The U.S. government is getting closer and closer to running out of cash, for real this time.

The government has until the end of September to raise the U.S. debt ceiling, that is, the total amount the government is allowed to borrow. Otherwise, it won’t be able to pay its bills. The U.S. government spends more than it earns, and it funds the difference by borrowing.

Political infighting could result in a standoff on raising the ceiling. That would be bad news for the United States, for the global financial system and for anyone with a lingering hope that the U.S. political system is vaguely functional. But if history is any guide, it could be good for the price of gold.

One problem of indebtedness: how to borrow more

Countries have gone insolvent around 800 times over the centuries: Argentina, Puerto Rico and Greece are some of the many nations that have operated under debt repayment plans that were put into place when they were unable to make good on what they owed.

The U.S., by dint of having a global reserve currency, hasn’t had that problem. The U.S. can just print more money – an option that isn’t available to countries that don’t have a currency upon which investors place enough value.

Even if the U.S. government can print the cash it needs, though, it can’t necessarily pay what it owes, such as interest on U.S. Treasuries. The U.S. government has a limit to how indebted it can be, and it periodically hits that ceiling (as it did already in March – see below).

In the U.S., Congress (the two houses of parliament) has the power to raise the debt ceiling. But in recent years, increasing the ceiling has become more difficult. Most notably, political infighting within Congress in August 2011 nearly resulted in the debt ceiling not being raised. This reared the catastrophic possibility that the U.S. government could default on its debt.

Eventually, the ceiling was hiked. But four days after the vote to raise the debt ceiling passed, credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s downgraded the U.S. government’s credit rating from AAA to AA+.

This was the first time that the U.S. government was given a rating below AAA (the highest possible rating of creditworthiness).

The U.S. hit the latest debt ceiling in March this year. Since then, the U.S. Treasury has taken a number of stop-gap measures to pay the government’s bills.

But these financial Band-Aids can only do so much. The debt ceiling needs to be raised past US$20 trillion to cover the current debt outstanding. And if the ceiling isn’t raised by October, the government could run out of money.

But just like in 2011, infighting in Congress and with President Donald Trump could risk a new debt-ceiling hike not being passed.

And let’s not forget: As a U.S. presidential candidate, Donald Trump suggested that the U.S. government might consider negotiating a partial repayment with creditors. He later revised his remarks, but there is a risk that Trump may create the impression, which would deeply spook markets, that he views U.S. government debt as repayment-optional. Also, in his business dealings, Trump has viewed bankruptcy as a tool in the financial strategy toolbox – which is fine in the American capitalist context, but not in the global capital markets context.

How would a default affect the markets?

There’s no way to know for sure how markets would react, but it wouldn’t be good for nearly any financial market, anywhere. U.S. Treasuries are the financial definition of a safe investment.

You see, the world’s economy depends on U.S. treasuries. As the New York Times explained:

The United States government is able to borrow money at very low interest rates because Treasury securities are regarded as a safe investment, and any cracks in investor confidence have a long history of costing American taxpayers a lot of money.

Since the U.S. government can print more money or raise taxes when it needs more cash, the chances of the American government defaulting on its loans is almost nil.

But the growing possibility of default could cause investors to flee to even “safer” assets.

Where investors can find solace

During the 2011 near-default episode, one-month Treasury bill yields climbed to a 29-month high. That means that, as U.S. government debt was viewed as riskier, investors demanded a higher yield to hold it and prices of bonds fell. (For bonds, the yield increases when the price falls, and vice-versa.)

Historically, in times of uncertainty, investors and traders sell their higher-risk assets, and “flee to safety”. Usually, U.S. Treasuries are considered a “risk-free” asset. But when U.S. Treasuries themselves are the subject of uncertainty, there’s another asset that has traditionally been a safe haven: Gold.

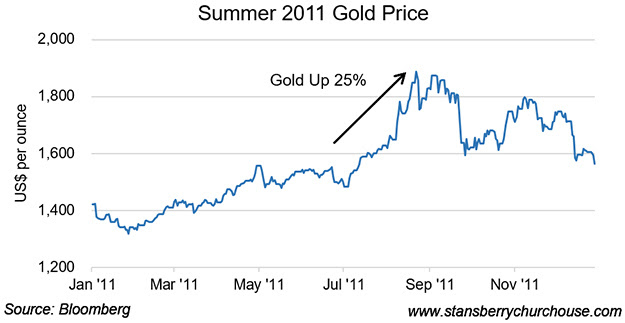

In the summer of 2011, as the political dispute that led to the standoff over U.S. government debt simmered, the price of gold soared 25 percent from early July through mid-August. On August 22, the price of gold hit US$1,889 per ounce, its highest level since 1980.

It wasn’t a coincidence that the price of gold spiked as uncertainty over the notion of “risk-free” became a topic of debate. As we’ve written before, there are lots of good reasons to own gold, it’s insurance against financial calamity. And with a debt crisis looming, now is the time to buy.

The SPDR Gold Shares (HK:2840) ETF (New York Exchange; ticker: GLD (NYSE:GLD), Singapore Exchange; ticker: O87 and Hong Kong Exchange; ticker: 2840), is one of the easiest ways to get exposure to gold.

The important thing is that you get some gold exposure today, it will help protect your wealth no matter what happens in the future.

Original post