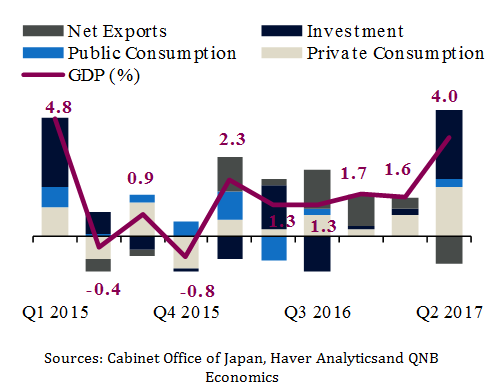

Japan is enjoying one of its longest growth streaks after decades of economic malaise. Earlier this month, the release of Q2 GDP data revealed that growth rose to 4.0% on a quarter over quarter annualised basis,the fastest pace of growth in two years and the sixth consecutive quarter of expansion. Driving the upswing is the feed through of ultra-loose monetary policy and fiscal stimulus. Despite these realised gains, there are limits to policy-led growth and Japan also faces structural headwinds of low inflation expectations and an ageing population.We therefore view the growth uptick as transitory and absent major reforms to tackle these challenges, Japan’s long-term growth trajectory remains highly uncertain.

Growth in Japan began gaining traction at the start of 2016when the Bank of Japan(BoJ) cut rates into negative territory and maintained its quantitative easing programme (QE). The BoJ loosened policy again in September 2016, adopting what has been described as a “Yield Curve Control” (YCC)regime through which it has sought to maintain the level of the 10-year bond yield around 0%. The net effect of these actions was to reduce the relative attractiveness of Japanese assets and thereby weaken the yen and boost Japan’s exports. The yen fell by 10% against the USD in 2016 and net exports drove 60% of real GDP growth in the year.

To take the pressure off monetary policy,the government has initiated a large fiscal stimulus programme in 2017 to support domestic demand. Public investment spending rocketed 21.9% on quarter over quarter annualised basis in Q2 2017reflecting major projects related to transportation and in preparation of the 2020 Olympic games.The stimulus has had a sizeable impact on consumption as well. Transfers to pensioners and low-income families, who have a high propensity to consume, have all been increased.

Japanese GDP Growth

(contributions to quarter over quarter growth, annualised; unless otherwise mentioned)

Given these substantial results over the past six quarters, why then do we doubt the sustainability of growth? There are four main reasons.

First, monetary policy may be close to reaching its limits. Japan’s QE programme is endangered by a declining supply of bonds left to buy.The BoJ already owns over 40% of the total stock of Japanese bonds in the market.External developments are also a threat to the BoJ’s effectiveness.US dollar weakness has counteracted Japan’s YCC regime thus far in2017, pushing the value of the yen up 7% since the start of the year.

Second,fiscal policy will add less to growth going forward. The initial impact of stimulus is typically large but as capital spending on Olympic projects stabilises,its value-added to the economy should begin to decline.

Third,inflation expectations are deeply entrenched at a low level. Despite massive policy intervention, record low unemployment and past depreciation of the currency, core inflation has averaged 0% so far in 2017 and has been on a downward path since 2015.Typically these factors would push up inflation as higher labour demand would bid up wages and firms would pass on the cost of higher imported goods to customers. However, after decades of sub par growth, Japanese firms – particularly corporations – have become extremely cautious. Instead of raising prices and wages, they have adopted measures to absorb higher costs and limit wage gains. This creates an systematic deflationary bias and poses a structural downside risk to growth which will likely require deeper labour market and corporate reforms.

Fourth, and perhaps most threatening, is Japan’s steadily declining population. The government estimates that the population could fall by almost 40m or a third of the current population by 2065. Japan has tried to compensate by increasing the number of foreign workers and the female labour participation rate but the pace of these gains will have to increase substantially and be sustained for decades to arrest the economic impact of population decline.

In short, Japan’s near-term strength may be obscuring the magnitude of its long-term challenges. Growth is expected to rise from 1.0% in 2016 to around 1.5-1.7% in 2017 but should decline thereafter as policy support fades. Until Japan figures out a way to overcome low inflation expectations and the effects of population decline, sustainable long-term growth will remain elusive.