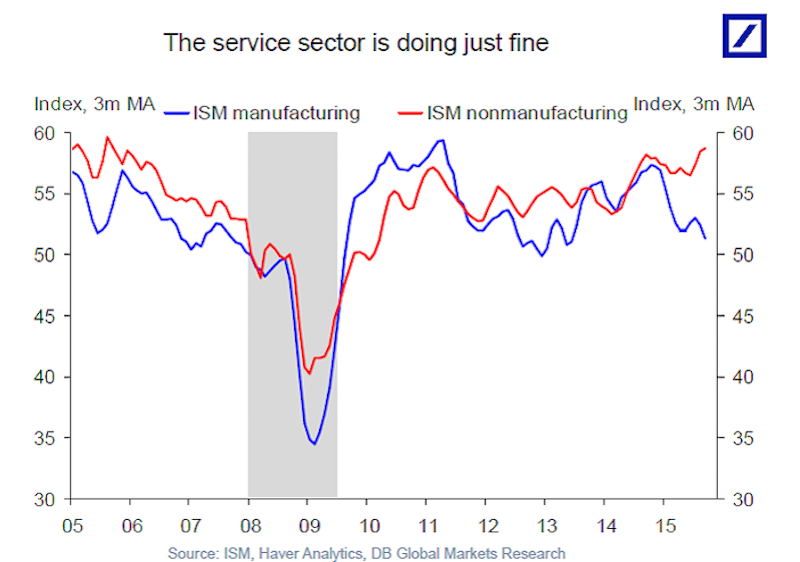

There has been a bit of chatter going on lately about the divergence of the services sector from the manufacturing sector of the economy. This note from David Rosenberg took note of that divergence.

"We are seeing questions come up as to whether a manufacturing recession means that the broader economy is destined to follow suit?"

His answer is that such an outcome is likely not the case. His belief is that manufacturing is no longer a good bellwether for the overall economy. Currently, manufacturing makes up just 12% of total economic output, down from about 30% in the 1950s.

However, is this really the case?

There are a couple of problems with discounting the importance of manufacturing from the economic debate.

First, is the impact on jobs. As Sam Ro wrote this morning:

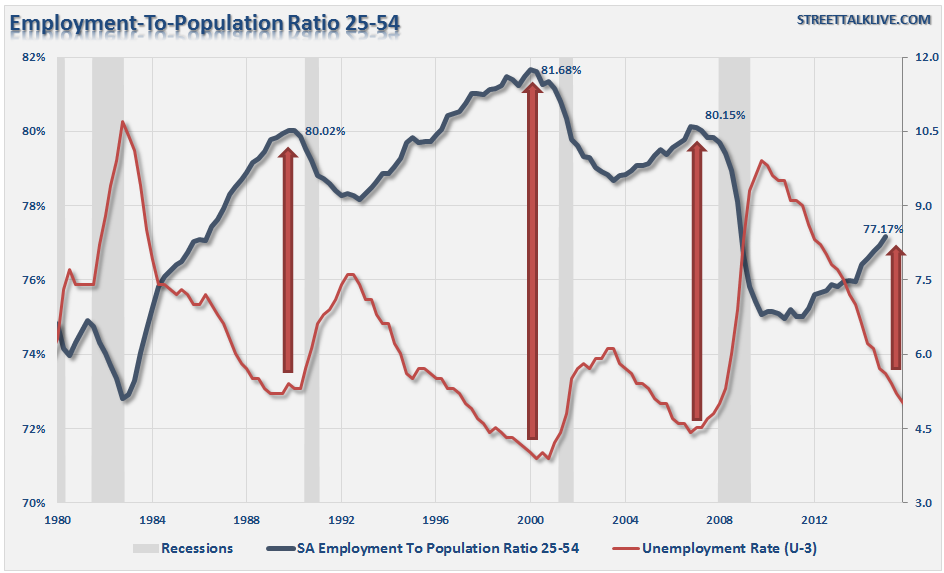

"With the unemployment rate having tumbled to a 7-year low of 5.0%, the employment factor is not the concern."

While the unemployment rate, as measured by the BLS, has fallen to a 7-year low, there is vast difference between now and when it has previously achieved such levels. In order to sidestep all of the arguments about retiring "baby boomers" and "students," let's focus on the 25-54 age groups which are in their prime working years. As shown in the chart below, when the unemployment rate had previously achieved "full employment" levels, more than 80% of the prime working age group was employed. Today, that number is 77%.

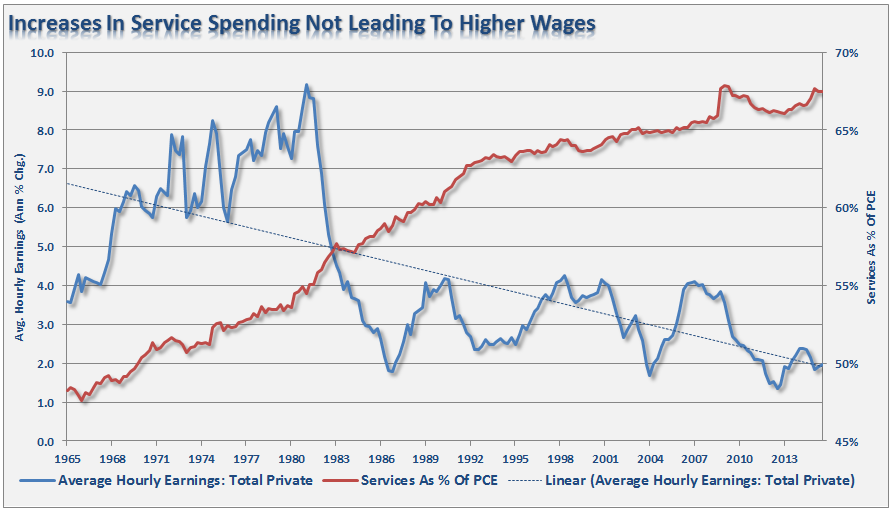

The problem is not only the current employment level remaining well below levels normally associated with previous "full employment," but wages also remain suppressed. While the recent uptick in wages was certainly welcome by those receiving it, the problem is that the long-term trend of wages remains in a downward slide.

The problem, of course, is that service related jobs are primarily lower-skilled and therefore lower wage paying jobs than those found in manufacturing. Secondly, service-related jobs have a very low multiplier effect throughout the economy as opposed to manufacturing jobs which leads to lower rates of employment growth, hence the stubbornly slow rate of job growth witnessed since the end of the last recession.

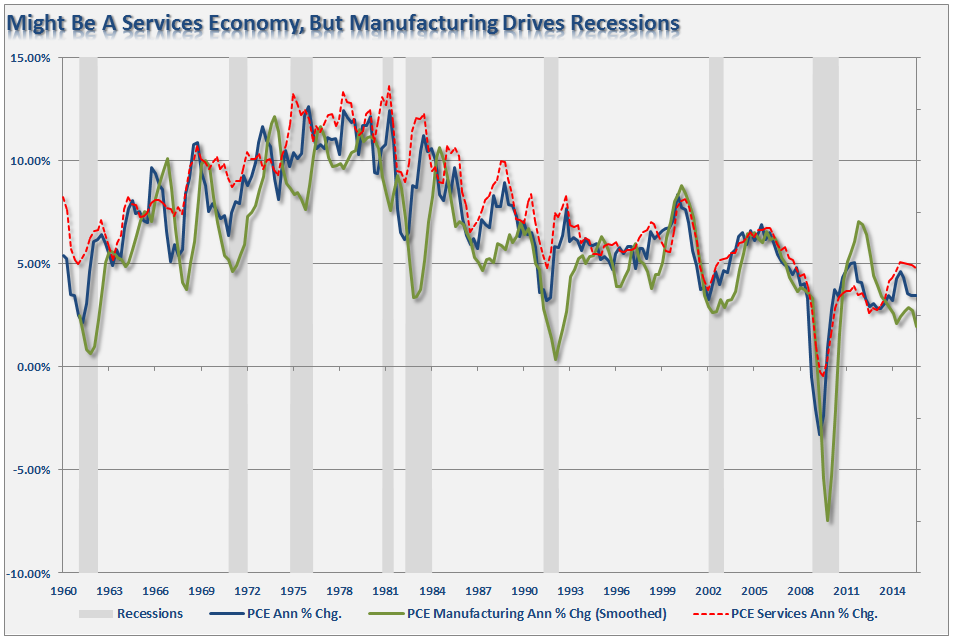

Since personal consumption expenditures drives roughly 70% of economic growth, a look at where consumers are spending money gives a bit of different picture as opposed to the breakdown of the ISM surveys above. The chart below shows the annual rate of change in total personal consumption expenditures, manufacturing and services.

As you will note, there are many times historically when service related spending has diverged from manufacturing. However, such divergences have tended not to last long and ultimately it has been spending on manufactured goods that have ultimately dictated economic cycles.

Again, this makes sense when you think about the effect of each dollar spent by consumers. As noted, a dollar spent on services tends to have a relatively small multiplier effect within the economy as opposed to the impact created by spending on manufactured goods and services.

As David correctly noted, the economy has changed from a manufacturing-based economy to a service related one. However, as service-related spending continues to absorb more of every dollar spent by households, it continues to weigh on wage growth.

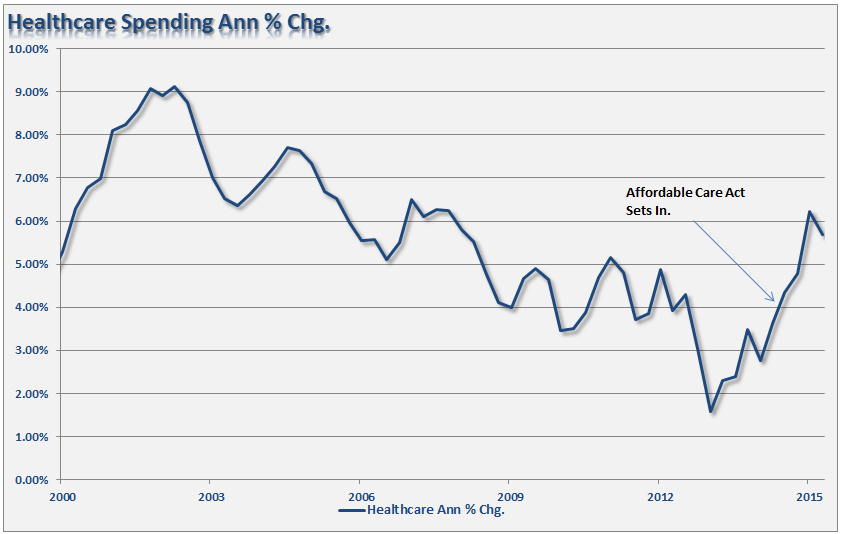

This is particularly the case with more service spending heading toward surging healthcare costs. The impact of the Affordable Care Act is now taking root. Unfortunately, for many, that impact is not a positive one as surging premiums absorb more of the discretionary budget of households.

While it is hoped that the economy can continue to expand on the back of the "service" sector alone, history suggests that "manufacturing" continues to play a much more important dynamic that it is given credit for.

The decline in imports, surging inventories and weak durable goods all suggest the economy is weaker than headlines, or the financial markets, currently suggest.

For now, however, that detachment can last a while longer as global Central Banks continue to suppress interest rates and flood the financial system with liquidity. With levels of subprime loans for autos and houses, debt issuance and share buybacks once again sharply on the rise, the "party" rages on. However, it is worth remembering what happened when the bartender previously shouted "last call."