For the past 10 years or so, bad news in China was usually good news. Growth shocks triggered sizable stimuli, leading to asset price rebounds in China, emerging markets and the world more broadly. But this regime is now a thing of the past.

Take the trade war. Tariffs announced by the U.S. potentially reduce Chinese growth by one percentage point, not counting second-round effects on confidence and financial conditions. Despite this large shock, Chinese stimulus announcements have been few and far between.

In addition, the leadership has explicitly ruled out using the property sector to spur the economy. The sector was part and parcel of every previous stimulus package as it accounts for 30% of activity when including upstream industries.

Most importantly, the scope for further Chinese efforts has shrunk markedly after a decade of easy policies. Debt has surged by 112% of GDP over the past decade, the current account is moving towards a deficit from a 10% surplus in 2007, and house prices look increasingly frothy.

China's room for policy manoeuvre is now narrower and the world is a less friendly place

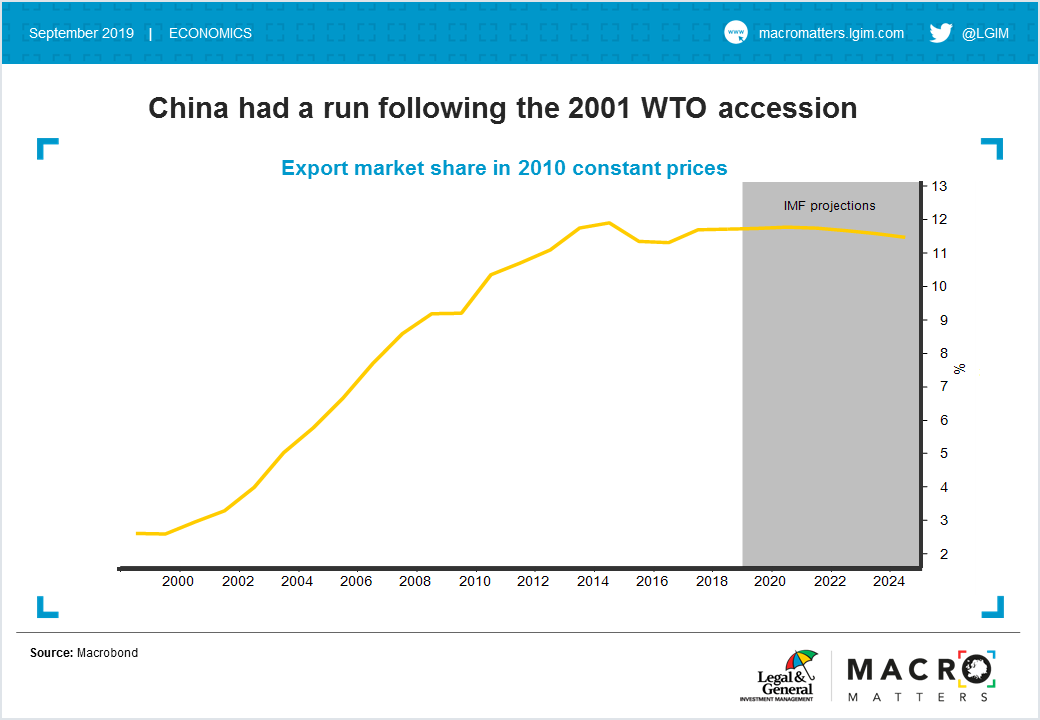

To put this into the broader context, China had a great run following its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. Over the subsequent decade, China consistently surprised to the upside. The war chest it accumulated during these fat years helped it sustain momentum well beyond the global financial crisis. However, China's room for policy manoeuvre is now narrower and the world is a less friendly place. Ignoring policy constraints now could set China up for a crisis down the road.

Financial stability has likely been elevated to an issue of national security

These risks have taken on a new significance with the advent of the US-China trade conflict. A Chinese financial crisis would surely be a boon for the security hawks in Washington. In turn, financial stability has likely been elevated to an issue of national security in Beijing, tilting the scales against stimulus and growth.

With leverage becoming less of a shock absorber, growth is set to become more volatile. It may not show up in GDP numbers, which are already heavily smoothed, but could become visible in higher-frequency indicators such as production or purchasing managers’ indices. Also, don’t expect the change to happen overnight. China likes to do things gradually: in the words of Deng Xiaoping, to “cross the river by feeling the stones”. Stimulus will be administered, like the recent reserve requirement ratio (RRR) cut, but to a lesser extent than in the past.

In many ways, we expect the current episode to resemble the renminbi (RMB) regime change of 2014. For eight-and-a-half years the Chinese currency had only strengthened but, once the current account surplus reached normal levels, the RMB stopped appreciating and moves became more two-sided.

Many were caught off guard and at the time the change was not that obvious. But, with hindsight, something had fundamentally changed. We are again at such a turning point.