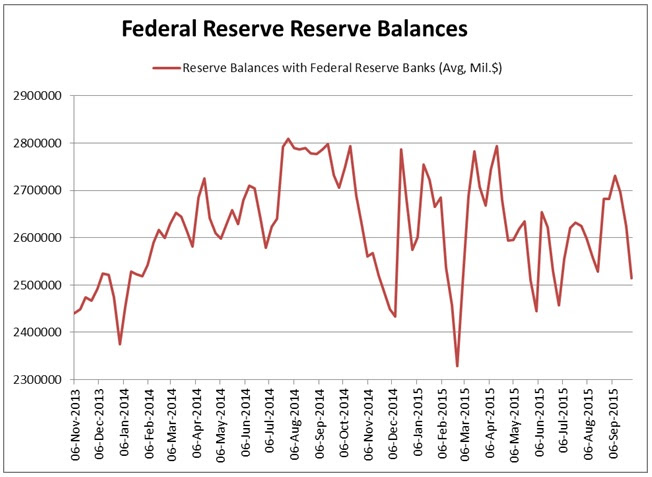

A friend and fellow member of the National Business Economic Issues Council points out what appears to be a puzzle in recent Federal Reserve balance sheet data, and that is a drop in reserves. Reserve balances have fluctuated by as much as $300 billion. Where did they go? Is this an unusual event? The chart below shows that there was a recent drop in bank reserves, but similar drops also occurred beginning in the fall of 2014 and into this year.

The short answer is that the reserves didn’t go anywhere but were simply transformed into reverse repo liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet temporarily. This is part of the System Open Market Desk’s experiment using reverse repos as a new tool that it envisions employing as the FOMC begins to restore policy to a more normal stance.

We have written about reverse repos in three past commentaries: “Are Reverse Repos the Answer to the Fed’s Exit Problem?” (December 16, 2013), “More on the Fed and Reverse Repos” (December 18, 2013), and “Reverse Repos” (June 2, 2014).

As we approach the time when the Fed is likely to raise rates, either in December of this year or sometime next year, it is worthwhile reviewing how the reverse repo transaction works and how it affects the Fed’s and participating institutions’ balance sheets. Our discussion will simplify the transaction by skipping over certain technical details, namely the fact that the transactions take place through the tri-party repo market, in which an intermediary actually stands between the Fed and its counterparty to take possession of the securities involved and is involved in settlement.

Exactly what do we mean by a reverse repo in its simplest form? Here the Fed uses confusing terminology. What the Fed is doing is temporarily selling securities from its portfolio under a contract to buy them back the next day or sometime in the future. Normally, such a transaction would be called a repurchase agreement, or repo, and the contract from the counterparty’s perspective would be termed a reverse repo. Instead of calling this transaction a repurchase agreement, the Open Market Desk chooses to name the transaction from the counterparty’s perspective, hence the term reverse repo.

The Desk has used such overnight transactions as part of its normal conduct of daily monetary policy transactions for many years. Bids were taken, and the rate on the transaction was the difference between the agreed-upon sales price and the buyback price, which was lower. What has changed, and what is reflected in the above chart, is that in September 2013 the FOMC authorized a limited experiment with the offering of a fixed-rate overnight reverse repo transaction, initially limiting to $500 million the amount sold to any one counterparty. It also expanded the number of counterparties beyond just primary dealers to include, for example, qualified money market funds. Then in October 2014 the FOMC authorized the Desk to engage in a series of term reverse repo transactions with an aggregate limit of $300 billion. These programs explain the fluctuation in bank reserves shown in the chart above. (The growth in reserves shown in the chart was related to the Fed’s QE programs.)

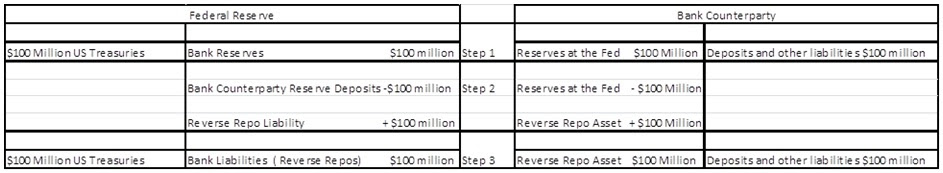

In simple terms, what happens to bank reserves when the reverse repo transactions occur? The T-accounts below show the transactions, assuming a $100 million transaction with a member bank counterparty. (All transactions flow through member bank accounts with the Fed, even if the actually counterparty isn’t a bank.) In the accounting for the transaction, even though there is a temporary sale of Treasuries from the Fed’s portfolio, the convention is to keep those Treasuries as assets on the Fed’s balance sheet; thus only the liability side of the ledger is affected, and only the asset side of the bank counterparty’s balance sheet is affected.

Step 1 shows the initial Fed and counterparty balance sheet assets and liabilities. Step 2 shows the creation of the reverse repo and corresponding reduction in bank reserves. Step 3 shows the resulting change in asset and liability compositions.

There are three important points from this transaction. First, the transaction does not affect the size of either the Fed’s balance sheet or that of the counterparty. The transaction only changes the composition of the Fed’s liabilities and the counterparty’s assets. Second, what does change is that bank reserves are converted into reverse repos, which cannot be used to meet required reserves or to make loans. Thus, the transaction sterilizes a portion of bank reserves held at the Fed. Finally, since the size of the Fed’s balance sheet hasn’t changed, the reserves haven’t really disappeared; they have simply been transformed.

The Fed’s balance sheet, and hence bank reserve balances, can shrink only if the Fed sells assets or if assets mature and are not replaced. (We are ignoring here a reduction in outstanding currency.)The maturing process will also shrink bank reserves, but the process is too complex to explain in this commentary. The importance of the reverse repo transaction is that it would enable the Fed to gradually shrink its balance sheet without engaging in asset sales, while at the same time creating an interest rate mechanism as a policy tool while also sterilizing bank reserves. This means that Fed interest rate policy can be independent of the size of its balance sheet.

Bob Eisenbeis, Vice Chairman & Chief Monetary Economist.