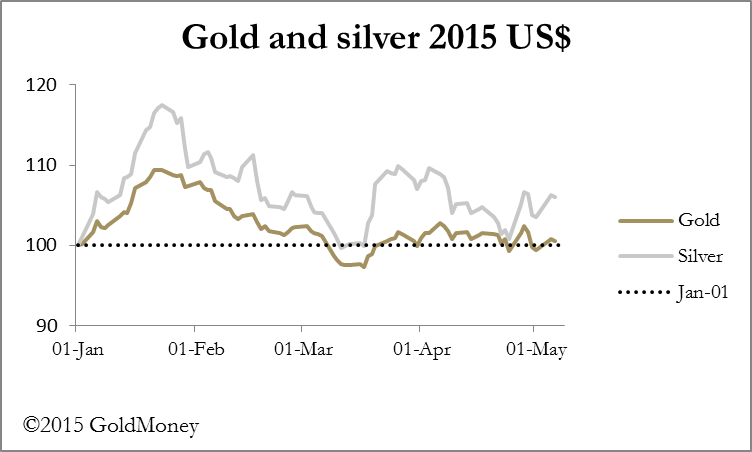

The prices of gold and silver initially rallied this week from the lows of $1170 and $15.93 respectively last Friday to challenge the $1200 level for gold and $16.70 for silver on Wednesday, before losing about half these gains yesterday.

On the year gold, is now hardly changed while silver is up 5% and is one of the best performing assets in financial markets over this timescale.

Precious metals appear to be locked into the same torpor as other markets, but there are two developing stories. At the beginning of this week government bond yields were low with negative rates commonplace, despite record government borrowing. Rational investors are barely involved in bond markets, remaining for the most part side-lined in the knowledge these distortions cannot last forever.

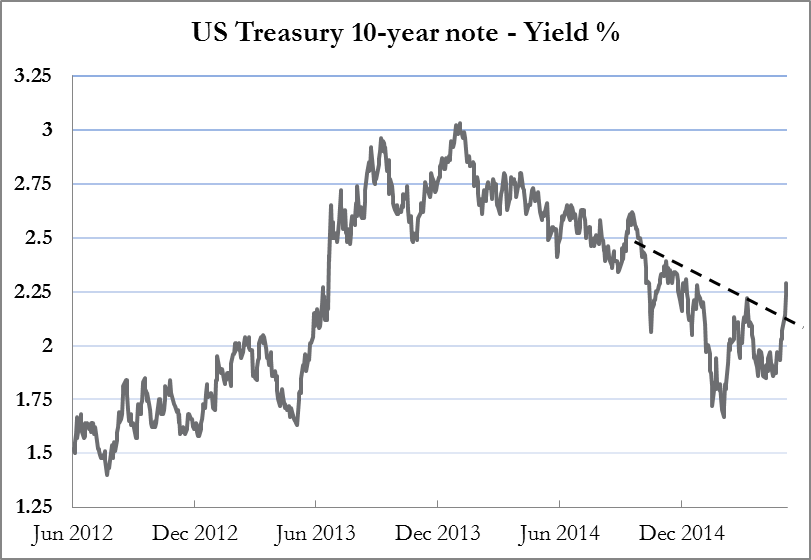

However, as the week progressed, a reaction in US Treasuries set in with the yield on the U.S. 10-Year Treasury rising sharply to 2.29%, shown in the chart below (though a reaction to 2.19% set in this morning). The dotted line is the neckline of a head-and-shoulder reversal chart pattern now completed, suggesting Treasury yields might be at risk of rising significantly higher, taking other bond markets and lower-grade bonds with them.

Since early February 10-year Treasury yields have risen 37%, implying large portfolio losses for the banks loaded up with sovereign debt. This week has seen similar rises in other key sovereign bond yields, and the losses in investment-grade and junk bonds have been correspondingly greater. The importance of this development for precious metals is that deteriorating bond markets increase the likelihood of new rounds of quantitative easing.

It could be that at last bond markets are beginning to discount the growing likelihood that Greece will default on its debt and that the Greek banks will fail. This is the second developing story, also likely to affect gold and silver.

Professor Steve Hanke of John Hopkins University recently pointed out that at the end of last year the book value of bad debts on the Greek banks' balance sheets exceeded the sum of tangible bank equity and reserves by between 22% in the case of the National Bank of Greece, to as much as 165% in the case of Piraeus Bank, with other banks falling in between these extremes. Furthermore in the last five months deposit withdrawals have accelerated, making the position worse. This being the case, not only are Greece's banks insolvent, but Greece has the potential to be Europe's "Lehman moment", with all the unintended consequences implied.

Greece's default and the failure of its banking system now seem inevitable. The remaining question is what monetary support the ECB will offer to prevent other Eurozone bond yields from rising further, and what assistance it will extend to highly-geared Eurozone banks whose own viability may be threatened.

Lastly, the UK's unexpected election result this morning initially boosted sterling. Whether or not it holds this rise only time will tell.