It’s St. Patrick’s Day, and apparently too many investors are feeling lucky.

In the last week, a cacophony of warnings erupted from financial pundits over the latest margin debt figures.

Why? Because the amounts of cash that investors are borrowing from their brokers to reportedly buy up more stocks topped $451 billion in January.

That’s the fifth month in a row that margin debt levels hit new all-time highs. (My colleague, Alan Gula, recently discussed the uptick in margin debt, too.)

We’re in “uncharted territory,” warns TrimTabs.

Andy Ash, Director at Monument Securities, fears that the surge puts us at risk for a “severe” market pullback. Indeed, it opens the possibility for the biggest margin call since the inception of the stock market.

Scared yet?

In true Wall Street Daily myth-busting fashion, it’s time to find out if there’s any legitimate reason for the apprehension. Or, more specifically, does margin debt really matter?

Think Relative, Not Absolute

They say that burgeoning margin debt should strike fear into bulls’ hearts.

After all, if investors are willing to buy stocks on margin, it signifies that they’re confident and optimistic. And as we all know, markets seldom rally when Main Street is already bullish.

It’s where Warren Buffett’s famous admonition to “be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful” comes in.

In other words, margin debt represents a sentiment indicator. And as good contrarians, we should always be wary of extremes in emotion.

Besides, if a selloff does materialize, the selling caused by meeting margin calls promises to accelerate the downturn.

It all sounds logical enough, right?

Too bad it’s entirely inaccurate…

- We’re not alone: For one thing, everyday investors aren’t the only ones that borrow on margin. So do hedge funds. They routinely use leverage to smooth out returns. And the proliferation of assets under management in hedge funds since the late 1990s obviously contributes to the increase in margin debt in absolute terms.

- Purchases unknown: Just because investors borrow money, it doesn’t mean they’re spending the cash to go long stocks. In this day of endless inverse fund offerings, they could be borrowing on margin to bet against the market.

- Easier to unwind: Thanks to the mass expansion of online trading, investors can monitor their portfolios more easily and quickly than ever before. This “real-time” access makes unwinding positions and reducing margin much more efficient.

Most important of all, we should never evaluate margin debt in absolute terms. Why? Because a certain percentage of investors always borrow against their portfolios. Consider it a constant.

Sure enough, if we examine margin debt as a percentage of total market capitalization going back to 1960, it’s stayed shockingly consistent at about 1% to 2% of investors’ portfolios.

That means margin debt is relative to the prevailing direction of stock prices. As stock prices rise, so will the amount of margin borrowing.

Therefore, the reason margin debt sits at a record high now is simply because the stock market sits at a record high, too.

When You Should Worry…

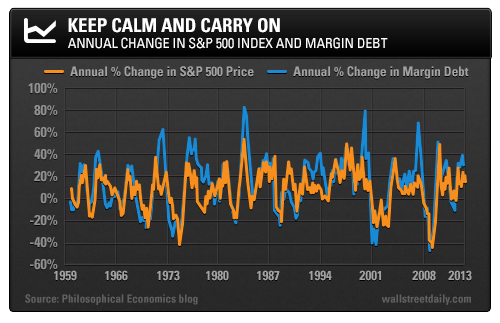

If margin debt and the S&P 500 Index historically move together, then what really matters is the pace of margin debt expansion. If it rises significantly faster than stock prices, then we should worry.

But that’s not happening right now. There are no unusual, massive spikes like we witnessed at the market peaks in 2000 and 2007. Take a look…

And if you still have lingering fears over margin debt, this should do the trick to eradicate them…

According to Bespoke Investment Group, “History has shown that record margin debt levels have not been a very good sell signal.”

To the contrary, stocks tend to rally following periods of record margin debt.

Bespoke screened for periods when margin debt levels reached record highs for five or more months. Here’s what they found…

- Three months later, stocks were up 91% of the time.

- Six months later, stocks were up 64% of the time.

- One year later, stocks were up 55% of the time.

Bottom line: Despite the latest chatter to the contrary, when it comes to timing investments, margin debt doesn’t really matter. Not if you want to be right, that is.