During my daily radio broadcast Tuesday, I received a rather "panicked" call regarding the "dramatic plunge" in his bond funds due to the recent jump in interest rates. Of course, he is not alone. Over the last few weeks the media has done its normal headline-grabbing spin by dragging out every bond "bear" they can find to discuss why this time, unlike like the last 30 times, is definitely the end of the "great bond bull market."

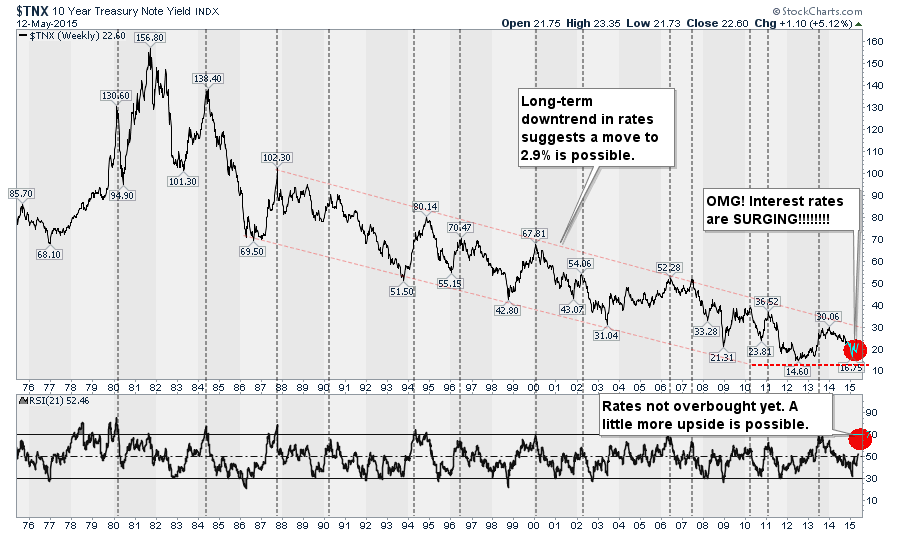

First, let's put the recent "short covering squeeze" in the bond market into perspective. The chart below is a 40-year history of the U.S. 10-Year interest rate. The dashed red lines denote the long-term downtrend in interest rates.

The recent SURGE in interest rates is hardly noticeable when put into a long-term perspective. After rates dropped to their second lowest level in history of 1.68%, only exceeded by the "great debt ceiling default crisis of 2012" level of 1.46%, the recent bounce to 2.26% was expected.

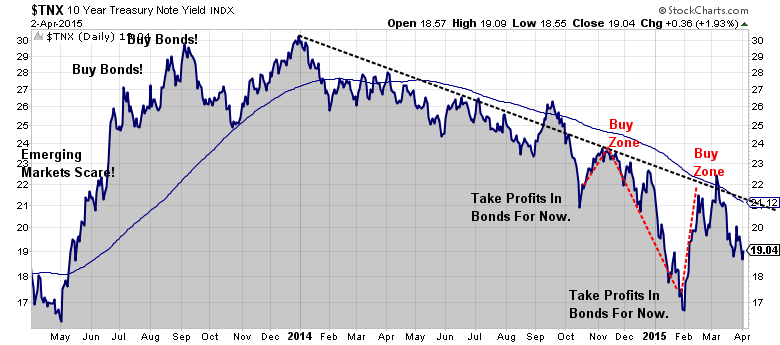

As I addressed in my weekly newsletter, I recommended SELLING bonds at the beginning of April stating:

"I recommended buying bonds several weeks ago when rates spiked up on rumors that the Fed might actually raise rates. (Hold on a second, I can't see through the tears of my laughter)

Okay, I'm back. It is advisable to again take profits on a decline in rates to 1.8% or less. Bonds are going to continue to be a great trading vehicle for the next several years as the realization of a stagnationary economic environment settles in."

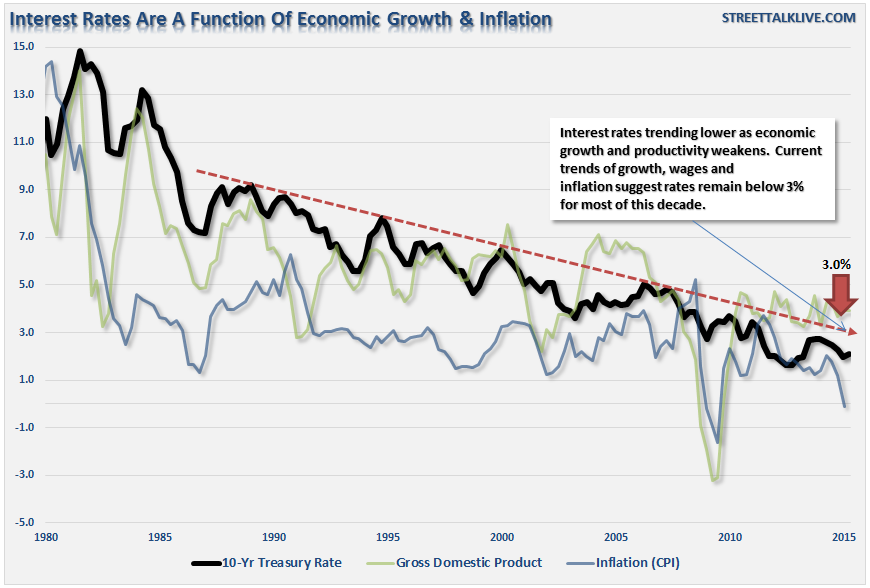

Secondly, the recent rise is well contained within the long-term downtrend that has been in place since the 80's. Since interest rates are ultimately a function of inflation and economic growth, there is little data that currently suggests that rates will begin to rise substantially any time soon. To wit:

"With economic growth running at exceptionally low rates, along with inflationary pressures and monetary velocity, interest rates will remain range-bound at low levels for quite some time. This is simply because interest rates are a reflection of the demand for credit over time, in weak economic environment higher rates cannot be sustained. The chart below shows and confirms the above."

"Therefore, the recent uptick, as recommended in last weekend’s newsletter, is now a buying opportunity for bonds. Use any push from current levels to as high as 2.7% to increase exposure in individual bonds that will be held until maturity and bond funds/ETF’s for the next trading opportunity"

The last sentence is crucial. For investors, there is a HUGE difference between bond funds/bond ETF's and individual bonds.

Bond funds/ETF's are a "BET" on the direction of interest rates. They do not mature and have NO return of principal function. Therefore, it is crtiical that investors employ some measure of risk management in portfolios with interest rate movements just as they do with equity markets. This is particularly important with interest rates at current levels. Over the next decade, or longer, interest rates will likely be range bound at current levels as economic growth and inflationary pressures remain nascent.

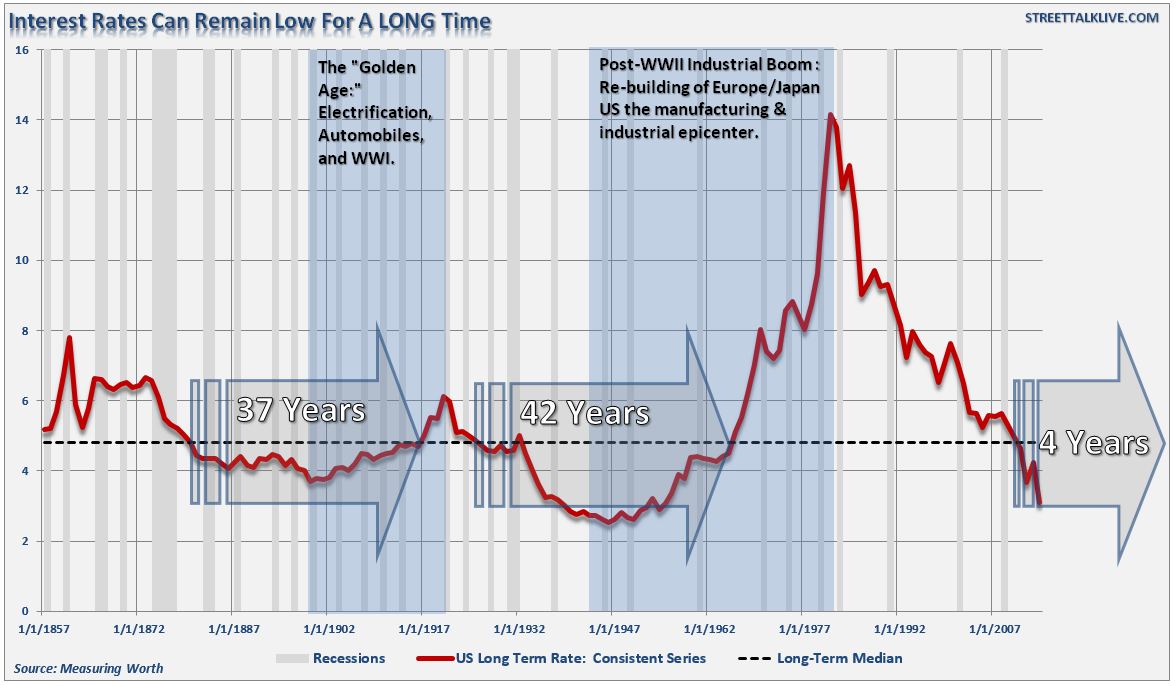

History shows this is not the first time that such an environment has existed in the U.S. As I wrote previously:

"The chart below is a history of long-term interest rates going back to 1857. The dashed black line is the median interest rate during the entire period."

"Interest rates are a function of strong, organic, economic growth that leads to a rising demand for capital over time. There have been two previous periods in history that have had the necessary ingredients to support rising interest rates. The first was during the turn of the previous century as the country became more accessible via railroads and automobiles; production ramped up for World War I and America began the shift from an agricultural to an industrial economy.

The second period occurred post-World War II as America became the 'last man standing' as France, England, Russia, Germany, Poland, Japan and others were left devastated.

Currently, the U.S. is no longer the manufacturing powerhouse it once was and globalization has sent jobs to the cheapest sources of labor. Technological advances continue to reduce the need for human labor and suppress wages as productivity increases. Today, the number of workers between the ages of 16 and 54 is at the lowest level relative to that age group since 1976. As discussed recently, this is a structural problem that continues to drag on economic growth as nearly 1/4th of the American population is now dependent on some form of governmental assistance."

As shown, periods of low interest rates in the US are not unique and have lasted about 40-years on average. At just four years, it is quite likely that we will be harnessed in a lower trading range for quite some time. This will force investors to become more adept at "trading" interest rates after being lulled into complacency after 30-years of a steady decline.

The problem with most of the forecasts for the end of the bond bubble is the assumption that we are only talking about the isolated case of a shifting of asset classes between stocks and bonds.

However, the issue of rising borrowing costs spreads through the entire financial ecosystem like a virus. The rise and fall of stock prices have very little to do with the average American and their participation in the domestic economy. Interest rates, however, are an entirely different matter.

While there is not much downside left for interest rates to fall in the current environment, there is also not a tremendous amount of room for increases. Since interest rates affects "payments," increases in rates quickly have negative impacts on consumption, housing, and investment.

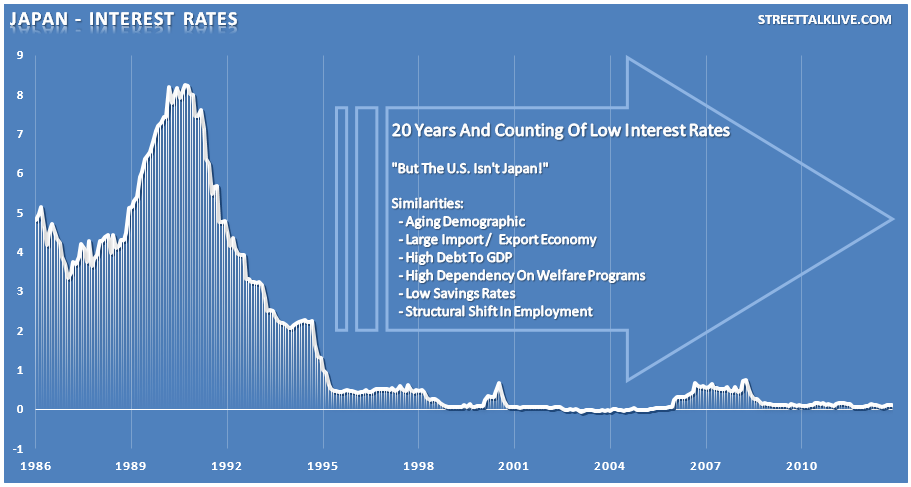

This idea suggests is that there is one other possibility that the majority of analysts and economists ignore which I call the "Japan Syndrome."

Japan is has been fighting many of the same issues for the past two decades. The "Japan Syndrome" suggests that while interest rates are near lows it is more likely a reflection of the real levels of economic growth, inflation, and wages. If that is true, then rates are most likely "fairly valued" which implies that the U.S. could remain trapped within the current trading range for years as the economy continues to "muddle" along.

So, can we just put the recent bump in interest rates into some perspective? Will the "bond bull" market eventually come to an end? Yes, eventually. However, the catalysts needed to create the type of economic growth required to drive interest rates substantially higher, as we saw previous to the 1960-70's, are simply not available today. This will likely be the case for many years to come as the Fed, and the administration, come to the inevitable conclusion that we are now caught within a "liquidity trap" along with the bulk of developed countries.