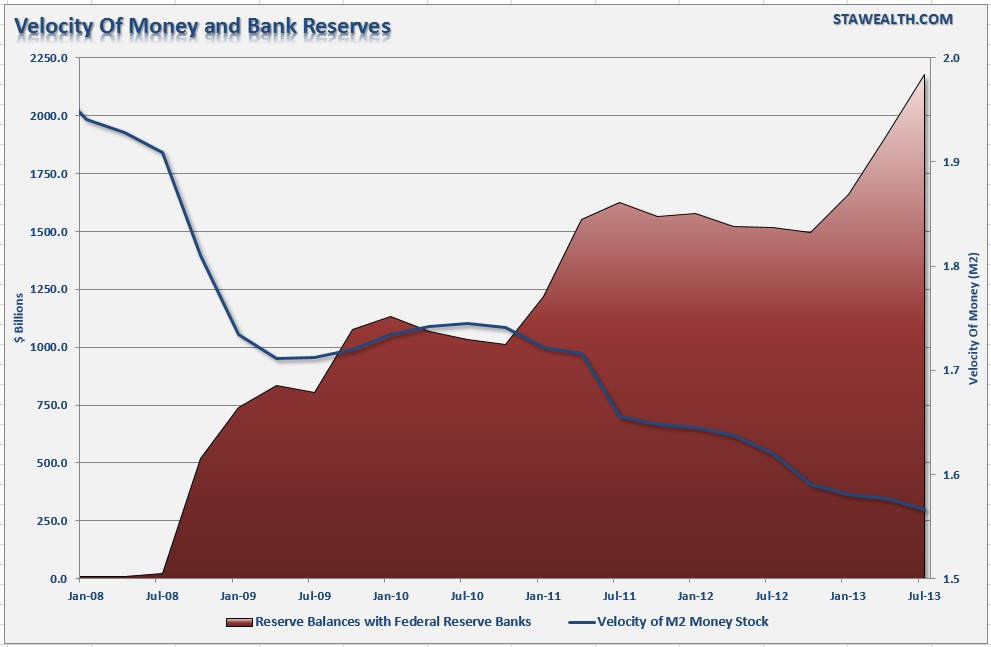

While the Federal Reserve's programs have massively increased the excess reserve accounts of the member banks; those reserves have remained there. This is shown in the chart below and is the result of weak demand for credit in the real economy.

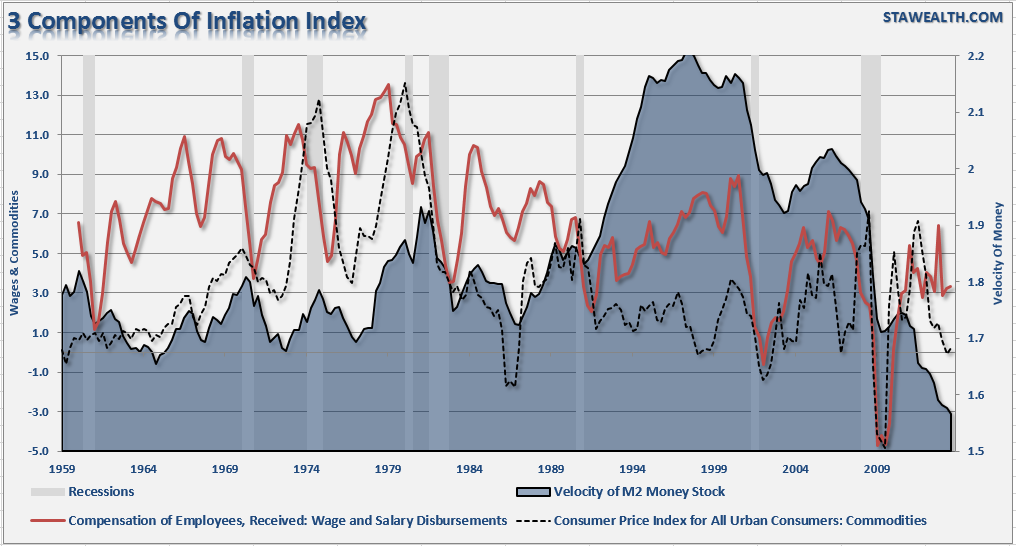

In order for there to be inflationary economic pressures there must be an increase in the demand for credit by businesses to increase production. Increased production results in rising pressures on wages and commodity prices. The chart below shows the real problem for the Fed.

While the Federal Reserve has successfully inflated asset prices; the ongoing interventions have failed to translate from Wall Street to Main Street. A large amount of labor slack has kept wages suppressed which has reduced aggregate end demand keeping pricing power under pressure.

The Federal Reserve's programs certainly assisted in offsetting the risk of the economy falling into a much deeper recession immediately following the financial crisis. The current problem for the Federal Reserve is ceasing programs which are potentially inflating an asset bubble while the economic underpinnings remain to frail to function autonomously.

As Stephen concluded in his article:

"The Fed is stuck. It is committed to a future path for policy, and going back on that policy would require that people at the top absorb some new ideas, and maybe eat some crow. Not likely to happen. The observation of continued low, or falling, inflation will only confirm the Fed's belief that it is not doing enough, not committed to doing that for a long enough time, or not being convincing enough."

The sheer beauty in the Keynesian argument for ongoing monetary interventions is in its simplicity. If the programs work; then the Keynesian model was correct. If the economy fails, or worse, it is only because the Federal Reserve did not do enough. With that kind of logic what could possibly go wrong?

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

QE Deflationary? No Kidding!

Published 12/04/2013, 04:34 AM

Updated 02/15/2024, 03:10 AM

QE Deflationary? No Kidding!

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.