The great economic historian Charles Kindleberger described a bubble as follows:

“What happens, basically, is that some event changes the economic outlook. New opportunities for profits are seized, and overdone, in ways so closely resembling irrationality as to constitute a mania. Once the excessive character of the upswing is realized, the financial system experiences a sort of ‘distress,’ in the course of which the rush to reverse the expansion process may become so precipitous as to resemble panic. In the manic phase, people of wealth or credit switch out of money or borrow to buy real or financial assets. In panic, the reverse movement takes place, from real or financial assets to money, or repayment of debt, with a crash in the prices of commodities, houses, buildings, land, stocks, bonds – in short, in whatever has been the subject of the mania.” (Manias, Panics and Crashes, 1989)

In recent years, we have seen this process occur with respect to internet stocks (late 1990s), the nation’s housing stock (mid-2000s), and twice with respect to corporate credit and the high yield bond market (2001-2 and 2008).

Last weekend, we were warned that the high yield bond market is experiencing a bubble. Unfortunately, the warning was completely misplaced despite coming from a highly respected source, MacroMavens’ Stephanie Pomboy. Ms. Pomboy argued in Barron’s that high yield bonds meet “all the standard criteria of a bubble.” I don’t know which criteria she is referring to, but I would respectfully suggest that Ms. Pomboy reread her Kindleberger. The reality is that today’s high yield bond market exhibits none of the characteristics of a bubble.

Investors’ desperate search for yield in today’s zero interest rate environment could lead them to look for yield in all the wrong places. The Federal Reserve’s zero interest rate policy has now persisted for four years and there is no end in sight. Today, however, the high yield bond market is not one of the wrong places to look for yield, as it has been so many times in the past. There are several reasons why that is the case.

The most important reason is that corporate default risk today is extremely low today. It is also likely to stay that way. Thus far in 2012, the corporate default rate is below 3%, far less than the historical average of 4.6%. High yield issuers have strong cash balances, healthy working capital positions, and manageable debt amortization schedules. Prior to earlier high yield bond market collapses in 2001 and 2009, there were many warning signs that corporate defaults were going to skyrocket. The market did not disappoint. In 2001, defaults reached 10.5% and in 2009 they hit 13%, the highest corporate default rates the U.S. had seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Conditions today are a far cry from then.

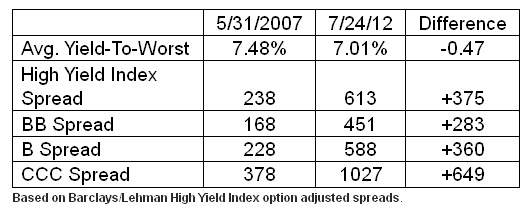

The second reason why the high yield bond market is not in a bubble is that valuations are not unreasonable. Ms. Pomboy argues that “spreads are hovering at 2005 lows” (Barron’s, July 23, 2012, p. 33), but that is simply not true. In fact, spreads are much wider today than they were in 2005.

Ms. Pomboy is certainly correct to point out that the absolute yields on high yield bonds are uncomfortably stingy today. As hybrid securities that combine the characteristics of equity and debt, high yield bonds should offer investors an appropriately high return for taking equity risk. That risk, however, is much higher in a CCC-rated bond than a BB-rated bond. But CCC-rated bonds offer average yields of 11% today, which compares very favorably with what is on offer from many stocks today. That is certainly not the sign of a bubble. This is particularly true with respect to the CCC-rated bonds of large leveraged buyouts that date from the mid-2000s. Moreover, despite their low ratings, many of these bonds are attractive investments today for too many reasons to outline here.

The third reason that high yield bonds are not experiencing a bubble is that there are few signs that the new issue market has reached the silly season. In fact, the quality of new bond issuance is far superior today to what it was in the periods that preceded previous market crashes. The internet bubble of the late 1990s-early 2000s was fueled by telecommunications and internet companies selling debt, while the private equity bubble of the mid-2000s was fed by the large buyout firms. In both periods, these borrowers flooded the markets with tens of billions of dollars of highly speculative deals of dubious credit quality: bonds rated CCC+ or lower; holding company bonds; pay-in-kind or toggle notes (bonds that have the option of paying interest in cash or kind); dividend recapitalization financings; and covenant light bank loans. Most new issuance today is related to the refinancing of existing debt. Very few new LBOs are being done, and telecommunications, technology and internet companies are financing themselves in the equity markets, where they belong.

Those familiar with my track record and writings know that I have never been an apologist for high yield bonds. In fact, I have spent much of my career warning investors about their risks. My approach to investing in this asset class is different than that of most managers based on my dour view of these securities and the private equity firms that are among their largest issuers. In both 2001 and 2007, I warned investors to exit the high yield credit market in my newsletter, The Credit Strategist. I do not feel that way today for the reasons outlined above. There are significant risks facing investors today, as David Kotok has so eloquently warned in his writings on the European debt crisis. For once, however, those risks do not come from weak credit quality or overvaluation in the U.S. high yield market. Ms. Pomboy was incorrect in her assessment, and the last thing the high yield bond market needs is its own Meredith Whitney moment.

BY Michael Lewitt

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Polski

- Português (Portugal)

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Junk Bonds Are Fairly Valued

Published 07/27/2012, 01:54 AM

Junk Bonds Are Fairly Valued

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.