The key risk of the Trump Presidency, namely a global trade war, has risen markedly in recent weeks. With the US imposing a series of unilateral tariffs and the countries affected quickly responding in kind, the opening shots have been fired. The fear is that the relatively small measures so far announced are simply the opening salvos of a much larger war.

Until recently, financial markets had shrugged off the risk of a trade war. Optimism was based on three key assumptions. First, it was hoped that President Trump was essentially bluffing and the threat of tariffs was largely a negotiating tool to help re-jig existing trade deals. Second, even if the President wanted to follow through on his threats, cooler heads in the administration would tend to restrain him. Third, it was assumed that the self-defeating nature of a trade war would soon become apparent, working against any significant escalation.

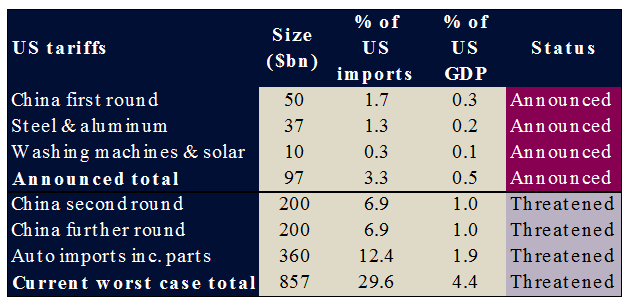

All of these assumptions now look questionable. A string of measures have already been announced, with more threatened. The table below provides a taxonomy of actual and threatened US measures so far. Hopes that the President’s key economic advisors would restrain him also look increasingly forlorn. Finally, the current rude health of the US economy, enjoying near record low unemployment and strong economic growth, is emboldening President Trump to take greater risks.

Source: QNB Economics

The shots fired so far are barely sufficient to give the US economy a flesh wound. The US’s total import bill was $2.34 trillion in 2017 while its GDP was a huge $19.4 trillion. The tariffs so far announced of close to $100 billion therefore only cover a little more than 3% of the US’s import bill,or around 0.5% of GDP. Retaliatory measures have been tit-for-tat with China responding with $50bn of tariffs on mostly US agricultural goods and the EU hitting back with $37bn of tariffs targeted at iconic US brands.

If implemented, the next round of measures being nosily threatened by President Trump would however represent a huge escalation. These include another US200bn of tariffs on Chinese imports with a further US200bn to potentially follow after that if China again retaliates.The President has also threatened tariffs on all US auto imports, including parts, which could affect up to $360bn of imports. These much larger measures could then see close to a third of the US’s imports hit with tariffs, equating to around 4½% of US’s GDP in 2017.

Massive retaliation from both the EU and China would then surely follow by which stage an all-out global trade war would be undeniable. The EU, which would be the biggest loser from auto tariffs, for example, has threatened to fight back with tariffs of close to$300bn on US exports.

A key concern is the huge gap between the US’s imports from China ($505bn in 2017) and China’s imports from the US (a mere $130bn). The upshot is that China will quickly run out of US exports on which to retaliate if the US escalates further.This imbalance raises the spectre that China will fight back via non-tariff measures such as visa and direct investment restrictions, hurting US corporations’ sizeable direct investments in China.

The nuclearoptionis that China combats further US tariffs via a competitive devaluation; deliberately pushing down its currency, the CNY,against the USD. A global trade war would then risk turning into a global currency war. The CNY is, of course, still tightly managed by the Chinese authorities and backed back by huge FX reserves. And, with the capital account also more tightly screwed down after the devaluation scare of 2015/2016, the Chinese have considerable scope to manipulate the CNY.

Ominously, the CNY has recently weakened notably against the USD; falling over 3% since end-May. The CNY’s weakness can be interpreted as a clear signal to the US that a currency war is an option if Chinese exports are hit with further tariffs.There is no doubt that a currency war could be hugely damaging. With China the world’s biggest consumer of primary commodities, CNY depreciation is, in effect,a global deflationary shock for much of the rest of the world.The USD price of global commodities are pushed down, hurting the export earnings of large commodity exporters and so risking a further ratchet effect to the weakness already seen in many emerging market this year. Financial market volatility would spike across the board and global growth would undoubtedly slow.

But a CNY devaluation is no free lunch for China. Expectations of accelerating currency weakness can easily be unleashed, triggering de-stabilising capital flight that will be hard to keep orderly even with China’s newly tightened capital controls.And CNY weakness would further raise Chinese imported prices on top of the impact of tariffs on US goods, so further adding to the cost of a trade war to Chinese consumers. Both factors – accelerating capital flight and increased inflation pressure –will also add to pressure on Chinese interest rates. With CNY weakness very much a double-edged sword, the Chinese authorities will view it as a last resort, not be used unless a bellicose President trump leaves them with no real alternative.

Four conclusions would seem to stand out. First, the opening shots in a global trade war, whose momentum may be hard to stop, have now been fired. Second,the key to escalation is whether the US follows through on eitherits threatened auto tariffs or further measures against China. Third, increased uncertainty is a building downside risk for the global economy which, excluding the still-booming US, is already showing some signs of losing momentum.Finally, the danger of a trade war morphing into a de-stabilising currency war with China retaliating to further waves of US tariffs with a competitive devaluation is perhaps the greatest risk to global growth.