The message coming from central bankers is clear: The beatings will continue until morale improves.

If the global equity markets don’t perform well, negative interest rate coercion will be meted out.

Last week, Sweden’s central bank, the Riksbank, cut its key interest rate from -0.35% to -0.5%. Two weeks ago, the Bank of Japan “unexpectedly” joined the negative interest rate policy (NIRP) movement.

Thanks mostly to NIRP, there now exists $7 trillion worth of negative-yielding government bonds around the world.

Central bankers seem to think that adding to this heaping pile of wealth-destroying securities will solve our problems.

In an interview with MarketWatch in December, former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke said, “I think negative rates are something the Fed will and probably should consider if the situation arises.”

Last week, Fed Chair Janet Yellen testified before Congress and noted that the Fed is “taking a look at” negative rates.

With economic growth flagging and inflation expectations collapsing, it seems as though the “situation is arising” far faster than the Fed anticipated.

According to the federal funds futures market, the prospect of additional U.S. rate hikes in 2016 is evaporating. Meanwhile, the implied probability of a rate cut has become non-zero.

Here’s Where It Gets Scary

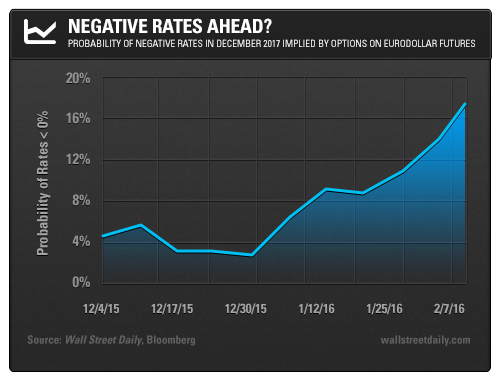

The following chart shows the rising probability of negative rates in the United States.

Here, the probability of negative rates is derived from options on 90-day Eurodollar futures.

Eurodollars are U.S. dollar bank deposits located outside the United States, and, hence, not subject to U.S. banking regulations. Eurodollar rates closely follow the fed funds rate.

All of this means that a negative policy rate is starting to become a very real possibility.

Now, let’s not lose sight of the true purpose of unconventional monetary policy. The world has too much debt relative to economic output. We’re at the end of an up wave in the multi-decade debt supercycle.

Without stimulus, the debt levels would normalize in a painful, but ultimately beneficial, process.

However, central bankers don’t want to allow this necessary credit contraction. Thus, they’re forced to implement increasingly extreme policy measures to try to foster continued credit and debt growth.

Expect more desperation from central bankers, even if they’re just postponing the painful readjustment.

Safe (and high-yield) investing,