- Understand the difference between calls and puts

- Learn the rights and obligations of buying and selling call and put options

- Understand the risk and reward profiles of long and short calls and put options positions

Options give traders, well, options. But options aren’t just for traders; qualified investors can trade options too. Investors can use options to manage risk and try to potentially enhance returns. Options aren’t suitable for everyone, however, because they can involve significant risks.

Options are typically used to speculate on the direction of the market, hedge against market downturns, or pursue an additional income goal. This is why many active traders add them to their strategy toolbox.

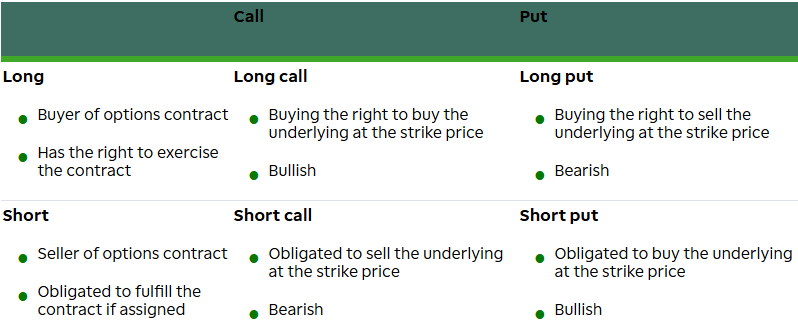

First, the basics. There are two types of options: calls and puts. Each has its benefits and risks, and they change depending on if you’re the buyer or seller.

What Are Calls and Puts?

Calls are options that give a trader the right, but not the obligation, to buy an “underlying” asset like a stock or index. So, when buying a call option, a trader has the right to buy the underlying stock or index. When selling a call option, a trader assumes the obligation to supply the underlying asset when and if the call contract is assigned (more on this later).

So, what is a put? A put option gives a trader the right to sell the underlying stock or index. The put buyer obtains the right to sell the underlying stock or index, while the put seller assumes the obligation to buy the underlying asset when and if the put option is assigned.

Let’s look at how to go about buying a call and put options. We’ll start with calls.

Buying a Call: The Coupon Analogy

Suppose a trader is interested in buying a stock, but maybe they don’t want to buy it outright for whatever reason. Instead of buying the shares, they might consider buying a call option that gives them the right to buy the shares on or before a later day (expiration) at a specified price (strike price). So even though they don’t own the shares, they get to “control” a certain number of shares. This gives them the potential to profit (or lose) if the stock makes a move. If the stock moves down, stays the same, or doesn’t go up much, the trader will likely incur a loss in the amount paid for the call option (premium) plus transaction costs.

So before placing an options trade, traders should consider the number of contracts they’re going to trade, the expiration date, the strike price, and the cost of the contract (premium). You can access all this from the Option Chain on the thinkorswim® platform (see figure 1).

Chart source: The thinkorswim platform

FIGURE 1: OPTION CHAIN. On the thinkorswim platform, from the Analyze or Trade tab, you can access the Option Chain for different options contracts and identify the strike prices and cost of each.

Buying a call option is kind of like buying a coupon at a discount. Say you pay $25 for a coupon that entitles you to a $50 Kobe beef steak dinner. However, suppose new trade restrictions and tariffs on Japanese beef have recently caused the regular price of the dinner to rise to $55. The coupon is now intrinsically worth more. Although you’re still entitled to the same steak dinner, its value has risen by $5, from $50 to $55. This opens up some choices for you. Suppose your brother-in-law is interested in using the coupon for date night and offers you $30 for your coupon. Do you keep it or sell it? If you keep the coupon, you run the risk of losing the entire $25 you paid for it.

For example, imagine there’s been a huge influx of Kobe beef to the United States. The high supply of beef caused steak dinner prices to tumble, and the restaurant is now offering the same steak dinner for $20. Your coupon is now worthless because the price of the dinner on the open market is lower than the price you paid for the coupon.

Like the dinner coupon, an options contract derives its value from the underlying instrument. That’s why options are included in a subset of financial instruments called derivatives.

The coupon example illustrates that buying a call is a bullish strategy because it can profit if the underlying product rises in value. If a trader is bullish on a stock, they could choose to buy a call. But a call option depreciates in value as time passes. Almost every day, options time value shrinks (the greek “theta” measures this erosion) until it expires. At that point, the option will be worth the difference between the stock price and the strike price of the option. Your call option may have some value if the stock price is higher than the strike price of the call, or it may be worthless if the stock price is at or below the strike price.

Selling a Call

What if you decide to sell a call?

Are options the right choice for you?

While options trading involves unique risks and is definitely not suitable for everyone, if you believe options trading fits with your risk tolerance and overall investing strategy, TD Ameritrade can help you pursue your options trading strategies with powerful trading platforms, idea generation resources, and the support you need.

Learn more about the potential benefits and risks of trading options.

As the seller of a call option, a trader is bearish or at least neutral on the underlying stock because they’re predicting the stock will remain below the strike price on expiration.

But depending on the call option sold, a trader doesn’t have to be super bearish. In fact, they can be relatively neutral. Do you remember how we said that the time value of an option depreciates? Well, as a call seller, the depreciation can work in their benefit. If selling a call that obligates the owner to deliver stock shares at $50, as long as the stock price stays below $50, they likely won’t have to deliver shares. This agreed-upon price is the strike price—that’s the price at which the transaction was “struck.” However, there’s still a chance the trader could be assigned at any time, even if the stock price is below the strike price.

It’s also important to consider whether the trader already owns the underlying stock. If so, it’s known as a “covered call,” and if assigned, the trader would be required to sell their shares at the strike price. If they don’t own the shares (called a “naked call”) and are assigned, they’d have a resulting short stock position and would need to buy back the shares in the open market to close the position. They could also consider holding them as a short position.

When selling a call option, credit is received. This credit is the trader’s to keep no matter what happens. But this doesn’t mean they’ll profit no matter what happens. If the stock rallies above the strike price, they’re obligated to deliver the shares at the strike price. If they don’t own the shares, they’ll have to either buy them at the higher (current market) price or hold a short position on the stock. And, theoretically, a stock price could climb forever, so there’s unlimited risk with this strategy.

If a trader does have the shares in their account (a “covered call”), then they would’ve missed out on any stock price movement above the strike price. Under normal conditions, they could attempt to buy back the option or roll it to another strike or delivery month. This may result in a smaller profit than the credit, or even a loss, and will incur additional transaction costs.

So, remember, if a trader is bullish, they could buy a call. If they’re bearish or neutral, they could sell a call. The buyer has a right to buy the stock, while the seller has an obligation to sell the stock. Finally, remember that options erode in value as time passes, which can benefit the seller but hurt the buyer.

Buying and Selling Put Options

Suppose a trader owns shares of a stock and believes the stock’s price is going to fall. They could buy a put, which locks in a sale price for a limited time. A put allows the trader to sell their stock at a set price—the strike price—so that if the stock price falls, they can exercise the put contract. If they don’t own the stock, buying a put is more speculative in nature, typically based on a prediction that the stock price will fall. Puts increase in value as the underlying stock price falls. But remember, as time passes, calls and puts depreciate in time value. And, if the stock price moves higher, the value of a put typically falls.

When selling a put, a trader is bullish. Of course, depending on which strike price is chosen, they could be bullish to neutral. Some traders may simply want the stock price to stay above the strike price and the put’s value to decline, eventually expiring worthless.

If the underlying stock price falls below the strike price, they’ll likely be required to buy the stock shares at the strike price. This could require a substantial amount of money. If it’s a stock they’d like to own, then selling puts can be one way to attempt to buy it at a lower price than the current market while generating a credit. But of course, they have to make sure they have sufficient funds in the account to purchase and maintain the shares. And keep in mind, the stock price could continue to fall, resulting in a loss.

Four Primary Options Strategies

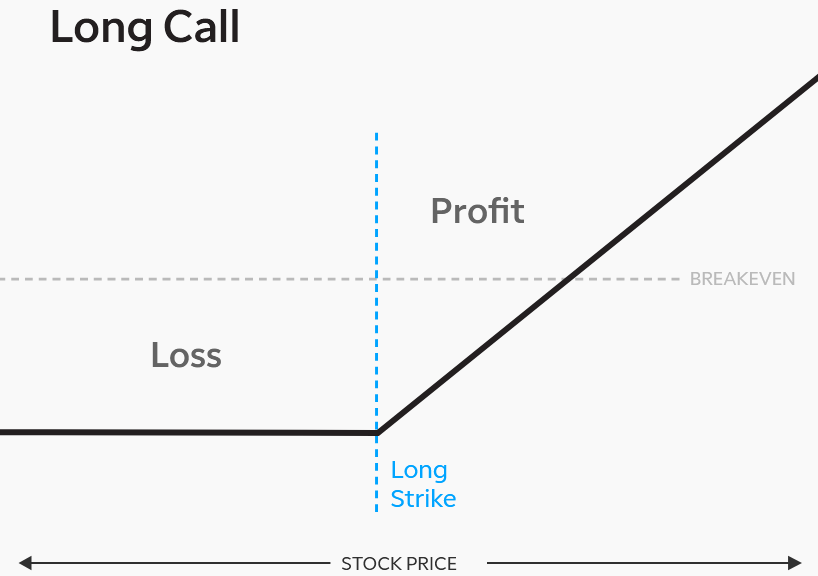

Long Call

An options contract that gives the buyer the right to buy shares of stock at a certain price (strike price) on or before a particular day (expiration day). For illustrative purposes only.

Here’s a brief summary of how it all fits together: calls and puts, selling and buying calls versus puts, and bullish and bearish biases.

The Up (and Down) Shot

So now we’ve covered some basic concepts of call and put options—their definitions, differences, and how both work. We’ve demonstrated some benefits and risks of buying options versus selling options. However, this article only scratches the surface in terms of options strategies. But be sure you’re familiar with these basic strategies for buying and selling call and put options before moving on to more advanced strategies.

Disclosure: TD Ameritrade® commentary for educational purposes only. Member SIPC. Options involve risks and are not suitable for all investors. Please read Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options.