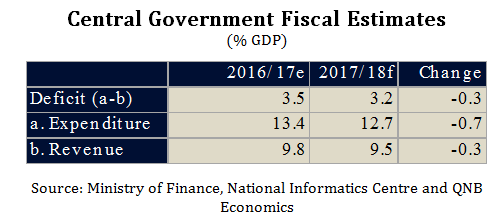

At the beginning of February, India’s central government announced its new budget for the fiscal year running from April 2017 to March 2018. The budget continued the medium-term path of fiscal consolidation, bringing the deficit down from an estimated 3.5% of GDP in 2016/17 to a projected 3.2% in 2017/18. However, in a nod to slowing economic growth momentum, the earlier, more austere, deficit target of 3.0% in 2017/18 was relaxed. Additionally, the budget tilts policy towards more capital spending and more progressive taxes, which should mostly offset any negative impact on growth.

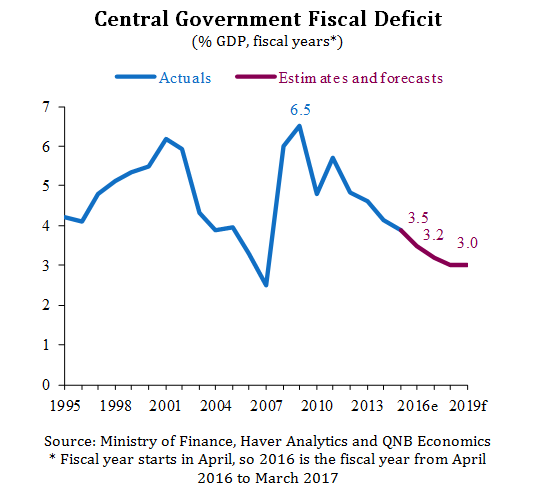

Central Government Fiscal Deficit:

During the late 1980s and early 1990s India accumulated large public debt through successive fiscal deficits. By 2003, public debt had risen to 84% of GDP, prompting the government to adopt a mandatory medium-term deficit target of 3% of GDP. After initial success, the consolidation was blown off course by the financial crisis in 2008-09, with the deficit rising to 6.5% of GDP in 2009/10.

Although subsequent efforts succeeded in bringing the deficit down, the target date for achieving the 3% deficit target has been repeatedly pushed back in 2012, 2015 and now in 2017. Following the latest budget, the central government now expects to reach a deficit of 3% of GDP in 2018/19 instead of 2017/18. For 2017/18, the budget deficit target was raised to 3.2% of GDP due to slowing growth momentum in the economy, which has been hit by weaker investment, flagging private consumption and demonetisation—the withdrawal of high denomination notes, which accounted for 86% of money in circulation.

The focus of consolidation in the new budget is on reining in current spending after it was boosted in 2016/17 by wage increases following the 7th Pay Commission—a once-a-decade review of public sector employment. Subsidy costs will also be kept down, suggesting recent commodity price increases will largely be passed on to consumers. As a result, expenditure will be cut by around 0.7% of GDP.

Lower expenditure will be partially offset by lower revenue, which should fall due to cuts to the income tax rate for low income individuals (earning USD3.7k to USD7.4k per year) as well as a cut to the corporate tax rate for small companies with revenue of less than USD7.5m. The income tax cuts will be partly offset by an extra 10% income tax surcharge on individuals earning USD74k to USD149k per year.

Despite the ongoing consolidation, we expect the impact on growth to be mitigated by threefactors.

First, the growth fallout from lower expenditure will be partially offset by a shift towards higher quality spending. The share of capital spending in total expenditure is expected to increase from 13.9% to 14.4% as part of the government strategy to increase investment to promote growth. The bulk of the capital allocations are for road, rail and metro infrastructure projects, which should benefit growth more than current spending.

Second, the revenue measures are progressive as they reduce the burden on those on lower incomes and increase the burden on higher income earners. Those on lower incomes tend to have a higher propensity to consume, which should offset some of the consolidation.

Third, the recently announced central government budget excludes state budgets, which are likely to be slightly expansionary. The states have met fiscal consolidation targets ahead of schedule and the central budget showed that they are likely to benefit from transfers of higher-than-expected tax revenue. Therefore, the states should provide a fiscal stimulus in 2017/18.

To conclude, the government appears to have successfully fine-tuned the budget to keep fiscal consolidation on track with a minimum impact on growth. We would expect the fiscal consolidation by the central government to only amount to a drag of less than 0.1 percentage points on real GDP growth. There is a risk that lower-than-expected revenue could force the government to cut spending further to keep consolidation on track. However, it is also possible that revenue could surprise to the upside as, for example, demonetisation forces the informal economy into the tax base.