Denmark: sheltered for now, headwinds ahead

Sweden: danger signs accumulating

Norway: economy approaching peak

Finland: winter is coming

At a glance

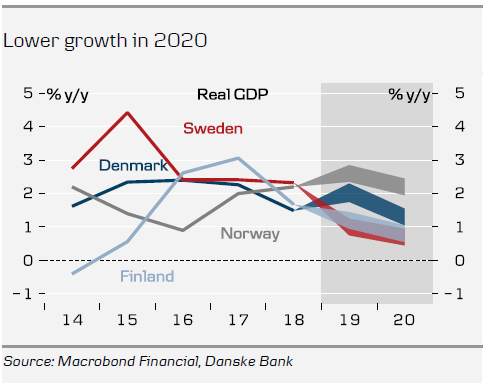

A darkening outlook

Since our last Nordic Outlook, the global economic situation has taken a turn for the worse. Manufacturing seems to be in a global recession, with Germany especially hard hit. The trade war between China and the US no longer looks likely to be resolved soon, and that is affecting global investments. The Nordic countries have held up remarkably well, but weaknesses are beginning to show, and it looks like the best part of the recovery is behind us or soon will be, even in Norway which remains supported by strong growth in oil investment.

That does not mean that we are facing an economic crisis in the Nordic countries. We still forecast growth not too far from the economies’ potential, with Sweden as the most troubling case. We have had a period of strong growth and rising employment across the Nordics and it is natural for that to come to an end. But the risk is that a natural slowdown turns into something worse. That risk is not equal across the Nordic countries. A crisis looks highly unlikely in Norway, whereas Sweden is at risk not just from the global slowdown, but also from a sharp decline in domestic spending growth, especially within housing investment.

If it becomes necessary, the Nordics are well placed to react to signs of crisis. Again Norway is ahead, with both ample room to loosen fiscal policy and as one of the few countries in Europe that has the option of cutting interest rates substantially – although in our main scenario, it looks more likely that rates will be hiked. Also Sweden and Denmark have very sound public finances and can easily afford to mitigate a crisis. According to the thinking in the European Central Bank, they should probably ease fiscal policy even in the absence of a crisis to take the pressure off monetary policy, but that is not on the agenda of either government. Finland’s position is a little more difficult, as public finances are less strong and face strong structural headwinds in the future.

Brexit is a further risk

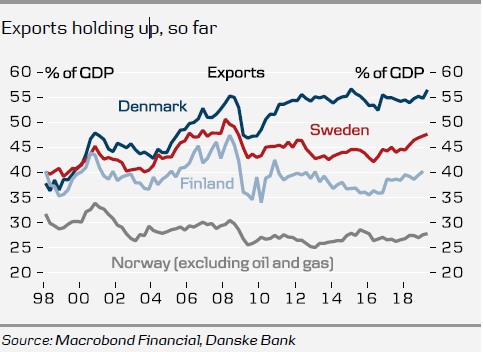

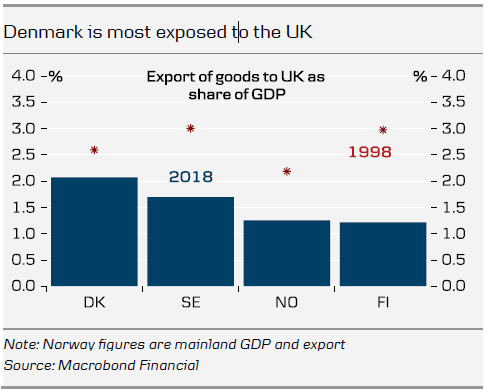

Trade war tensions are mostly between China and the US, with limited direct effect on the Nordics, although sectors such as Danish shipping are clearly affected. If the US starts to target Europe, Nordic producers would also be affected, for instance as part of the European car industry. A disorderly Brexit would create problems closer to home and affect many Nordic companies directly. If it triggers a short-term recession, this would be felt in the rest of Europe. In terms of direct effects, Nordic exporters would be likely to face tariffs on some on their UK exports and all Nordic countries have a surplus against the UK in goods (but a deficit in services). Norway has the most exports, but 80% of this is oil and gas, which face only 2.5% tariffs under rules and on which the UK government intends to impose no tariffs in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

Denmark’s substantial food exports would have to deal with more significant tariffs and would also face increased competition from non-EU producers.

However, the total value of agricultural exports to the UK is only 0.5% of Danish GDP. The UK is not as important as it once was to the Nordics and we do not expect a major economic impact beyond the immediate effect.

Denmark

Sheltered for now, headwinds ahead

Few signs of weakness for now

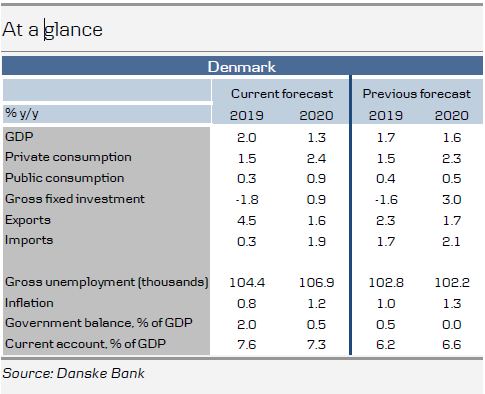

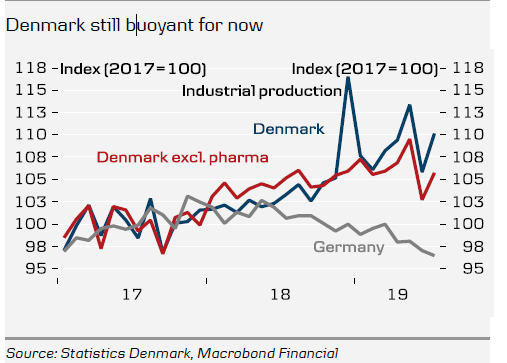

The Danish economy continues to perform surprisingly well compared to its neighbours. GDP growth was solid in the first half of 2019, whereas the German economy stalled and the real rate of growth in Sweden was very modest. Even more remarkable is the fact that exports have been a key driver behind Denmark’s economic growth despite global trade suffering from a worldwide slowdown in manufacturing. Part of the explanation at least is the strong Danish pharmaceutical and wind turbine industries, which are seeing exports grow and are not as dependent on the global business cycle as, for example, the rest of the machinery industry. Based on growth rates in H1, we have revised our growth expectations for 2019 higher, even though we have become more pessimistic on growth in the rest of the world. Looking a little further ahead, however, we expect that Denmark will, as usual, follow the general global trend. We have therefore revised down our expectations for growth in 2020, when we presume the global slowdown will affect both exports and business investment in Denmark.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has strongly encouraged countries in a position to ease fiscal policy to do so in order to lift growth and inflation in Europe, which the ECB itself has difficulty doing through, for example, further interest rate cuts of questionable effect. Denmark has some of the healthiest government finances in Europe and so is in a position to ease. However, the Danish economy has no real need for fiscal easing – unemployment, for example, is low, even though we expect it to rise slightly. Should Danish politicians decide to heed the ECB’s call, it would be at odds with the usual Danish approach and also the spirit of the Danish budget. Nevertheless, the risk of such actions triggering overheating is no higher than in other European countries, while the risk of a crisis in confidence and, for example, markedly higher interest rates in Denmark is very small.

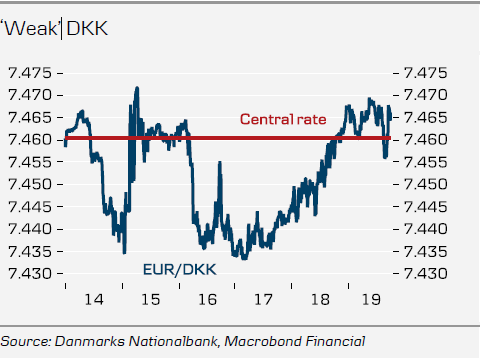

Interest rates set to remain low

Danmarks Nationalbank lowered its certificates of deposit rate from -0.65% to -0.75% in September. This came on the heels of a matching rate cut by the ECB, yet it triggered the greatest one-day weakening of the Danish krone (DKK) since 2015. This was due to the ECB’s rate cut being in reality less, as the bank also introduced a new system, so-called tiering, that exempts some central bank deposits from negative interest rates. The DKK is now trading weak relative to the central parity rate, but Danmarks Nationalbank has ample opportunity to intervene in the FX market if necessary to hinder further weakening, and so we do not expect any imminent unilateral rate hike. Long yields have fallen in Denmark – just as in other parts of Europe – as expectations on growth and inflation have faded and the ECB has restarted its bond buyback programme.

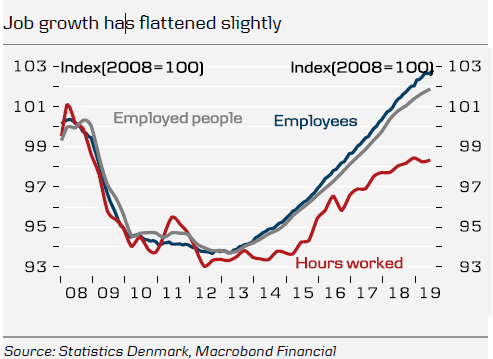

Labour market in balance

Several indicators suggest the labour market has slowed this year despite solid GDP growth. Labour shortages have eased, for example. However, this could be connected to much of the country’s economic growth occurring in sectors that have high productivity levels and much of their production abroad. That being said, the labour market slowdown has been slight and unemployment has barely risen – despite the labour force growing quite strongly, in part due to the increasing retirement age. The labour force will continue to grow in the coming years, and given more subdued expectations for growth, we now expect to see a small increase in unemployment – though there is a great deal of uncertainty about this due, for example, to foreign labour, which could potentially depart as the slowdown continues.

Private sector wage growth is running at just under 2.5% annually, which is low, but in real terms on a par with the historical average due to the low level of inflation. This reflects a labour market more or less in balance and also fits well with what we see among Denmark’s trading partners. Given the prospect of slightly higher unemployment, real wage growth could fall modestly, but as inflation is also expected to increase slightly, we are looking for essentially stable growth in nominal wages. The average wage (which is what is shown in our forecast) is rising somewhat slower, which may reflect relatively more people being hired in lower wage jobs.

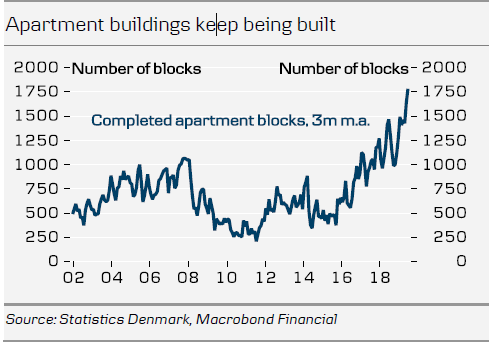

Investments normalised

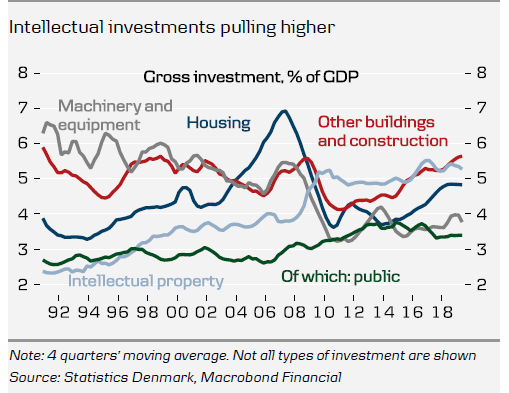

The upswing has in part been driven by rising corporate and housing investments after the financial crisis. Overall, investments are now back at historical norms, and we expect a lower contribution to growth from this front going forward, especially given the prevailing general slowdown. Investments in intellectual capital, such as patents, have been particularly high, especially in the pharmaceutical area. In contrast, machinery investments have been low. One could speculate as to why the low level of interest rates has not stoked higher levels of investment both in Denmark and in other parts of the world.

Explanations may include the slowdown in productivity growth, greater general uncertainty and lower risk appetite.

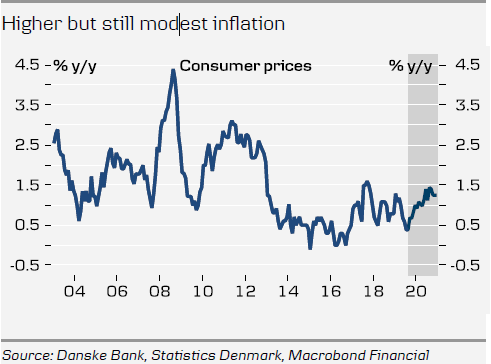

Higher – but still low – inflation ahead

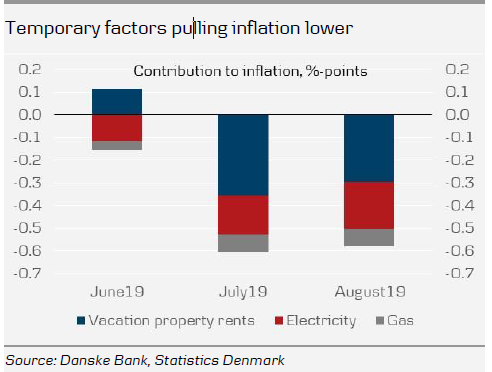

Inflation in Denmark is low and has been for quite some time. Since 2018, much of the reason has been modest rent increases. Inflation fell to 0.4% over the summer, due to a number of temporary factors. For example, the weighting on vacation property rents in the consumer price index has fallen markedly this year, which pulled inflation sharply lower during the summer holiday season.

Electricity and gas prices have also fallen heavily, with the fall in electricity prices mostly due to the PSO levy being set to zero in Q3. However, the PSO levy will not be phased out until 2022 and has been hiked considerably higher again for Q4. Both factors will contribute to pulling inflation up towards 1% again around the end of the year.

We also expect inflation to rise a little further next year. Tobacco duties will probably be raised on 1 January and if, as seems likely, the government’s solution is to hike the price of a packet of cigarettes by DKK10, with the price initially rising by DKK5, we estimate this will contribute 0.19 percentage points to inflation in 2020. That being said, the parties that wish for a greater increase are in the majority, so the price rise could be higher (see Cigarette prices pose significant upside risk to Danish CPI inflation, 29 May, for more details).

Wage increases in Denmark remain modest, and without an increase in labour market pressures it is difficult to see what might create significantly greater price pressures. We estimate inflation will come in at 0.8% this year and 1.2% in 2020.

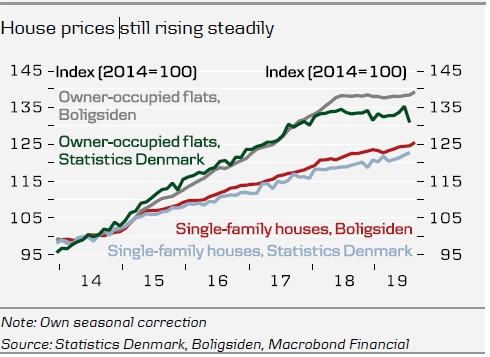

Falling interest rates lift house prices more than apartment prices

We expect house prices to rise by around 2.5% nationally this year and next, supported in part by low interest rates that have fallen further in 2019. That we do not expect higher price rises on housing is due, among other things, to the steam going out of the business cycle and the past year’s lacklustre growth in apartment prices, which means lower capital gains from home sales and thus less money for housing purchases.

The housing market is experiencing additional uplift at the moment from the fall in interest rates in recent months. We expect this to have a somewhat greater impact on house prices than on apartment prices – especially in the more expensive areas. Here, it is not necessarily the financing costs that will determine how much can be borrowed, but rather other factors, such as income levels and payment capabilities. This has to be seen against the tightening of credit terms in recent years, which as well as making the apartment market in Copenhagen less interest-rate sensitive, is also much of the reason for the slowdown that has been ongoing since last spring.

To read the entire report Please click on the pdf File Below..