An interesting report by Reuters explores the vagaries of supply from Indonesia and the Philippines, the world’s two largest nickel producers — and, unfortunately for the nickel price, it would seem two of the least reliable suppliers.

Source: Reuters

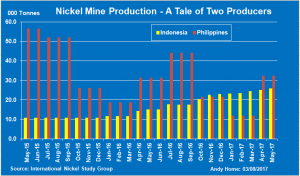

By far and away the most volatile supplier has been the Philippines.

Former Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources Regina Lopez’s mining crusade and resulting export ban last year had a cataclysmic effect on output from which the country has not recovered, despite her replacement in May by Roy Cimatu, Reuters reports.

The latest assessment by the International Nickel Study Group (INSG) notes the country’s nickel production fell by 15% to 101,000 metric tons in the first five months of this year. Shipments of nickel ore to China have also been flowing at a reduced pace. Chinese imports from the Philippines slid by 6% over the first half of the year, according to Reuters.

Indonesia’s supply constraint, on the other hand, was driven by a policy to achieve greater value add in-country, started by a 2014 export ban on unprocessed ore which has only recently seen a partial rollback, as progress has been made in setting up nickel pig iron plants in the country. There are now multiple nickel “smelters” producing nickel pig iron or equivalent intermediate product in Indonesia, Reuters reports, quoting INSG estimates that mined production has surged 89% to 122,000 tons in the January-May period.

Meanwhile, the market has been responding to these political proclamations and about-turns with dramatic changes in short and long positions.

Reuters quotes LME Commitment of Traders figures to support price movements and investor position taking. The 18% nickel price rally over the last month to $10,445, a five-month high, followed investors flocking back to the market driving net long positions to 32,363 lots, compared with a net short of 887 lots on May 15. The return to the market seems to have been on the back of the nickel price’s fall to a year’s low of $8,680 and the widespread belief — supported by the closure of half of Indonesia’s processing plants — that refining becomes uneconomic below a nickel price of $9,000 per metric ton.

If $9,000 is the price floor based on current technology, what is the upside, stainless consumers will be asking?

In part, that depends on the potential for constraints to supply.

Demand remains solid. Reuters states Chinese imports of Indonesian “ferronickel” (nickel pig iron) broke through the 100,000-ton barrier in May and stayed there in June, while cumulative imports in those two months were 270,000 tons (bulk weight), exceeding total imports in 2015.

Demand, therefore, remains solid, but so too does supply. Netted between them, the two countries produced 223,000 tons of nickel in the first half of this year, up from 184,000 tons in the same period of 2016, according to the INSG. China’s imports of nickel raw materials, ore and concentrates, were also up in the first half of this year by 4% (not counting the separate flow of Indonesian ferronickel).

Providing Cimatu continues with his conciliatory approach to miners, the market is likely to conclude exports are going to continue. The market has a floor at $9,000 per ton, but according to Reuters it could also be capped by rising supply as both countries ease restrictions and supply remains adequate.