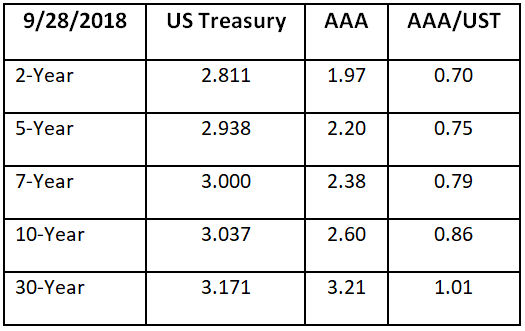

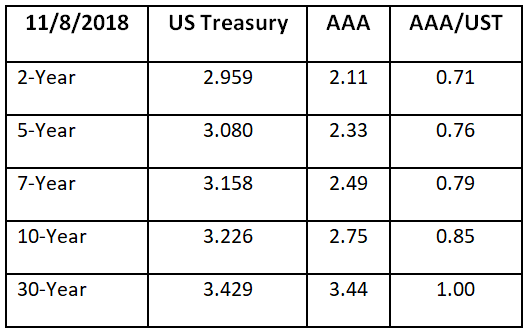

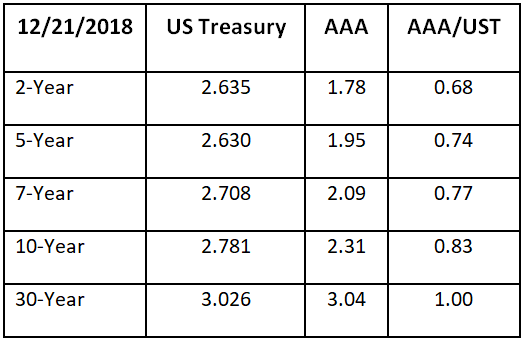

Muni yields rose in the first six weeks of this quarter – mostly in sympathy with US Treasuries (NYSE:UST). We saw the 10-year and 30-year Treasury bonds rise 20 and 25 basis points respectively. Since early November, AAA muni yields (AAA) have dropped across the board, and the 10-year Treasury yield has fallen a whopping 45 basis points in a matter of seven weeks.

The consternation and volatility in the stock market are the main reasons for yields doing a U-turn.

Some of the other themes affecting muni yields we discussed earlier this month:

- The housing market slowdown. Price gains have continued to slow for seven months in a row; and a number of Northeastern states and other previously “hot” markets have seen declines, especially at the higher end of the price range. This falloff is due to a combination of higher mortgage rates earlier this fall plus the specter of higher real estate taxes because of the lack of deductibility in the new tax bill.

- Concern about the rising level of debt and rising government debt service costs (see our piece “November Bond Market Bounce” from December 4).

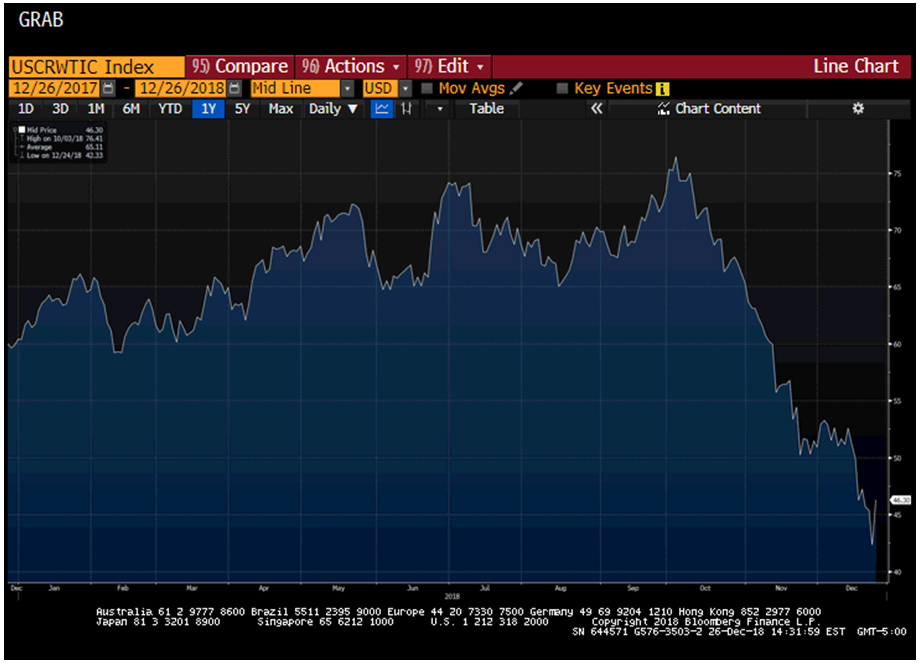

- A general slowdown reflected by the price of oil. See graph below:

West Texas Crude Per Barrel

(Source: Bloomberg)

The freefall in oil suggests that other prices may also be falling, so the combination of HIGHER yields earlier in November and stable-to-falling core CPI certainly made REAL yields seem much more attractive this fall.

Now that yields have fallen, let’s survey the landscape.

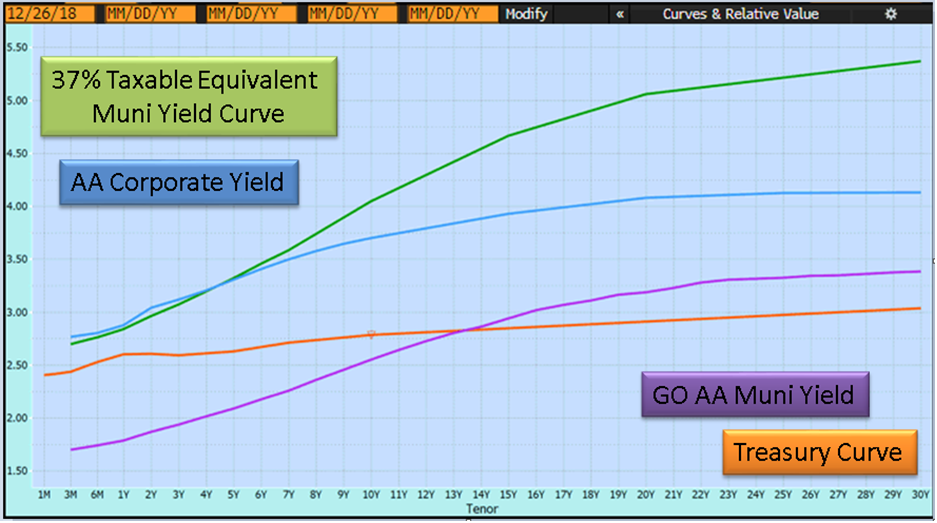

37% Taxable Equivalent

(Source: Bloomberg)

The above graph shows the current muni AA curve and the Treasury yield curve. The curves demonstrate why we have used a barbell strategy, particularly on the tax-free side, where longer muni yields are CHEAPER than Treasuries yields. We believe those high yield ratios on the longer-maturity spectrum eventually go back to 100% or under – this outcome would be consistent with other Federal Reserve hiking cycles. For spread purposes we have also included a AA corporate bond yield curve and created a taxable-equivalent muni yield curve using the current top tax rate of 37%. This comparison demonstrates the advantage of munis over Treasuries for any level of taxpayer and the additional advantage of tax-free munis over corporates for high-tax payers, in the five-year tenor and beyond. The much lower default experience of munis versus corporates simply stretches this advantage.

The Federal Reserve last week raised the fed funds target yield range ¼% to 2.25%–2.5%.

The Fed also made mention of two possible increases next year and did so with less flexibility in the language, which helped to spook the equity market after the announcement last Wednesday. Our thoughts are that if core inflation remains where it has been, at 2.0–2.25% and if there are more Fed hikes next year, the Fed will finally have gotten Fed funds to a positive spread over core inflation – where it has not been for 10 years. That would appear to be a good place for the Fed to pause. And as we get to that pause, we will begin to pick up the pace of moving very-low-duration assets out somewhat further on the yield curve to lock in rates, as shorter to intermediate rates most likely slowly work their way down.

Happy New Year to all our readers!