On October 22, Moody's downgraded the state of Illinois GO and sales tax debt from A3 to Baa1. To summarize Moody's explanation, the state's financial situation has deteriorated during the 2014–2015 budget cycle, more so than in the previous year, because of the sunsetting of Illinois' temporary flat 5% income tax rate to its current 3.75% (still up from the original 3% prior to enactment). Illinois' budget deficit is expected to be $6 billion in 2016, as a result. Its backlog of unpaid bills is still $6.9 billion. To put these figures into perspective, the state's general fund revenues were $33 billion for the fiscal year ending 6/30/15, so there is a 20% hole in the state's budget that it must somehow fill.

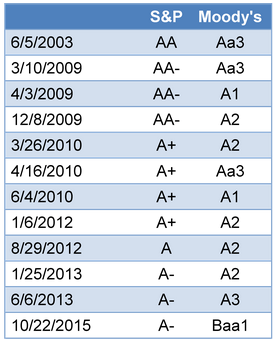

In defense of Governor Bruce Rauner, who ran on a platform of not extending the temporary tax, the greater revenues from 2011 to 2015 did little to fix the state's financial situation. Since then, the total unfunded actuarially accrued liability for the state's four pension plans has increased from $82.2 billion to $111 billion, while the plan's funded ratio has declined from 43.4% to 39.3%. Moody's states that Illinois "is still extremely vulnerable to another downturn, barring unexpectedly strong and swift corrective actions." The chart below shows ratings agencies’ actions in response to the deterioration in Illinois credit quality since 2003.

In Illinois there is an ongoing budget stalemate between the state's Republican governor and its Democratic chambers of legislature. Do we see value in Illinois paper? Not at this point. With long Illinois paper still trading sub-5%, the market is not pricing in the likelihood of one of the following outcomes:

1. The credit could get downgraded in the interim.

In Moody's annual default study, one of the salient features of municipal bonds is the extraordinarily low default rate on Moody's-rated obligations. Over the last 40 years, the percentage of municipal bonds to default has been 0.14%, versus 11.4% in corporates. The risk with any municipal bond is not so much missed payments but the market loss from "headline risk."

We discuss this unique risk to the municipal bond asset class in our top-selling book, Adventures in Muniland: A Guide to Municipal Bond Investing in the Post-Crisis Era, which you can purchase by clicking HERE.

Moody's and S&P have indicated they intend to downgrade to junk those states whose pension systems revert to pay-go funding. A pay-go funding structure is tantamount to a scheme whereby payouts of benefits are made from pay-ins. In state government, this is done on an intergenerational basis whereby current benefits earned decades ago by current retirees are paid for by taxpayers in the present. When the funds in the system deplete, the ratings agencies will likely downgrade Illinois to junk. (As an aside, the term "Illinois pension fund" really refers to the average funding level of the state's four funds; for instance, the state legislature's pension fund has only 17% of the assets needed to pay retirees.)

2. The federal government may come to the rescue.

Immediately following the financial crisis, in the 2009–2010 fiscal year, the collective budget gap of the 50 states was $191 billion. From 2009–2011, the federal government transferred $140 billion to state governments, mostly as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. While this transfer was largely a result of the federal government's expansionary fiscal policy in the aftermath of the Great Recession, the federal funding paid for a large percentage of the increase in demand for welfare programs and open-ended entitlements, giving states discretion in their use of the funds. During the same period, in spite of the unprecedented federal funding levels, states made large cuts to public education, both K–12 funding and investment in infrastructure, to improve budgetary flexibility.

The federal government effectively bailed out the states and would likely do it again in the case of Illinois. While this would be an absolute last resort after all other solutions had been attempted and exhausted, there is still a very large "federal government put" implicit in state municipal bond debt.

3. Funds may be reprioritized to pay debt service.

States can reprioritize their payment waterfalls to prioritize debt service over most other expenditures. Illinois has stated publicly in the last week that it has the constitutional flexibility to do this, and has done this, at the expense of its pension beneficiaries and vendors (hence the rapid growth in both of these liabilities). Other states, such as California, must prioritize other expenditures such as K–12 educational funding. States need market access to fund operations, capital expenditures, and timing gaps between revenues and expenditures. In this regard, in 2014, Illinois's consolidated revenues from all non-business activities of $63.4 billion dwarfed its debt service payments of $3.6 billion.

Our forecast is that spreads will continue to widen on State of Illinois debt as the ratings agencies continue to downgrade the state. As investors, while we view repayment in time and in full as close to a "sure thing," investors playing in the space expose themselves to loss due to headline risk.

At Cumberland, we do not purchase State of Illinois or Chicago debt for our clients, insured or uninsured. The risks are asymmetric and impossible to predict. Opportunity in municipal bonds can be found in the investment-grade space where credit risk is very low relative to corporate bonds and where tax-exempt yields approximate those of taxable US Treasuries.