Forward guidance is a new phenomenon in the UK. Mr Carney introduced us to it for the first time in the Summer of 2013, bringing the concept with him from Canada, having used it in 2009 as Governor of the Bank of Canada.

Forward guidance was used by the Fed for the first time in 2008 but by Scandinavian central banks even earlier – Norges (Norwegian) Bank began in 2007 and the Riksbank (Sweden) started in 2005. However, these latter two have a different approach to forward guidance than the Americans or Brits.

At set times throughout the year both Norges Bank and the Riksbank publish a ‘policy rate path’ forecasting the level of the policy rate expected by the majority of the Executive Board (of the central bank) over an, approximately, three year forecast period.

These banks also publish a range of economic forecasts – growth; inflation and unemployment rate. This type of forward guidance is rightly considered one of the most explicit in the world, however, its essence is more illustrative than one would think at first blush.

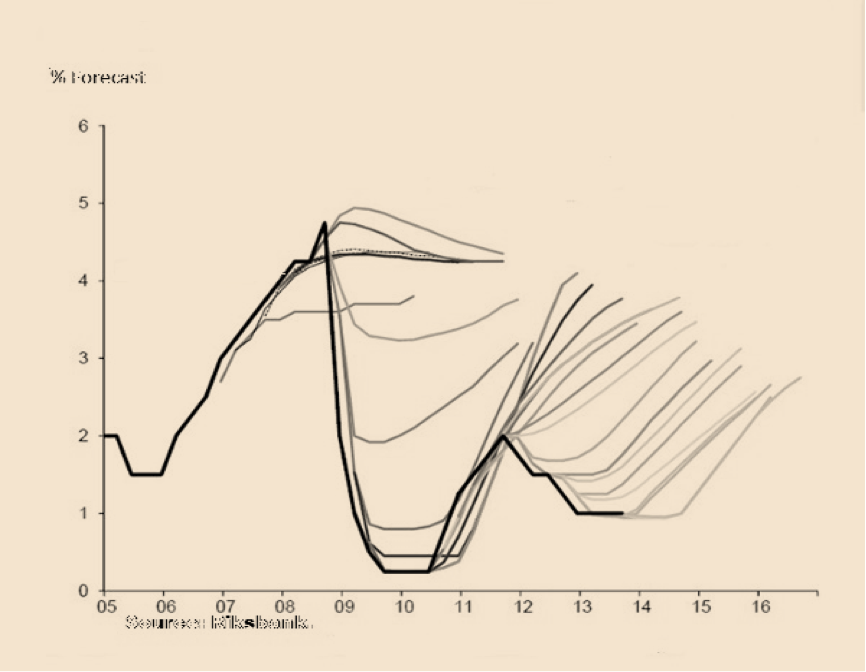

The policy rate path ‘forecast’ is a conditional estimate of future policy rates – based on the economy and market conditions – not a commitment. Below we see the various policy rate paths issued by the Riksbank, in contrast to the actual path (dark line) taken over time.

As may be seen, rate path guidance is not always the most enlightening of exercises. Having said that, studies (for example ECB Working Paper Series No. 1098 / October 2009) have found weak evidence to suggest that a publicised interest rate path reduces the volatility of short term interest rates, implying that predictability of future interest rate movements is enhanced with the publication. This should be of interest to forex traders, both from the point of view of accurate forecasting and reduced volatility in the market.

Now let us turn to the Bank of England. Would there be a benefit to the BoE if it were to take up this method of forward guidance? The Old Lady will be concerned primarily with three things:

I. Does publication of an interest rate path enhance the short-term predictability of monetary policy and help to avoid policy surprises?

II. Does the introduction of an interest rate path help to anchor long-term inflation expectations?

III. Does quantitative guidance in the form of interest rate path publication improve central banks’ leverage over the term structure of interest rates?

There is, as yet, no evidence that the first two questions above are answered in the affirmative. Policy surprises are, by definition, born of unexpected circumstances and these are not influenced by the decision to publish an interest rate path. Long-term inflation expectations are formed by a host of financial data reports which are little influenced by a publication such as the one under consideration.

Although no study has ever concluded that publishing the interest rate paths does provide stability, however in most of these cases we only consider proof when we want to attack or challenge a current policy and so far there has been little change to this approach since 2005 so something must be working.

The third question, it seems, is answered with a ‘Yes.’ This may be considered an important point by the BoE for the following reason:

From the communication perspective, this may allow a significant influence on longer-term bond yields. For example, assume that a central bank wishes to guide yields in a specific direction and that experience has shown that they are able to move the markets more when they publish an interest rate path. If that were the case, then the central bank would be more successful in steering the markets by quantitative forward guidance (rate path publication) than by means of a speech.

However, now comes the question – will the Old Lady take up this style of forward guidance? The answer (in my opinion) is ‘Doubtful.’ The reasoning behind that sentiment is as follows: The BoE likes (under the present Governor) to tread the line between flexibility of purpose and perceived certainty of intent.

An example of this is that although Mr Carney brought forward guidance to us with a quantitative twist (remember his comments on the unemployment figures), he still ‘hedged his bets’ considerably. Mr Carney’s letter to George Osborne, on 7 August, 2013, tells the Chancellor of the Exchequer that the MPC has decided that “…explicit forward guidance can enhance the effectiveness of the [Bank of England’s] exceptionally stimulative monetary stance”.

Whilst the overall tone of the letter suggests that interest rates will remain low and asset purchases maintained until unemployment falls to 7.0%, Mr Carney adds:

“The guidance will cease to apply if material risks to price stability or financial stability are judged to have arisen.”

And so he is essentially saying that what he intends to do may be changed at any given time with respect to prevailing circumstances. Wait and see, Mr Chancellor!

In the minutes of the MPC’s October meeting, it was noted that the headline unemployment rate has fallen to 7.7% but remained well above the 7.0% forward guidance threshold. The minutes continued:

“The recent reduction in the unemployment rate indicated that slack in the economy was, as anticipated, being eroded as activity picked up. If anything, that was occurring a little faster than envisaged at the time of the August Inflation Report although it remained unusually difficult to gauge the effective degree of slack in the economy.”

Here we see the caveat of ‘measurement difficulty.’ Thus it seems that a publication of interest rate paths may not sit well with the Old Lady. It would be too quantitative and give the odour of certainty to her statements, even though she will retain full discretion; as do the Scandinavian central banks.