After a day of no BoEase and a lot of ECBlah, TMM are distracting themselves from a market creep they are not aboard by thinking about the "QE-forever" talk that has never been that far away and about some of its longer term implications.

Now, obviously QE should affect everything denominated in fiat currency and TMM can wax lyrical about how if you define the word ‘help’ in a certain way, QE was the best invention since keyrings. But for brevity’s sake, today TMM will focus on the asset that has the largest impact on consumer behavior – housing. Due to data availability, we will just be look at housing in the US, although arguably the conclusions can be generalised.

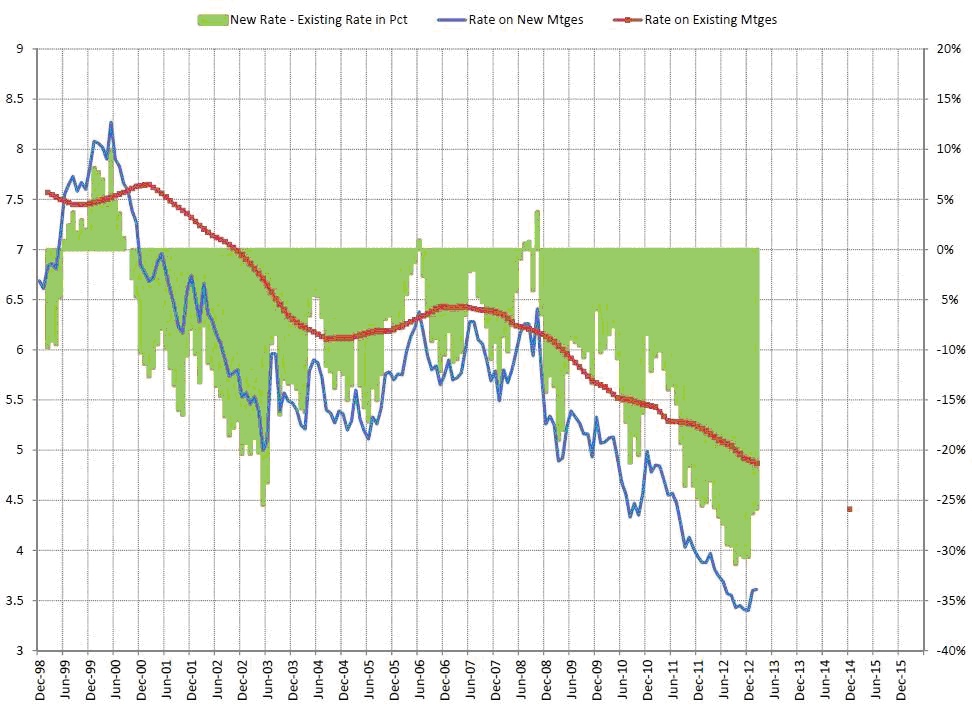

Clearly, by driving down mortgage rates, QE has been enormously helpful for consumer spending. But just how helpful? Well, as of December, the US national average interest rate for existing mortgages was 4.87%, 10% lower than only 2 years ago and a full 17% lower than 2008 levels. If we take the same weightings as the BLS, who apply a 24% weight on primary residence costs in its CPI basket, we could deduce that the 17% drop in effective rates is an implied 4% bump in disposable income, or roughly 1% per year, before wealth effects are taken into account.

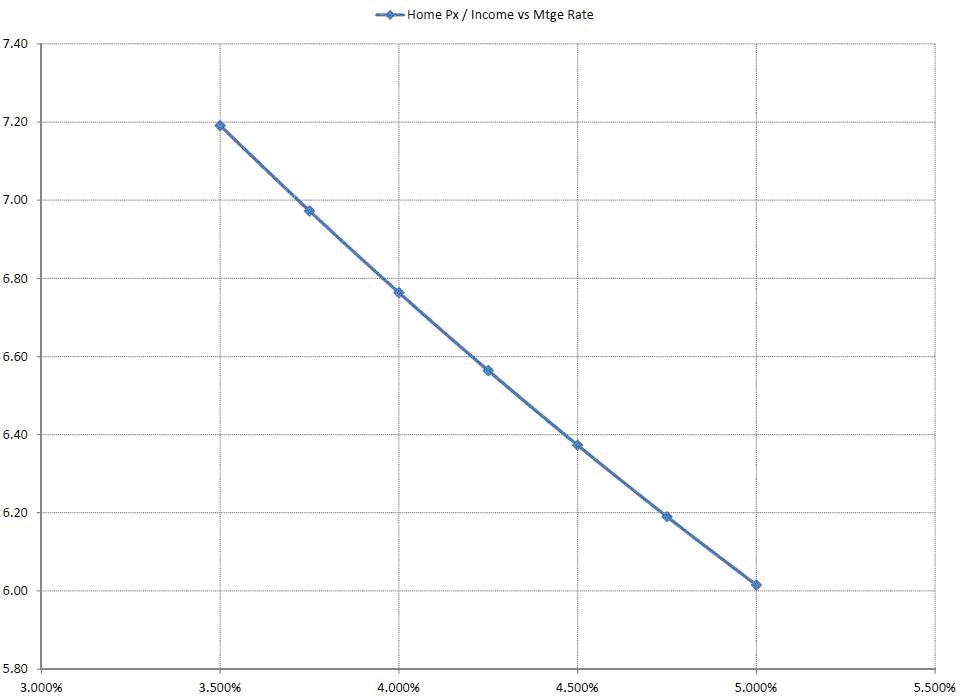

The impact on apparent housing affordability has been no less dramatic. The median US household income as of 2011 was ~$50,000, a level which has been broadly stable for the past 5 years. At the end of 2010, with mortgage rates at 5%, the average US household was able to afford a $301,000 house based on debt to income limitations on conventional mortgages. At the end of 2012, with mortgage rates at 3.5% and with income unchanged, the average family is able to afford a $360,000 house, a 20% increase. In other words, the decrease in mortgage rates has increased the maximum allowable home price to income ratio from 6.0 to 7.2. What’s not to like?

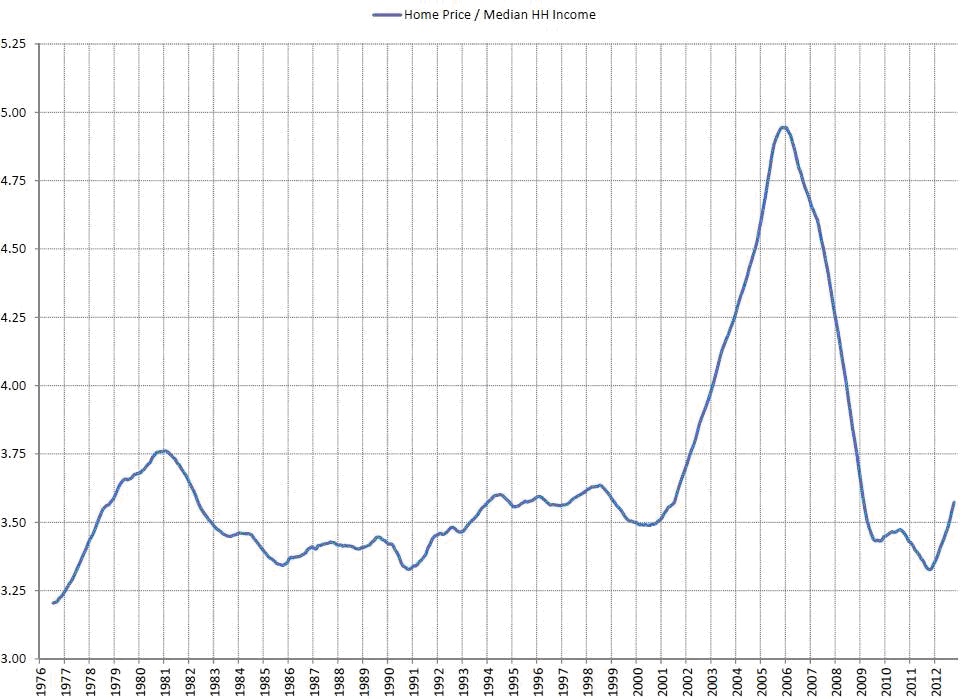

This, of course, is all part of the central bank master plan. By lowering real interest rates, the private sector will take on more debt, spend more, and prosperity can reign. Indeed this seems to be happening and with declining debt payments, US households appear to be re-levering and after a sharp drop, US house prices have started to tick up again relative to incomes:

But wait, there is more good news. Given that rates for new mortgages are still more than 25% below the average for existing mortgages, there is still a substantial easing in store. A continuation of recent trends would result in a further 50bp decline in existing mortgage rates over the next 2 years, (about 10% cheaper).

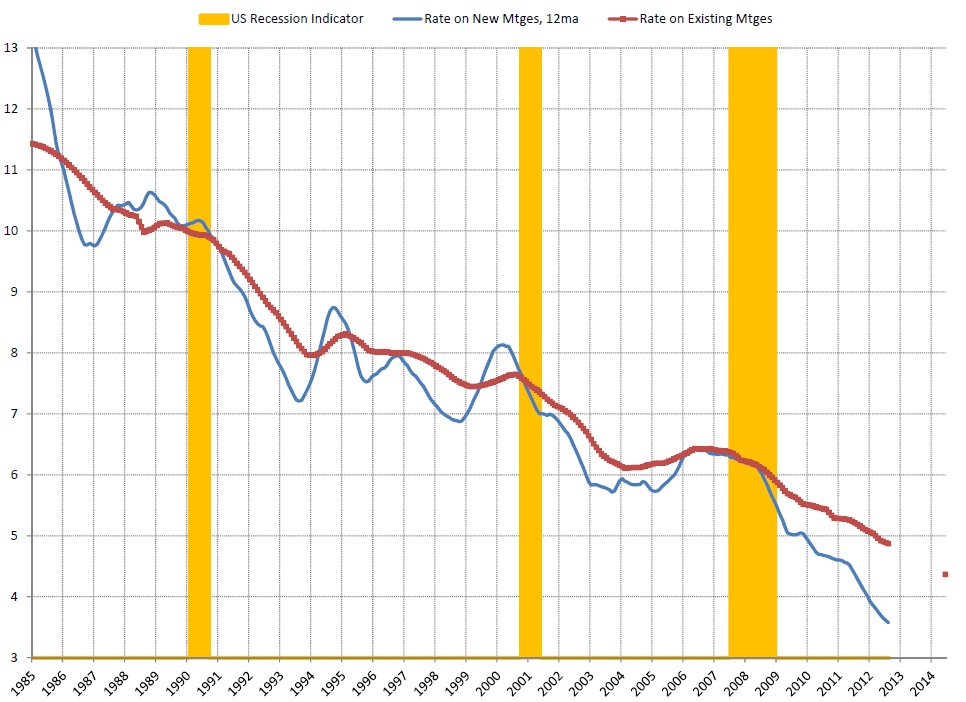

Now you may ask why TMM is concerned with all this good news (not that we don't like good news). The answer is embedded in the chart above. Note that the US has never survived an instance in the last 14 years where new mortgage rates exceed existing mortgage rates without the economy tipping into a recession. And that makes sense. Without increases in real income, mortgage rates which are no longer supportive to house prices ultimately result in declining expenditures. In other words, and this is the worrying implication, without income growth there is an interest rate at which the US will tip into a recession. And that rate is declining, even as the private sector re-leverages. In 2 year’s time, that rate will probably be ~4.5% for fixed rate mortgages. If mortgage to treasury spreads stay constant at ~150bps, that would imply a 3% recessionary ceiling for 10y treasury yields.

However, going further back in history we can see that there is one clear exception to this crossover rule. The 1994 bond collapse, where the swift and severe bond market fall had to be swiftly countered by Fed policy response to successfully contain economic fallout.

However today's proximity to the zero bound in both Fed rates and mortgage rates themselves sees there being no room to manoeuvre with either input other than with more QE. QE has been described by various prognosticators as a drug. On this basis TMM find it hard to disagree.

Now here is another little twist we have spotted. In addition to the fact that declining interest rates encourage leverage, they also act as a price for intergenerational wealth transfer. Huh? Well, new home buyers tend to be predominantly young families, while sellers tend to be retirees. As lower interest rates increase the present value of housing prices, new buyers increase leverage to purchase homes, and they take on a larger debts to do so.

Lower interest rates have helped delay the need to restructure social security and medicare, thereby allowing their funded status to worsen. As those programs are essentially inter-generational transfer vehicles, their worsening financials have been described as akin to the elderly stealing from the young. TMM would like to point out that artificially low mortgage rates do the same thing.

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Polski

- Português (Portugal)

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

On Housing: Rate Traps And Mortgage Twists

Published 03/08/2013, 01:44 AM

Updated 07/09/2023, 06:31 AM

On Housing: Rate Traps And Mortgage Twists

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.