Too much time and talk is being devoted to when the Fed will make its first Fed Funds rate increase in many years, while too little time and talk is being devoted to how to position for it.

Let’s talk about Treasury bonds as they relate to a future Fed Rate increase, whether it happens next week, in a few months, or later.

Before we do that, let’s look at corporate bonds, which we don’t think are particularly attractive in the short-term.

Corporate profits overall are recently flat to slightly down; with concerns about:

- what impact a Fed Funds rate increase may have;

- possible further strengthening of the dollar to the detriment of corporate earnings

- fears (we think not well founded so far) of a global recession induced by China or something else.

Those and similar thoughts have resulted in the yield spread between corporate bonds and similar maturity Treasuries to widen. That puts downward price pressure on corporate bonds relative to Treasury prices.

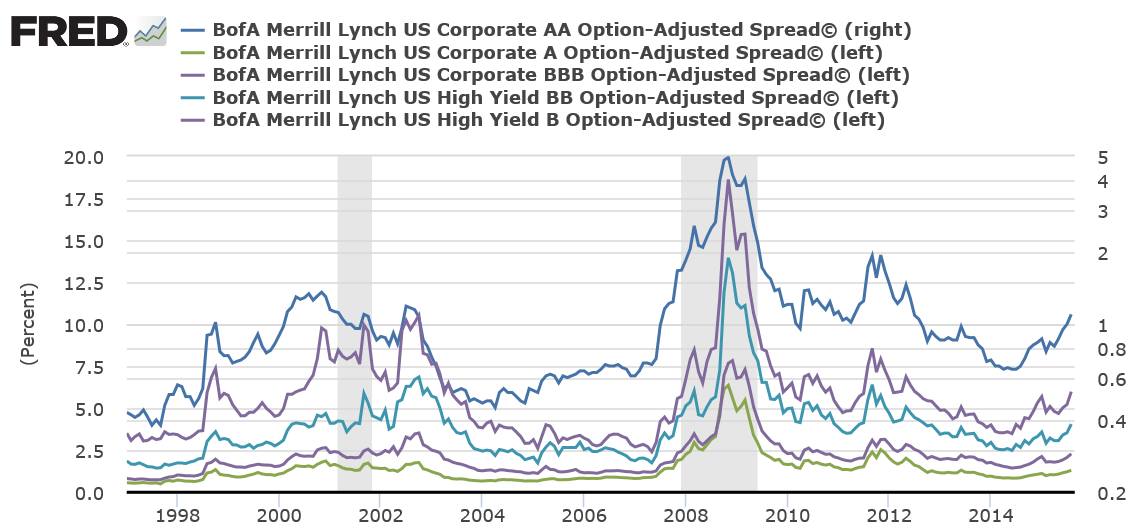

Figure 1 shows the “credit spreads” for corporate bonds of various quality levels — the spreads are rising — reducing the appeal of corporate bonds except for the highest quality.

FIGURE 1:

Bill Gross in his September letter likes cash or 1-2 year corporate bonds best at this time:

“High quality global bond markets offer little reward relative to durational risk. …Cash or better yet “near cash” such as 1-2 year corporate bonds are my best idea of appropriate risks/reward investments. The reward is not much, but as Will Rogers once said during the Great Depression – “I’m not so much concerned about the return on my money as the return of my money.”

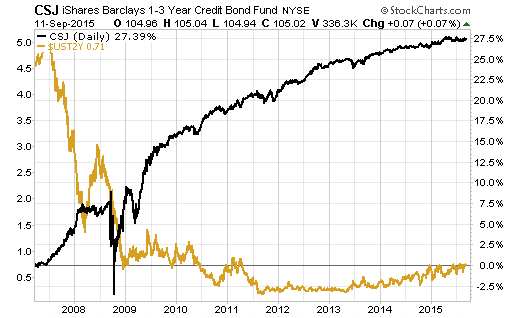

For those looking to follow Bill Gross’s opinion for cash or 1-2 year credit bonds, cash is an easy solution; and two investment grade corporate bond ETFs with 2-year average maturities from major sponsors might fit the Gross’s corporate bond idea: (NYSE:CSJ) (iShares) and (NYSE:SCPB) (SPDRs).

Figure 2 is a price performance chart of CSJ (trailing yield 1.04% ) versus the 2-year Treasury yield (current yield 0.71%):

FIGURE 2:

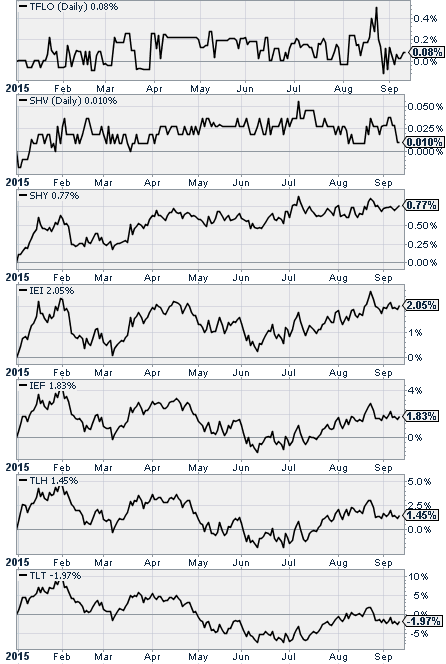

Rates are more abstract that bond prices. Figure 3 shows the year-to-date distribution adjusted prices for readily investable corporate bond funds:

- Vanguard Short-Term corporates (NASDAQ:VCSH),

- Vanguard Intermediate-Term corporates (NASDAQ:VCIT),

- Vanguard Long-Term corporates (NASDAQ:VCLT),

- Ishares High Yield corporates (NYSE:HYG).

We don’t see anything enticing there, particularly after-tax and inflation. The short-term bonds did best so far this year.

FIGURE 3:

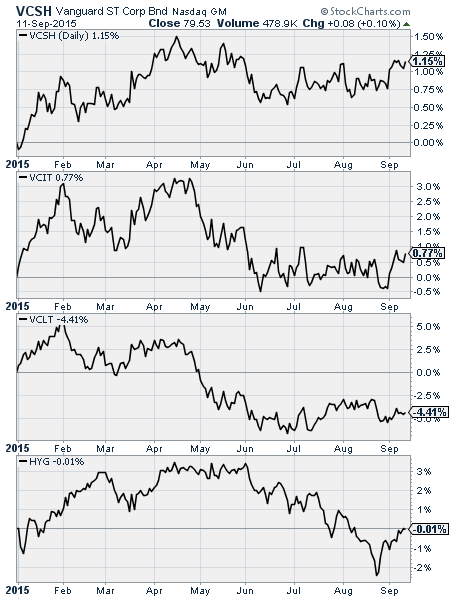

Looking at corporate bond fund performance versus Treasury bond fund performance, Figure 4 shows short-term corporate bonds a bit ahead of short-term Treasuries, but intermediate-term and long-term corporates behind Treasuries.

It divides the performance of the three Vanguard corporate bond funds in Figure 3 by the performance of these Vanguard government bond funds:

- Vanguard Short-Term governments (NASDAQ:VGSH),

- Vanguard Intermediate-Term governments (NASDAQ:VGIT)

- Vanguard Long-Term governments (NASDAQ:VGLT).

FIGURE 4:

Now on to Treasuries and the Fed.

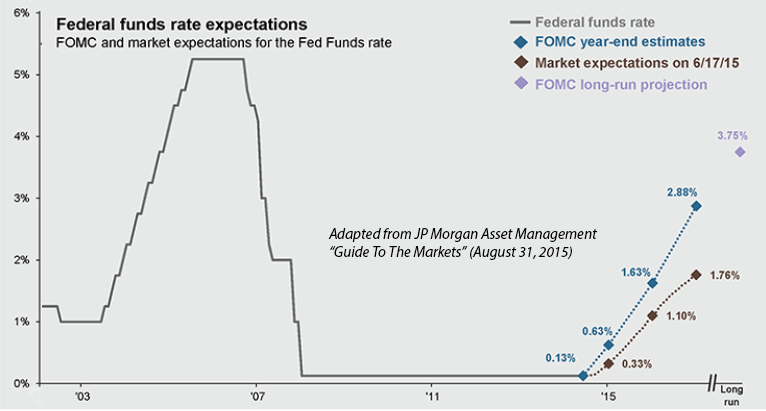

Figure 5 is adapted from JP Morgan Asset Management, “Guide to the Markets” (August 31, 2015) shows the history of the Fed Funds rate since the stock market bottom in 2003 through now, plus the forecasts by the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee and by market participants.

It shows significantly rising rates over several stock Bull market years beginning in 2003. It also shows forecasted Fed Fund rates increasing in small increments over a few years to levels which were not problematic for stocks in the past cycle.

FIGURE 5:

But what about the impact on other Treasury rates (and Treasury bond funds)?

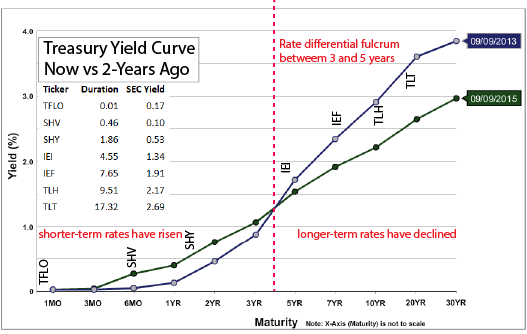

Figure 6 (adapted from a yield curve chart from the Federal Reserve) shows the Treasury rates over the range of maturities (the “yield curve”) for September 9, 2015 in comparison to the curve from 2 years prior on September 9, 2013.

The key observations are that 4-year Treasuries (they don’t issue 4-year Treasuries, but a 5-year bond 1 year after issue is a 4-year bond) have been the fulcrum of rate change — with longer rates declining and shorter rates rising.

Readily investable Treasury ETFs are displayed on the curve. Their placement is approximate because we have the duration for the funds (shorter than maturity) and the maturity of the Treasuries. It’s probably close enough for illustrative purposes, particularly at the shorter matures.

- BlackRock: The ETFs on the chart are from BlackRock iShares: TFLO (ultra-short-term, floating rate Treasuries), (NYSE:SHV)

- State Street: A similar but less granular set of ETFs from State Street SPDRs (not shown) are (NYSE:BIL) (1-3 mo Treasuries), (NYSE:SST) (short-term Treasuries), (NYSE:ITE) (intermediate-term Treasuries) and (NYSE:TLO) (long-term Treasuries).

- Vanguard: The Vanguard ETF set used in Figure 4 also provide low granularity Treasury options: (NASDAQ:VGSH) (short-term), (NASDAQ:VGIT) (intermediate-term) and (NASDAQ:VGLT) (long-term).

FIGURE 6:

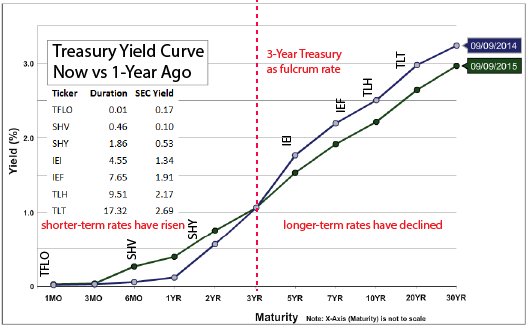

Figure 7 is set up the same way as Figure 6, but compares the yield curve from now to 1 year ago instead of 2 years ago. The fulcrum point has shifted down from 4 years to 3 years, but otherwise the situation is about the same — shorter rates higher and longer rates lower.

FIGURE 7:

The TFLO fund (a floating rate Treasuries fund) has a duration close to zero, meaning it should have minimal price impact from the Fed Fund rate — rather than a price decline, one would expect a yield increase — very small yield to be sure, but an increase nonetheless. The current yield is17 basis point, but would likely rise to around 40 basis points, when/if the Fed Funds rate rises by 25 basis points.

We don’t have the data, or experience, or wisdom of Bill Gross (hardly anybody does), but from the limited view of these data above, it would seem that (at least for Treasuries) the 3-5 year range might be a bit safer than shorter periods — at least for the next 1-6 months.

If 3-5 year maturities are the fulcrum when the Fed Funds rate rises, then unless the entire yield curve shifts up in a parallel sort of shift, those maturities might experience the least yield change. At the same time, the shorter maturity Treasuries are more prone to yield adjustment upward (price down).

As for the longer-term maturities, if inflation is not of great concern, and if China induced recession is a continuing fear, and if the Dollar strengthens, then maybe a flow of investments would stabilize if not reduce those longer-term rates. That however is a speculative possibility, less predictable than that there may be a relatively stable yield maturity fulcrum for which there is some actual data.

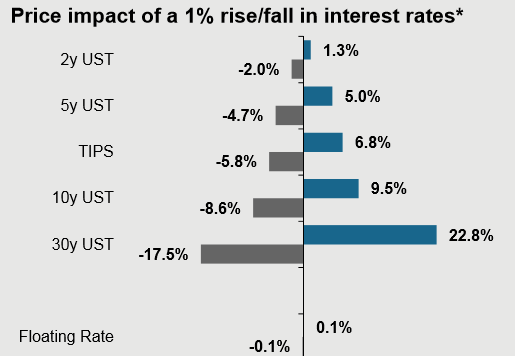

Figure 8 from JP Morgan Asset Management forecasts the price impact of a 1% yield change at each maturity level (not 1% increase across the entire curve at one time, but if and when each maturity experiences a 1% yield change). That is based on some well test math called the “Macaulay duration” formula.

That Macaulay formula is for a quantum change in yields. If it happens over an extended period, the duration of any particular bond will have shortened by the passage of time, thus reducing somewhat the price impact of each step in the yield increase.

Based on the FOMC and market participants forecasts of the Fed Funds rate rising by about 25 basis points sometime soon, as supposing that the 2-year Treasury maintains its current yield spread to the Fed Funds rate, then Figure 8 suggests something like a 0.5% price reduction in that 2-year Treasury at the first Fed Funds rate increase. If the yield cure flattens a bit and the yield spread is not maintained, then less than a 0.5% price decline would be expected.

Will the fulcrum hold? Nobody knows for sure, but it has been relatively stable for 2 years with a lot of rates other than the Fed Funds rate gyrating.

FIGURE 8:

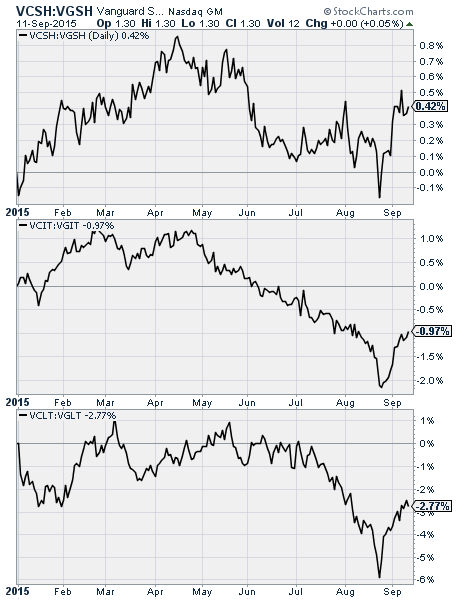

Figure 9 shows the daily distribution adjusted price changes for each of the iShares Treasury ETFs we saw in the two yield curve charts (Figures 6 and 7).

(NYSE:SHY) (the 1-3 year / 1.86 year average duration / 1.85 year average maturity Treasury ETF) has the most stable performance of the lot.

(NYSE:IEI) (3-7 year / 4.55 year average duration / 4.78 year average maturity) was more volatile, but with better total return.

FIGURE 9:

Overall, we have “Fed fatigue”. How about you? Let’s get over it and make a nominal increase so we can move on to other sources or worry.

Let’s face it, bonds don’t do much for investors at this time. Cash has price stability, but also has inflation risk (and currency exchange risk). After tax and after inflation on the yield net of tax, there really isn’t much more benefit than cash in short-term bonds, and bonds have price variability, particularly now.

Longer-term bonds have better after-tax, after inflation yield but much higher price sensitivity to Treasury rates.

Overall, for the next few months, we prefer cash to bonds for tactical reasons.

Some of our customers chose to hold bonds right now, but most do not, However, most hold significant tactical cash. Those who do hold bonds are in corporate bonds, light on the shorter-term and light on the longer-term, staying somewhere in the lower middle of the curve.