Further to our ongoing theme of capital destruction, let’s look at a topic which is currently out of favor in the present market correction. Keynes called for pushing the interest rate down near to zero, as a way of killing the savers, whom be believed are functionless parasites. The interest rate has been falling since 1981.

It did not merely fall near to zero. Nor even to zero. It has gone beyond zero, into negativeland. This alone ought to wipe out the mainstream notions of how interest rates are set in our very model of a modern monetary system. You know, the rubbish about bond vigilantes, inflation expectations, real interest rates, risk, etc. Might as well add unicorns, dragons, and leprechauns!

Instead of this rubbish, the world needs a non-linear theory of interest and prices in irredeemable currency.

In recent years, rates have plunged below zero in Switzerland, Germany, Japan, and other countries. Despite the current global uptick in rates, all Swiss government bonds out to 8-year maturity have a negative yield. Hey, at least that’s a recovery from when the 20-year had a negative yield. In Germany, bunds out to 5 years are negative, as they are in Japan.

This is pathological (in fact, due to negative long bond yields in Switzerland, Keith wrote a paper arguing that the Swiss franc will collapse).

As an aside, we note that when people hear our arguments, they go through a process akin to the well-known stages of grief. These include denial, anger, bargaining, and then finally acceptance and hope. It is much easier to think about rising quantity of dollars, and the presumed linear effect of rising consumer prices. And more pleasant, too.

Yields Must Fall

What does a negative yield have to do with capital destruction? As Keith argued in the heat death of the economic universe, yields must keep falling in order to make more and more debt serviceable. If the rate of interest does not keep falling, then the extant debt must be wiped out. Since everyone’s money in our system is someone else’s debt, that means a wipeout of money itself.

Something extraordinary occurs when you cross what economists blithely euphemize as “the zero bound”. Investors are doomed to lose some of their capital. It should not be controversial to say that if you buy a CHF1000 bond and get back CHF999, then you have lost 1 franc. Now imagine that this is occurring to everyone, across the entire economy. And the trend is downward.

Regime apologists should not dare to tell the investor that, “well you see, you got a positive real interest rate, so your purchasing power increased. You lost money (or what everyone believes to be money). But hey the booby prize is that what you have left will buy more groceries.”

We expect that it will be controversial to say that negative interest allows borrowers to destroy capital, unseen. In a normal world—that is one where Keynes and Friedman never convinced us to adopt government debt as the risk-free asset, and central bank credit paper backed by that debt as if it were money—no enterprise could borrow and repay less than it borrowed. No one hands over an ounce of gold to get back 0.99 ounces (if you disagree, please call us, we will borrow as much as you want to lend!)

However, we’re not in a normal world. We’re in a Keynes-Friedman world, and that irredeemable currency is believed by most people to be money. And rates are sinking (yes, we know, not in the present correction, the latest of many in the 37-year trend), and now in a number of countries are below zero. Don’t worry, ‘Murrica, we’ll get there too—last.

In a normal world, borrowers cannot run a loss-making enterprise indefinitely. Though even in positive-rates America, they can get away with it for a long time if the Fed creates a permissive credit environment.

However, Fed or no Fed, losses are written on the financial statements. A business that destroys investor capital at -1% per year will run out of cash, sooner or later. This is in a normal world. What if the world is not normal?

Let’s consider that. Losing Corp. loses money at -1% but borrows at -2%. Earnings before interest is negative. But after interest, “earnings” is positive. Unlike the former case where the company reports loses while other companies are presumably reporting profits, and thus the money-losing company will eventually repel investors, in this case it is sustainable. At least so long as the interest rate is negative. Which it will be (and falling) for all the reasons we have been writing for years.

Liquidating Civilization

Of course, it’s not sustainable. It will end, but the central banking regime has made it much more difficult to liquidate losing businesses (while ensuring more and more businesses will lose). Large scale business liquidation can only occur when it is no longer possible to slowly liquidate civilization.

Let’s defend that statement. The interest rate is the single most important price in the economy, because every other price and every investment and every enterprise depends on it. And the central banks have created a system which has driven it down to zero and beyond.

The interest rate is the expression, in the market, of a universal in the human condition. Time itself (we will revisit this idea in a future essay).

When interest sinks below zero, it means that the return to be earned on capital is negative. It means all savers are doomed to slowly lose their capital. It means any other better opportunities have, for one reason or another, gone away. No one would lend at -2% if he could get +3% obviously. So the market being moribund at -2% means the marginal enterprise sees no better opportunity. They are willing to borrow only if the rate is that or lower.

As an aside, this is a good way to think of the dynamics of a falling interest rate. There is little demand for credit, other than on a downtick in interest rates.

By the time it gets to the terminal phase, where businesses are borrowing at -2%, the marginal business is not able to bid higher than that. It does not want credit, except when the price is -2%. A business will always seek to borrow at lower than its return on capital (or else there’s no point). A bid of -2% means the business wants credit to finance wealth-destroying activities.

There is no mechanism to deprive one particular wealth-destroying enterprise of capital, when large numbers of them are losing. There is not one bad company showing losses on its financial statements, slowly running out of cash. There is a whole economy full of them—showing profits! If something is profitable, businesses will scale it up until it no longer is.

In a free market, only wealth-creation is profitable. But in this terminal stage of the unfree market based on the forced feeding of credit, borrowing at -2% and destroying capital at -1% is profitable. This trade will be scaled up.

Perverse Incentive → Perverse Outcome

Inevitably, people will blame free markets, business, and the profit motive itself. They will not question the perverse outcome that comes from the perverse incentive of a falling interest rate and the heat death of the economic universe. So the for-profit business will take the blame that should go to the Fed and the legal tender laws and the rest of the whole edifice of our monetary regime.

No matter, one thing is for sure. If it is profitable to destroy, if the profit scales with no corrective negative feedback loop, if the Fed has long since substituted pennies for every fuse which could prevent this conflagration, then destruction will proceed. We will cannibalize the capital on which our civilization was build. All the while, reassuring ourselves with every macroeconomic aggregate in the statist’s playbook. GDP will show growth (though marginal productivity of debt will decline). Inflation, so called, will be tamer and falling. There is one possible exception.

Keith has been saying for years that there is no extinguisher of debt in the system. Therefore, debt necessarily grows exponentially, as the accrued interest is added to the debt. And even faster, if you want what passes for growth.

Negative interest rates provide a compensatory force. If debts in general pay back less than what was borrowed, then debt can decrease. However, this is not what we would call “extinguishing” debt! A better way to think of it is a partial default. If you lend $1,000 and get back nothing, then that is a total loss of capital. You write off $1,000. If you get back half, it’s a partial default and you write off $500. Negative interest should be thought of like this.

Default is never good, but it’s particularly bad in a system that has long depended on perpetual growth of debt. Not to mention a system with falling profit margins of financial intermediaries (a consequence of falling interest rates), and hence provided both the motive and the means of increasing leverage. The key to keeping the game going will be to make sure that assets remain greater than liabilities. Since there is a steady erosion of assets in nominal terms, the trick is to ensure nominal capital gains outpaces this loss.

In other words, you can borrow to carry an asset, even if there is a negative cash flow, so long as asset prices are rising. People do this in real estate all the time (and call it “investing).

It gets trickier, because rising bond prices mean falling interest rates. The rate must go deeper into negative territory. Which accelerates the nominal losses. No doubt, the central bankers will boast about how clever they are, how much skill the technocrats possess. Until the end.

In the end game, runaway paper losses are in a race against runaway destruction of real capital assets. As horrible as it will be, if the Fed loses control and the paper losses bring the dollar down, this is the less bad outcome. That’s because the alternative is to keep eating the seed corn, keep consuming capital until we actually run out. Total capital destruction would be worse than paper currency destruction.

One question arises from this discussion, which we shall leave to next week: do negative rates make it possible for the quantity of dollars to decline?

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

This week, we saw a tweet from a prominent goldbug. He said, “Russia added another 9 tons of gold to its reserves in March. The hits just keep coming.”

How many errors in this short quip? We count six, exactly one error for every two words.

One, we call this the fallacy of the famous market actor. Russia is famous. Its purchase of 9 times is therefore imbued with meaning, that the sale of those same 9 tons is not given. Because the sellers are not famous.

Two, the concept of stocks to flows measures the abundance of a commodity. It is not a measure in terms absolute tonnage, which would be useless. It looks at how much of the good is accumulated. Virtually all of the gold ever mined in human history is still in human hands. Russia’s purchase is merely the shifting of a very small percentage of total stocks from one corner of the market to another. Hell, 9 tons is a small fraction of 2017 mine output let alone 5,000 years of accumulated mining output.

Three, this goldbug speaks often of a change in the monetary order, hopefully and presumably one based on gold. But this bit about Russia shows the ambiguity of most gold bugs. Buy gold because of new monetary order and because its price will go up. Huh? If the dollar is collapsing, what meaning does the price of gold measured in dollars mean? Conversely, if one is promoting a new monetary order, why promote Russian gold buying to promote a quick trade to make a buck?

Four, this purchase by Russia is bullish (remember, it’s not a sale by smarter people to the dumb money of central banks). Is all news bullish? 2011-2016 would suggest it isn’t.

Five, a gold standard is not about central banks buying gold. Or loading up on gold. Or having “enough”. There is no amount of gold that could ever conceivably be enough for the Russian central bank to have, to defend a gold price peg. All rubles (and dollars, pounds, etc) did not begin life as gold deposits. They cannot retroactively be declared to be gold-redeemable.

Finally, the ruble is not exactly in a rising trend. So whatever “hits’ he means, it is not a “hit” to the US dollar. Which the goldbugs want to hear, in the dualist world of gold going up vs. seeking out good news about the dollar going down because it’s good for gold.

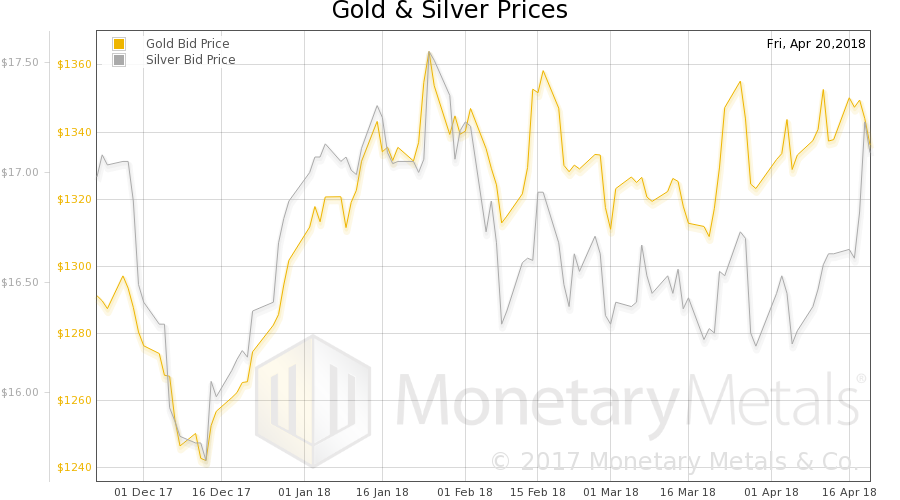

That said, gold fell ten bucks, but silver rose about half a buck. Silver bugs have begun to (more aggressively) say that the rally’s back on. We will look at the fundamentals, but first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

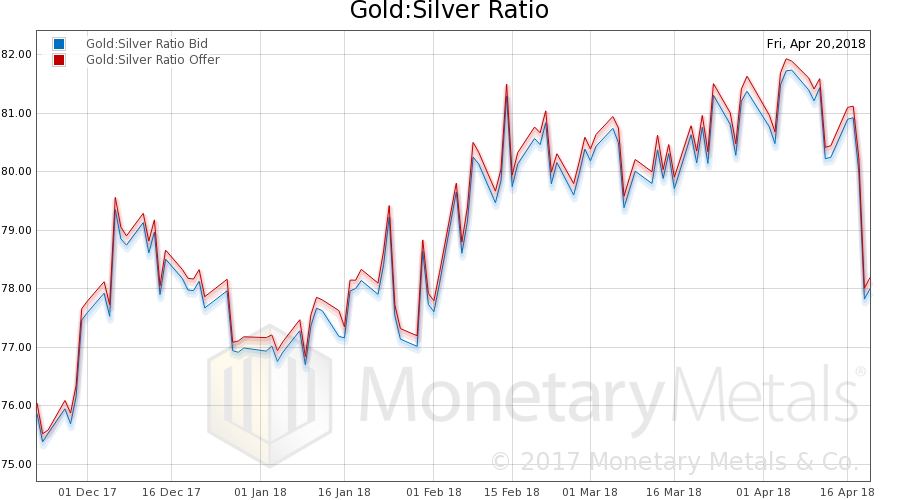

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio. Big drop in the ratio.

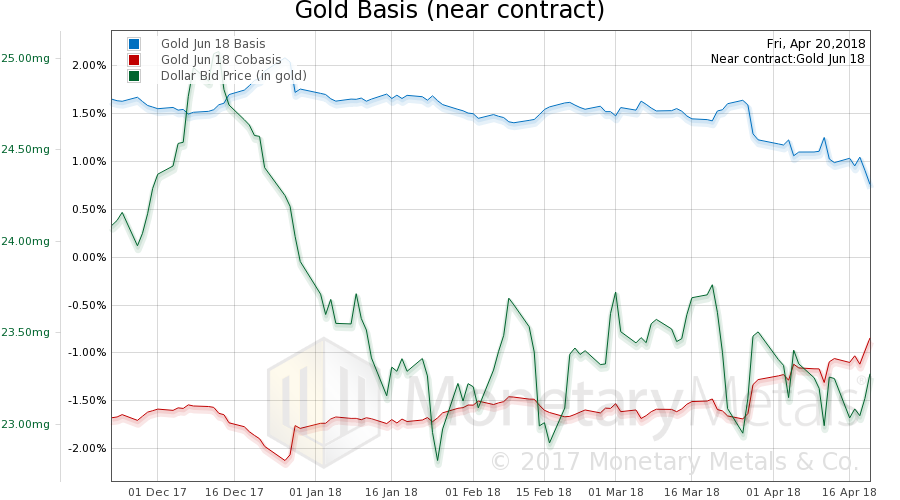

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

There was a small increase in the scarcity of gold (i.e. cobasis, red line), as its price fell. The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price fell $2 this week to $1,507. Now let’s look at silver.

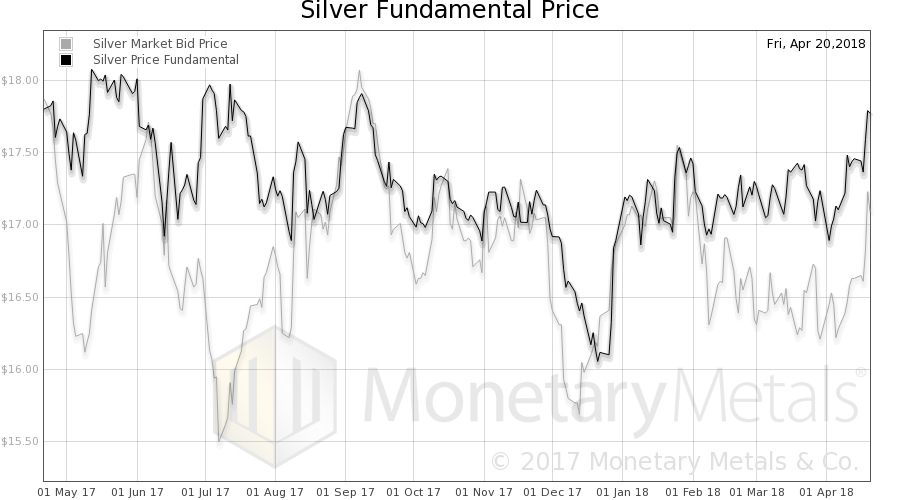

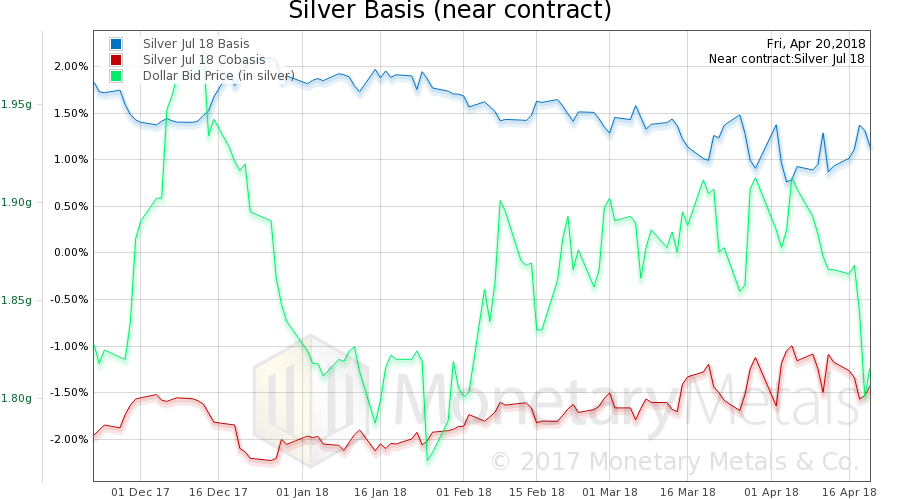

Silver’s scarcity fell, however unlike in gold the price of silver was up considerably. Much of this buying was buying of metal, rather than the typical in recent years of futures contracts. The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price rose 31 cents to $17.77.

Here is a chart of the silver fundamentals for the last year. Has the silver fundamental had a breakout? We would want to see more evidence before pronouncing this. Heck, even the market price has not surpassed its level from January yet.