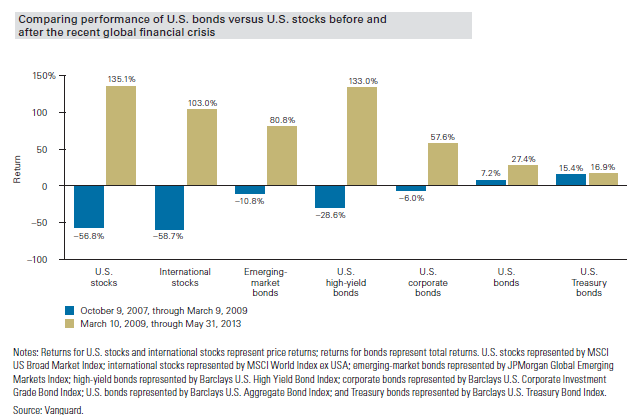

Although the rate of interest currently paid on high quality bonds today is at levels last seen in the early 1950s, investors generally allocate a portion of their investment portfolio to bonds. One reason for having a portion of an investment portfolio in bonds is the fact bonds tend to hold up well when equity prices decline. Proof of this can be seen in the below chart comparing various stock returns to different bond category returns during the financial crisis. During the worst of the financial crisis that began in October 2007, U.S. stocks fell 56.8% while the Barclay's Aggregate Bond Index and Barclay's U.S. Treasury Bond Index were up 7.2% and 15.4% respectively.

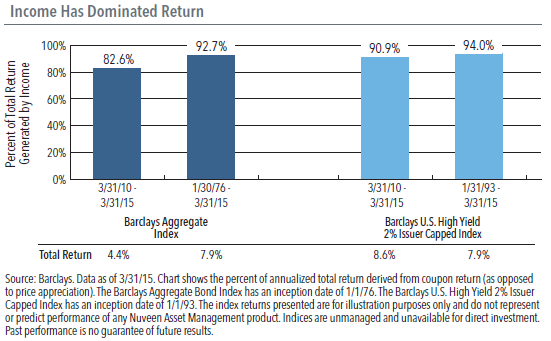

One near certainty is the Fed will increase interest at some point with it simply a question of when not if. When interest rates are moved higher (some believe a December liftoff), bond prices will decline and bond investors may be in for a bit of a surprise. A unique characteristic facing investors today is the rate of interest paid on high quality bonds is at extremely low levels. Historically, bond investors obtained some support when rates increased due to the income support provided by bonds. The below chart from Nuveen highlights the high percentage contribution to return that income has provided to overall bond returns since the end of the financial crisis and since 1976.

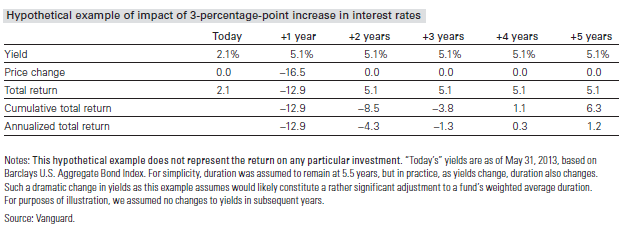

The below table from Vanguard is maybe a bit dramatic, but the table shows the impact on a bond's price return given a three percentage point increase in interest rates. One takeaway from the table is the amount of time it takes to recover the principal loss through the interest payment: over three years. This extended recovery is a result of the low interest rate starting point, 2.1% in the example and not far from today's rate.

T. Rowe Price recently opined on this same issue in a recent report. The firm notes,

"Rising rates generally result in principal declines in bond securities, and that risk is exacerbated with rates so low because investors have less of a yield cushion to offset price declines. Overall, though, the firm concluded that "since 1979, bonds have generally not done well during tightening cycles." In fact, that has been the pattern in every tightening cycle since 1963."

"In the last Fed tightening cycle from 2004–2006, when the Fed rate increased from a multi-decade low of 1.00% to 5.25%, longer-term yields barely budged. This cycle, T. Rowe Price managers expect the bulk of future rate increases to unfold in the short- to intermediate term bond sectors, causing a flattening in the Treasury yield curve (with short term rates rising more than long rates). 'I expect rates to stay fairly low even after the Fed starts raising them,' Mr. Huber says. 'Longer-term rates should stay under control because they are driven by inflation and global growth expectations, which are very modest.'"

Mr. McGuirk adds, "We don’t see any big move in long rates, and with the Fed moving gradually, you have a long time to earn the extra income to offset any principal loss."

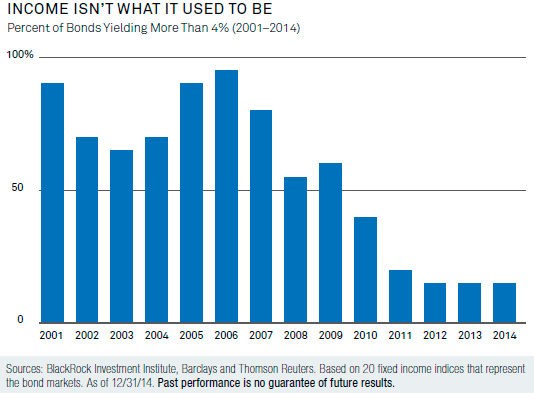

One way to shorten the time period it takes to recover the principal loss is to invest in bond's with higher coupon yields. However, given the extended length of time the Fed has kept rates at the near zero level, higher yielding bond supply is down significantly. As can be seen in the below chart, the percent of bonds that yield more than 4% is far below what was available prior to the onset of the financial crisis.

For investors, the low level of interest rates does pose a potentially higher risk to overall bond returns when the Fed does commence with a higher rate policy. The silver lining is the fact the Fed is most likely to move slowly while pushing rates higher and in small increments. A low trajectory in the rate increases reduces the downside that results from a decline in a bond's price. And lastly, as noted in the above T. Rowe Price highlight, with the low level of inflation and slow global economic growth, the longer end of the interest rate curve may increase at a much lower pace than the short end. And it is long term bonds that can experience the largest price declines when rates rise.