Physical delivery premiums are a pretty accurate measure of primary aluminum metal supply. They reflect the balance between suppliers’ aspirations for the highest price and buyers’ determination for the opposite.

The setting of physical delivery premiums is, therefore, a function of supply and demand — or, more accurately, the availability of physical metal in the marketplace.

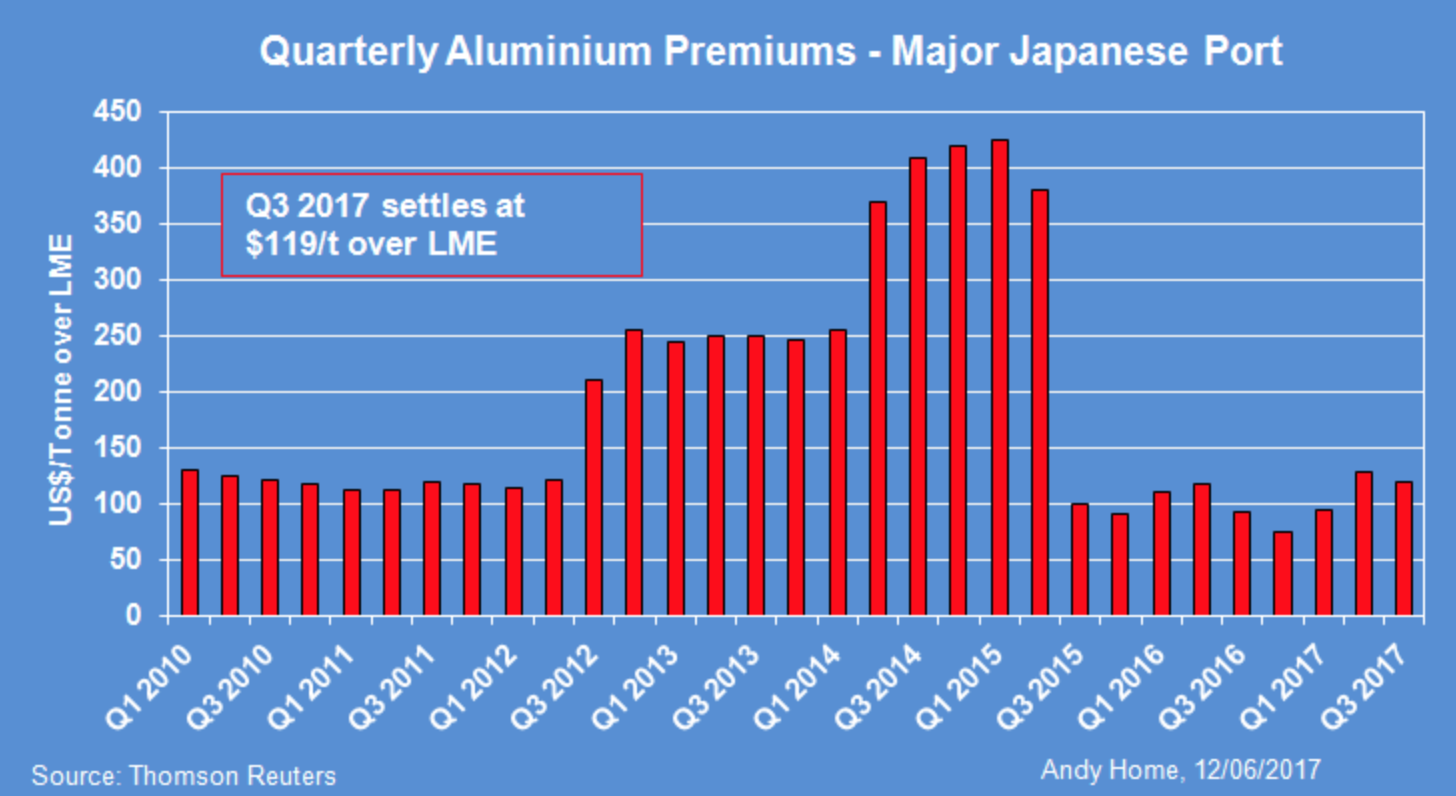

So when Metal Bulletin announced that third-quarter main Japanese port (MJP) premiums have fallen 7.4% quarter on quarter and settled for the July-September period at $118-119/ton, from $128/ton in the second quarter, it supported anecdotal evidence that, despite supply disruption from Australia and New Zealand, the Asia-Pacific market remains well supplied.

Source: Reuters

Credit for this — if “credit” is the correct term — goes in part to China’s failure to sufficiently implement supply-side reform of its aluminum sector.

The aluminum price rose strongly in the first quarter with the expectation that Beijing’s announcements regarding curtailment of excess aluminum capacity would be vigorously implemented this year.

Yet despite quite detailed policy announcements — plus the naming and shaming of smelting capacity under construction in Xinjiang that is deemed to be illegal after they failed to meet an environmental inspection — the reality is that new production continues to be brought on stream. Despite falling prices, smelters continue in their efforts to run at full capacity.

As a result, Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE) prices have fallen and downstream producers have been able to export in product areas they were previously not competitive. Aluminum flat-rolled products in particular have risen dramatically this year, displacing sales from mills in the wider region and sapping those mills’ demand for primary metal.

But the blame cannot be laid solely at China’s door.

Although aluminum stocks in the London Metal Exchange (LME) warehouse system continue to fall — dropping almost 700,000 tons last year, according to Reuters — some of that metal has flowed to the U.S., where physical delivery premiums in the first quarter were higher than in Japan.

Reuters reports first-quarter premiums at $0.10 cents per pound, or $220 dollars per ton, with those in the second quarter still in excess of $180 per ton basis of the CME’s premium contract. While LME inventory has helped ease Midwest premiums the steady outflow of metal from long-term financing deals has had a more significant impact on primary metal availability and downward pressure on physical delivery premiums, particularly in the Southeast Asian market.

This trend is likely to continue — at least until the LME and SHFE prices start tracking higher.

Reversal of the Trend — Policy Implementation

Such a reversal of the current trend is only expected to happen if China starts seriously curtailing smelting capacity, or on environmental grounds finds ways and means to curtail alumina refining, anode production and/or smelters captive coal-fired power production capacity, which has so far largely been spared recent pressure to close polluting coal-fired grid-connected power plants.

The stated aim remains to implement widespread closures from November onward, but based on China’s less-than-wholesale implementation of its current environmental review this year, doubts are beginning to be raised about how robustly closures during the winter heating period of November-February will be implemented.