Since the passage of “tax cuts,” in late 2017, the surge in corporate share buybacks has become a point of much debate. As I previously wrote, stock buybacks are once again on pace to set a new record in 2019. To wit:

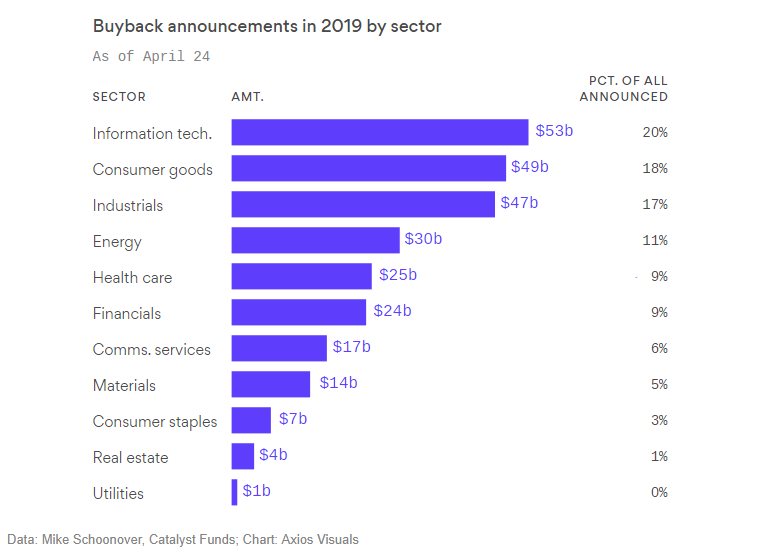

“A recent report from Axios noted that for 2019, IT companies are again on pace to spend the most on stock buybacks this year, as the total looks set to pass 2018’s $1.085 trillion record total.”

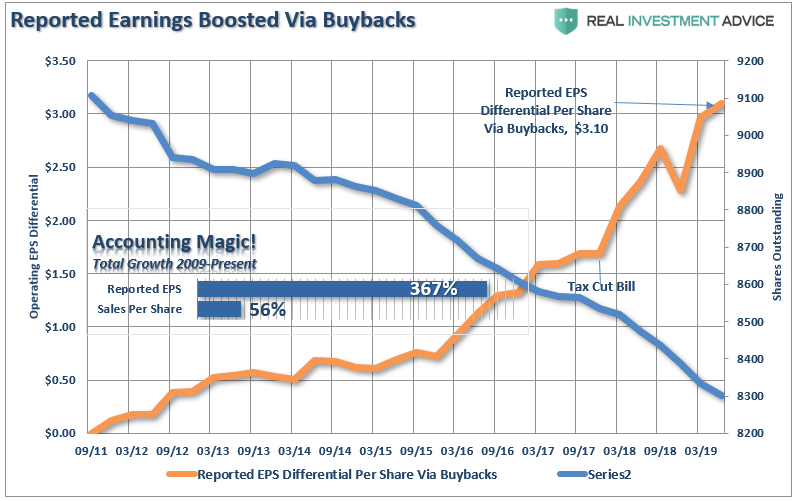

The reason companies spend billions on buybacks is to increase bottom-line earnings per share which provides the “illusion” of increasing profitability to support higher share prices. Since revenue growth has remained extremely weak since the financial crisis, companies have become dependent on inflating earnings on a “per share” basis by reducing the denominator.

“As the chart below shows, while earnings per share have risen by over 360% since the beginning of 2009; revenue growth has barely eclipsed 50%.”

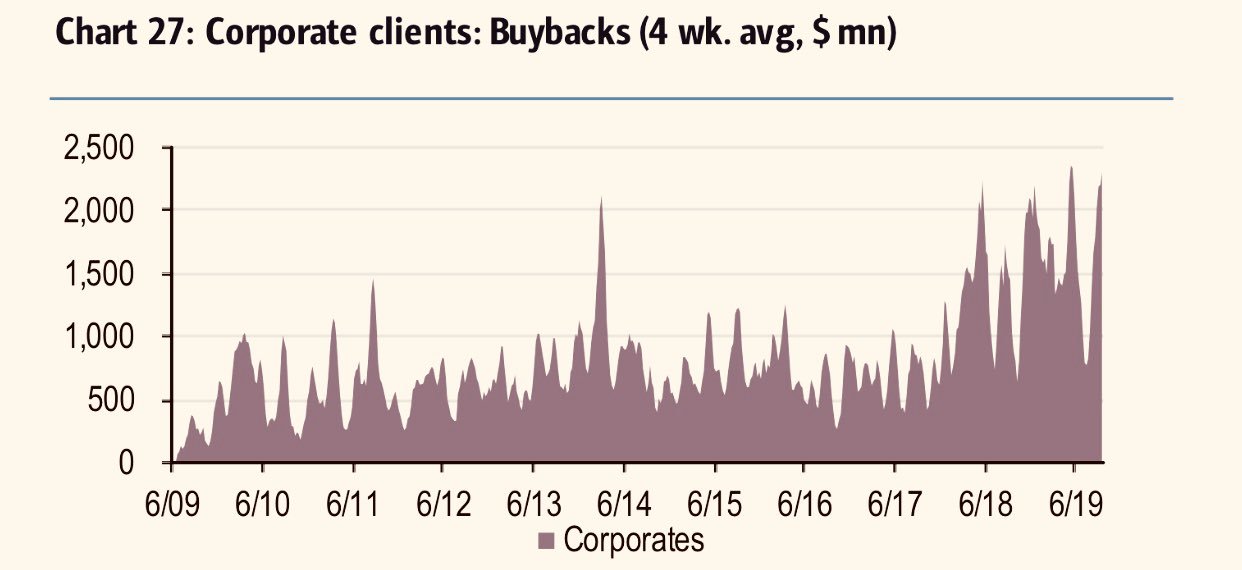

As shown by BofA, in 2019, cumulative buybacks are up +20% on an annualized basis, with the 4-week average reaching some of the highest levels on record. This is occurring at a time when earnings continue to come under pressure due to tariffs, slower consumption, and weaker economic growth.

While share repurchases are not necessarily a bad thing, it is just the “least best” use of companies liquid cash. Instead of using cash to expand production, increase sales, acquire competitors, make capital expenditures, or buy into new products or services which could provide a long-term benefit; the cash is used for a one-time boost to earnings on a per-share basis.

Yes, share purchases can be good for current shareholders if the stock price rises, but the real beneficiaries of share purchases are insiders where changes in compensation structures have become heavily dependent on stock-based compensation. Insiders regularly liquidate shares which were “given” to them as part of their overall compensation structure to convert them into actual wealth. As the Financial Times recently penned:

“Corporate executives give several reasons for stock buybacks but none of them has close to the explanatory power of this simple truth: Stock-based instruments make up the majority of their pay and in the short-term buybacks drive up stock prices.”

That statement was further supported by a study from the Securities & Exchange Commission which found the same issues:

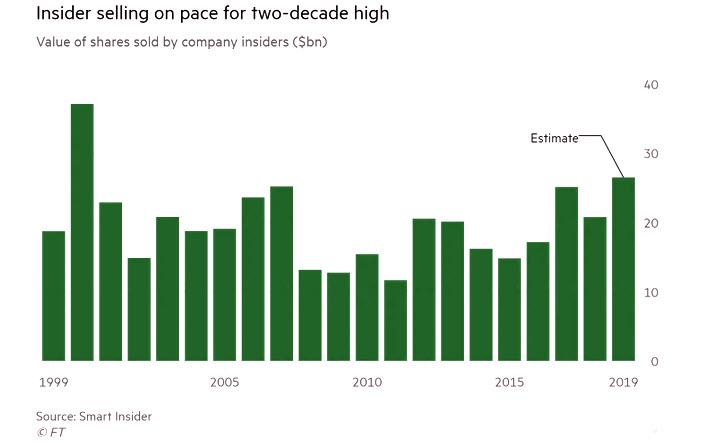

Not surprisingly, as corporate share buybacks are hitting record highs; so is corporate insider selling.

What is clear, is that the misuse, and abuse, of share buybacks to manipulate earnings and reward insiders has become problematic. As John Authers recently pointed out:

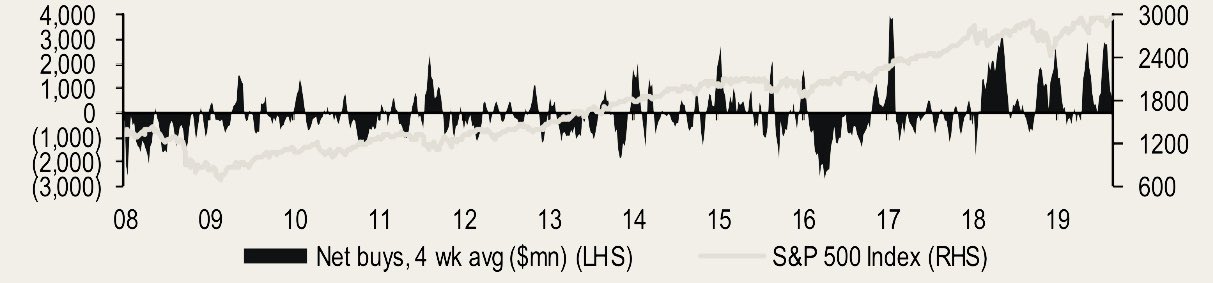

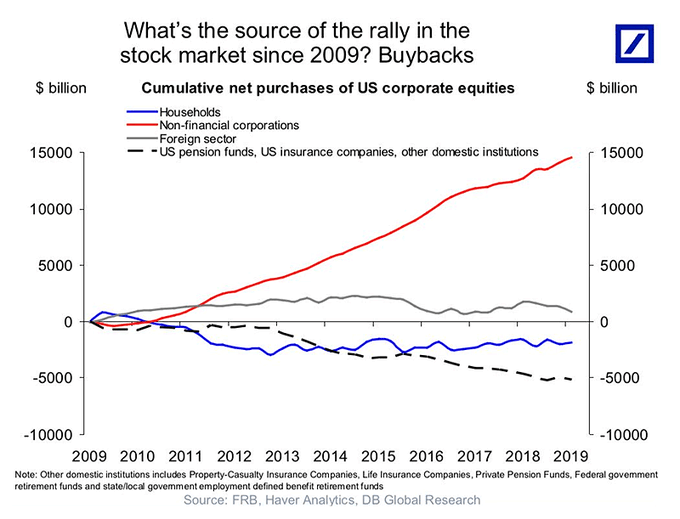

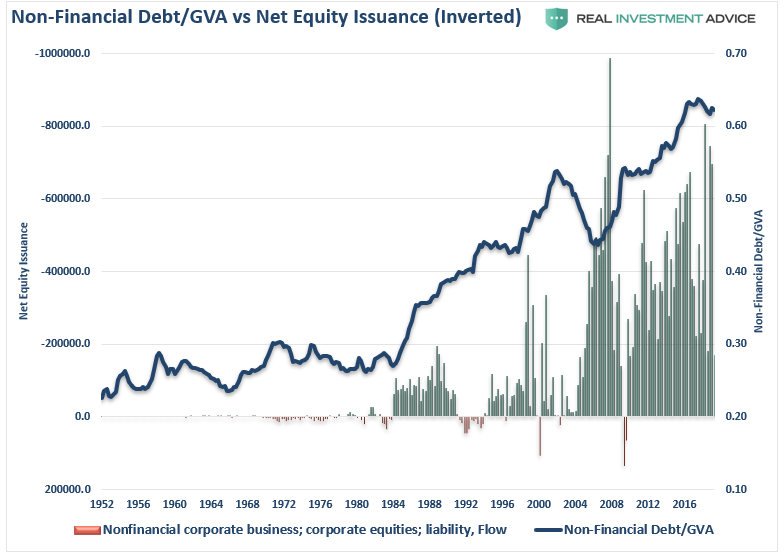

“For much of the last decade, companies buying their own shares have accounted for all net purchases. The total amount of stock bought back by companies since the 2008 crisis even exceeds the Federal Reserve’s spending on buying bonds over the same period as part of quantitative easing. Both pushed up asset prices.”

In other words, between the Federal Reserve injecting a massive amount of liquidity into the financial markets, and corporations buying back their own shares, there have been effectively no other real buyers in the market.

Less Bang For The Buck

While investors have chased asset prices higher over the last couple of years on hopes of a “trade deal,” more accommodation from Central Banks, or hope the “bull market will never end,” the impact of share buybacks on asset prices is fading.

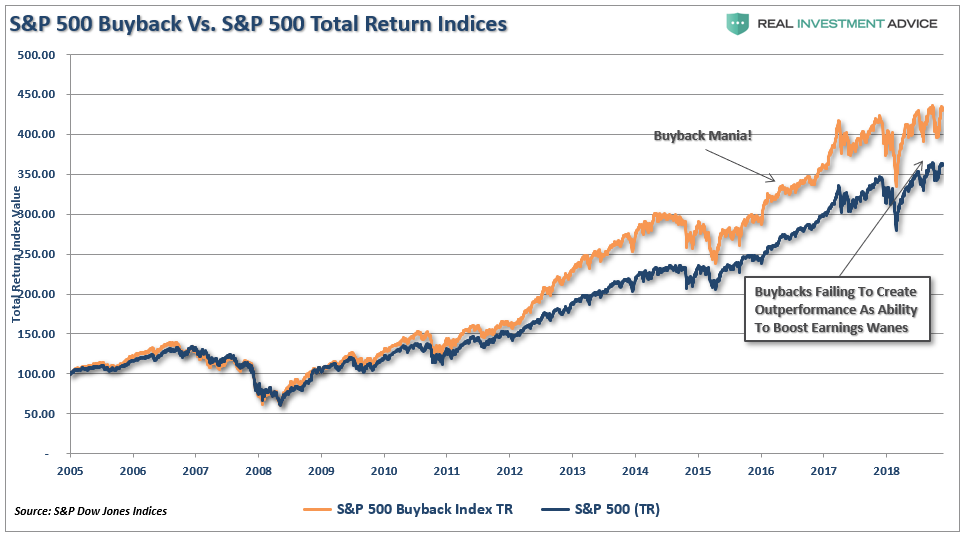

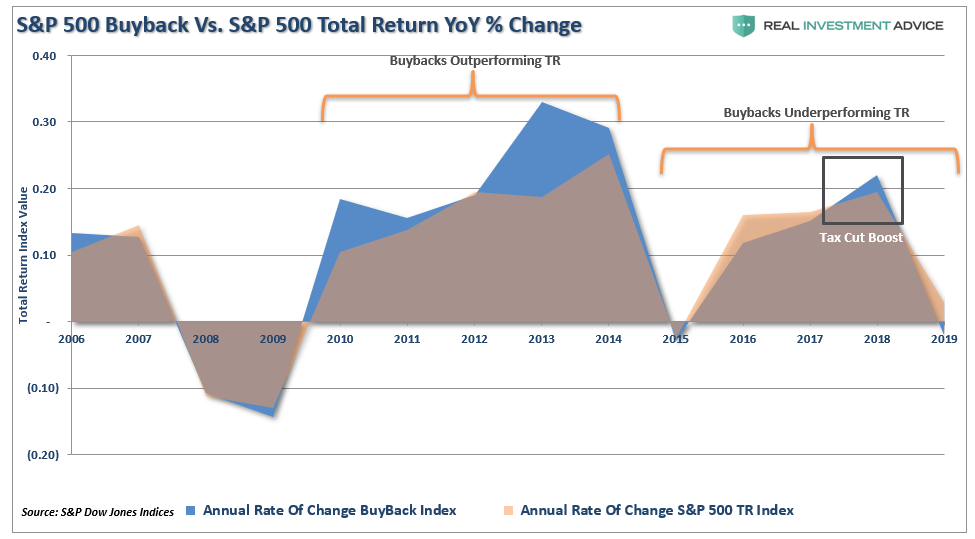

The chart below is the S&P 500 Buyback Index versus the Total Return index. Following the financial crisis, when companies changed from “splitting shares” to “reducing shares,” there has been a marked outperformance by those companies.

However, while corporate buybacks have accounted for the majority of net purchases of equities in the market, the benefit of pushing asset prices higher is waning. Outside of the brief moment in 2018 when tax cuts were implemented, which allowed companies to repatriate overseas cash, the buyback index has underperformed.

Without that $4 trillion in stock buybacks, not to mention the $4 trillion in liquidity from the Federal Reserve, the stock market would not have been able to rise as much as it has. Given high valuations, weakening earnings, and sluggish economic growth, without continued injections of liquidity going forward, the risk of a substantial repricing of assets has risen.

A more opaque problem is that share repurchases have increasingly been done with the use of leverage. The ongoing suppression of interest rates by the Federal Reserve led to an explosion of debt issued by corporations. Much of the debt was not used for mergers, acquisitions or capital expenditures but for the funding of share repurchases and dividend issuance.

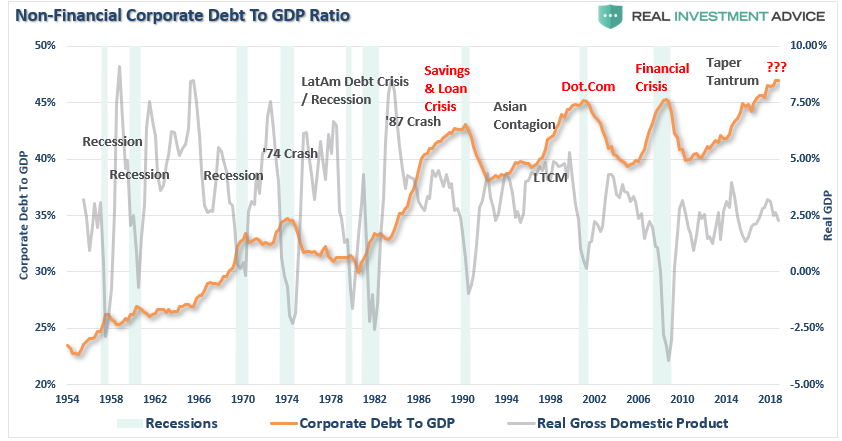

The explosion of corporate debt in recent years will become problematic during the next bear market. As the deterioration in asset prices increases, many companies will be unable to refinance their debt, or worse, forced to liquidate. With the current debt-to-GDP ratio at historic highs, it is unlikely this will end mildly.

This is something Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan warned about:

U.S. nonfinancial corporate debt consists mostly of bonds and loans. This category of debt, as a percentage of gross domestic product, is now higher than in the prior peak reached at the end of 2008.

A number of studies have concluded this level of credit could ‘potentially amplify the severity of a recession,’

The lowest level of investment-grade debt, BBB bonds, has grown from $800 million to $2.7 trillion by year-end 2018. High-yield debt has grown from $700 million to $1.1 trillion over the same period. This trend has been accompanied by more relaxed bond and loan covenants, he added.

It’s only a problem if a recession occurs.

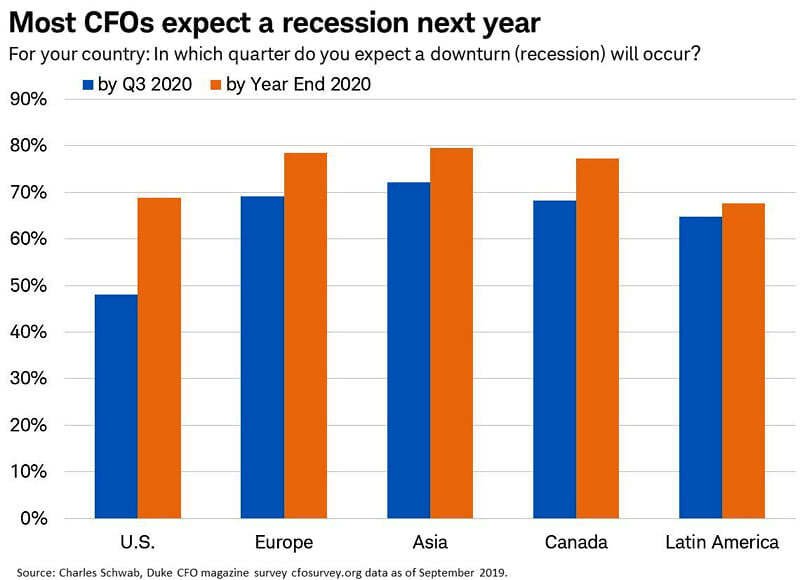

“According to CNN,53 percent of chief financial officers expect the United States to enter a recession prior to the 2020 presidential election. That information was sourced from the Duke University/CFO Global Business Outlook survey released on Wednesday. And two-thirds predict a downturn by the end of next year. While a slight downturn may not amount to a recession, it certainly means CFOs are taking the initiative to prepare for the worst.”

This is a very important point.

CEO’s make decisions on how they use their cash. If concerns of a recession persist, it is likely to push companies to become more conservative on the use of their cash, rather than continuing to repurchase shares. If that source of market liquidity fades, the market will have a much tougher time maintaining current levels, or going higher.

Summary

While share repurchases by themselves may indeed be somewhat harmless, it is when they are coupled with accounting gimmicks and massive levels of debt to fund them in which they become problematic.

The biggest issue was noted by Michael Lebowitz:

“While the financial media cheers buybacks and the SEC, the enabler of such abuse idly watches, we continue to harp on the topic. It is vital, not only for investors but the public-at-large, to understand the tremendous harm already caused by buybacks and the potential for further harm down the road.”

Money that could have been spent spurring future growth for the benefit of investors was instead wasted only benefiting senior executives paid on the basis of fallacious earnings-per-share.

As stock prices fall, companies that performed un-economic buybacks are now finding themselves with financial losses on their hands, more debt on their balance sheets, and fewer opportunities to grow in the future. Equally disturbing, the many CEO’s who sanctioned buybacks, are much wealthier and unaccountable for their actions.

For investors betting on higher stock prices, the question is whether we have now seen “peak buybacks?”