Memories of high inflation have faded; what does this collective amnesia mean for inflation in the future?

Inflation expectations have drifted lower because society is forgetting about inflation. Indeed, a whole generation has grown up knowing nothing but price stability. This makes it harder for central banks to hit their inflation targets, particularly in Europe where more southerly countries' inflation 'memory' has been subsumed by Germany's experience.

But this has not always been the case.

“An entire generation of young adults has grown up since the mid-1960s knowing only of inflation … it is hardly surprising that many citizens have begun to wonder whether it is realistic to anticipate a return to general price stability” – Former Federal Reserve Chair, Paul Volcker (1979)

40 years ago, Volcker worried that persistently high and rising inflation had de-anchored inflation expectations. A policy-induced recession was ultimately required to drive them back down.

We're in the opposite situation today. We've had 25 years – a whole generation – of low US inflation, depressing inflation expectations.

This explains one of today's macro puzzles: why wage inflation remains subdued despite low unemployment. Once we adjust for record-low inflation expectations, households' perceived 'real' wages are growing as rapidly as in previous economic booms.

But low inflation expectations act as a self-reinforcing anchor for nominal variables, hampering central banks' ability to hit their inflation remits.

A whole generation has grown up knowing nothing but price stability

Micro evidence suggests 'memory effects' explain the downward drift in inflation expectations.

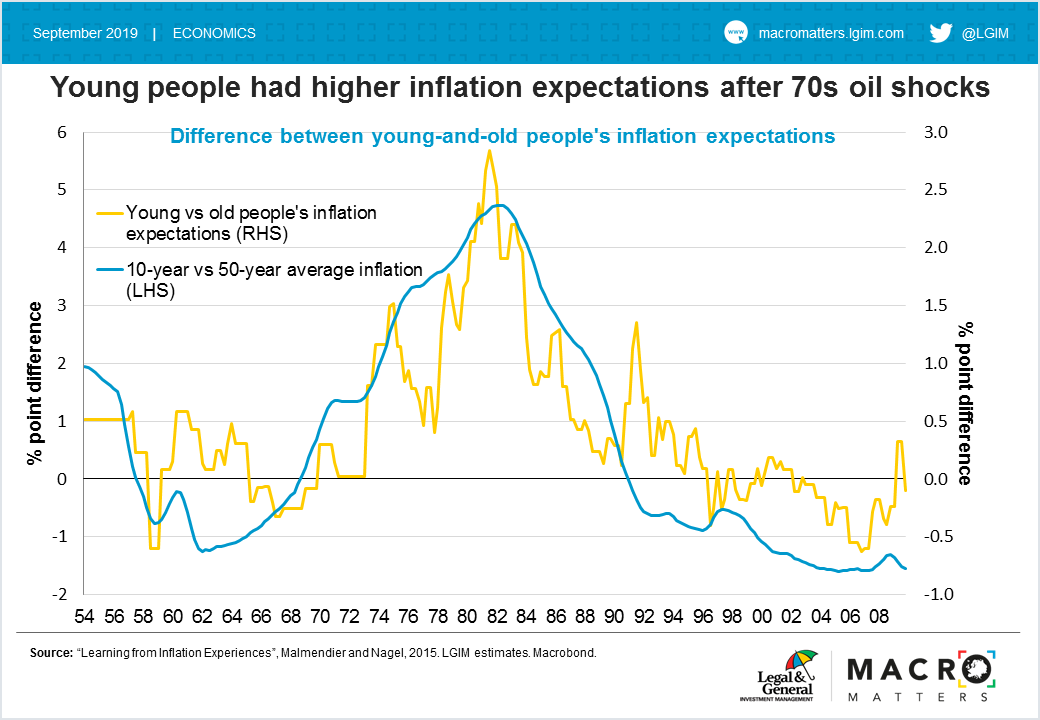

After the inflation shocks of the 1970s, younger households had higher inflation expectations than older ones. The former were scarred by the successive oil shocks while the latter still remembered the golden era of the 1960s, if not deflationary tales of the Great Depression.

To illustrate this, I have plotted the gap between 'young' (60) people’s inflation expectations in the chart below. It broadly matches the difference between short (10-year) and long-term (50-year) averages of inflation. As inflation trends above historical norms, younger people will have higher inflation expectations than older ones (and vice versa).

This suggests inflation expectations are backwards looking.

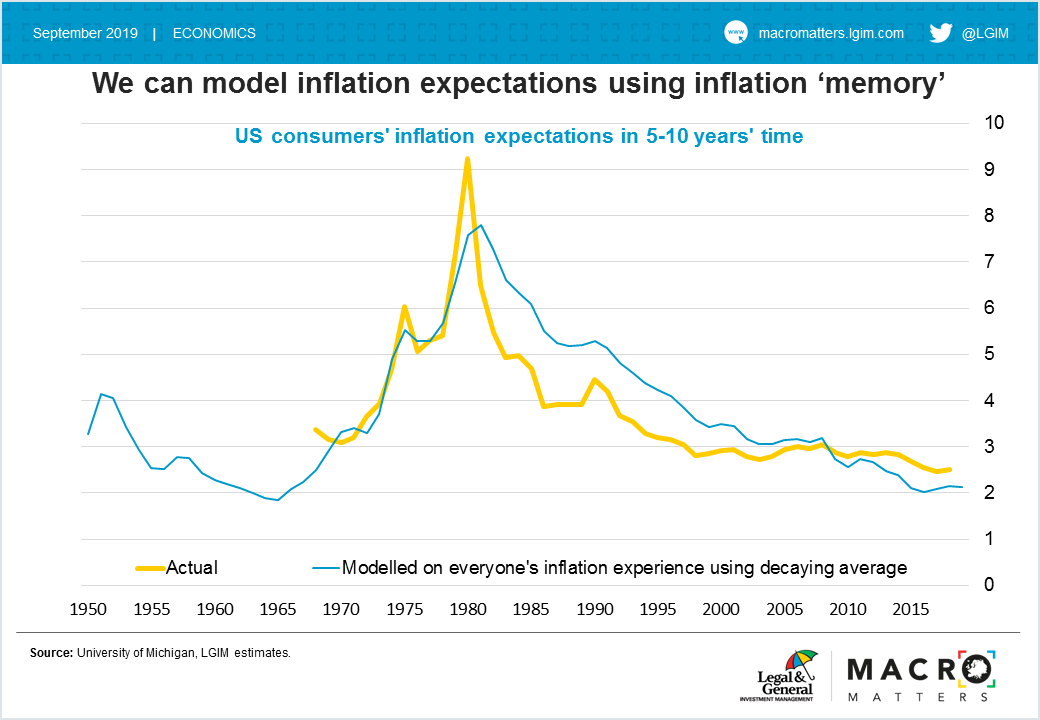

Indeed, we can track the broad contours of US consumers' inflation expectations by aggregating everyone's lifetime inflation experience.

We find a 'decaying average' works best – suggesting people put more weight on recent than distant inflation experiences.

It's not perfect. Clearly, shifts in policy credibility have a role too. But it does capture the general downward trend. Inflation expectations are drifting lower as society 'forgets' high inflation. The 2014 collapse in commodity prices augmented this.

To paraphrase Volcker, 'A whole generation has grown up knowing nothing but price stability!'

Inflation 'memory' in Southern (NYSE:SO) Europe has now converged with Germany

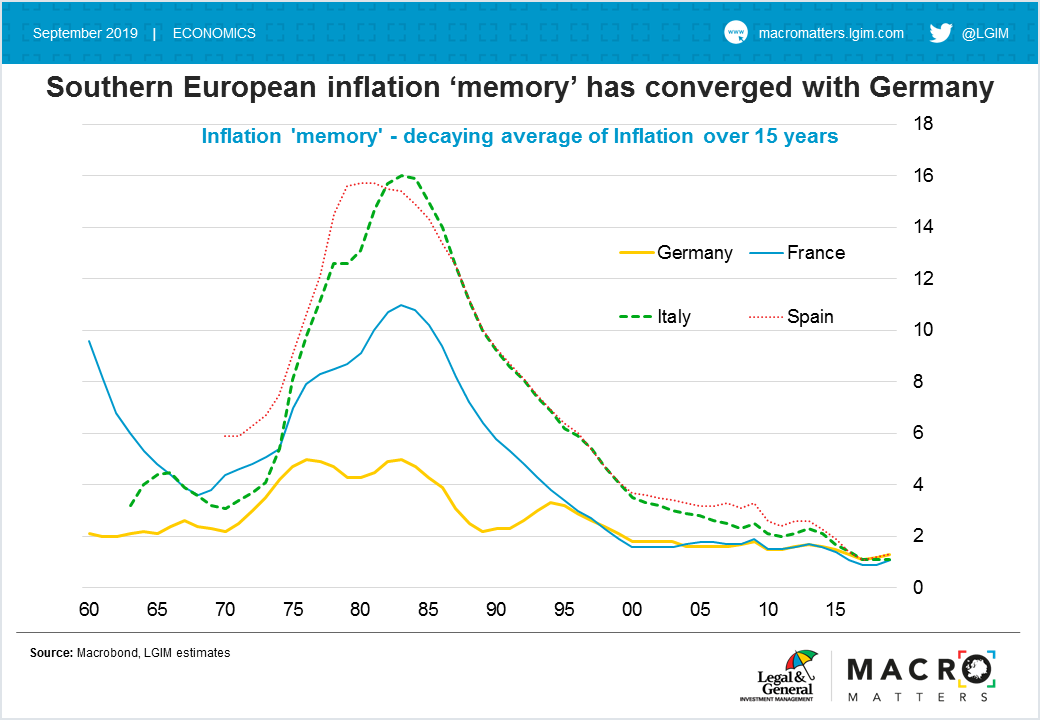

The most interesting implication of this analysis is for Europe.

It has always been a puzzle when German inflation shows only a meagre reaction to low unemployment. It probably reflects more strongly anchored inflation expectations than elsewhere because the Bundesbank did a much better job at keeping inflation under control in the 1970s.

It also helps explain the high inflation and loss of competitiveness in Southern (NYSE:SO) Europe after the euro was introduced in 1999. Spanish, Italian and Greek households still remembered the peseta, lira and drachma and periodic currency devaluations.

What's fascinating now is that an 'inflation memory' calculation for Southern (NYSE:SO) Europe has converged with that of Germany. If Spaniards, Italians and Greeks start acting like Germans, it will be extremely hard for the European Central Bank to hit its inflation remit.

We will explain in more detail the impact of this analysis on both inflation forecasts and corporate profitability in future blogs.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.