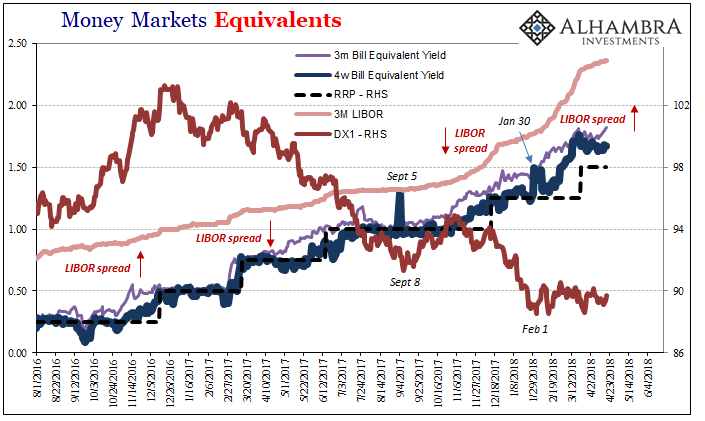

No one seems able to account for the rise in LIBOR-OIS. I think it’s a vain effort, and focuses on the wrong segments, but nonetheless there is considerable uncertainty which always casts suspicions into the shadows. That is important.

A few weeks ago, all the big bank analysts were alight with their theories. They couldn’t agree, as noted in this ZeroHedge article (thanks again T. Tateo). Despite the contributions of several market experts, actual experts for once, the only solid conclusion one might draw is that none of them really knows.

Only one, Bank of America) strategist Mark Cabana, seemed able to state the obvious:

We acknowledge these factors leave much to be desired and suggest that an unaccounted-for factor has been contributing to the recent market movements. However, the data available to us suggest BEAT is not the main culprit and that the aforementioned contributors and higher bill supply are likely the main drivers. [emphasis in article]

As I mentioned before, the FOMC’s patently ridiculous blaming of the bill issuance gets tossed around because they are the Fed. Even after all that has happened, none of which was supposed to happen if our central bankers were at all competent, their opinions on such matters are treated authoritatively anyway. It becomes lazy shorthand simply due to the fact no one will challenge what is nothing more than hollow pedigree.

Before continuing, let me be clear that I don’t know for sure, either. I am merely speculating along with everyone else, though I think based on a reasonably sound reading of the situation. What I present (have presented) seems to account for more of the facts than these others which account for only a limited set.

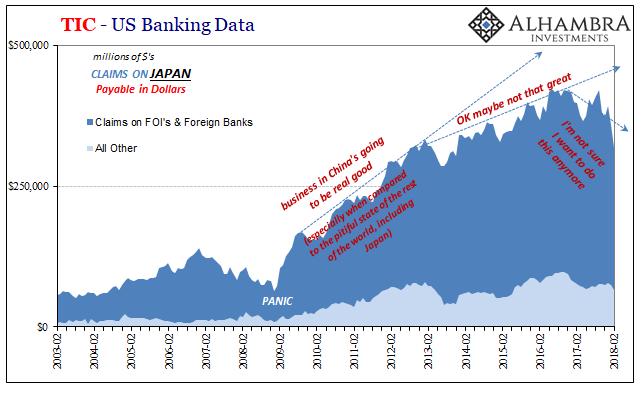

The big one is Hong Kong, but really beginning in Japan. I’m not the only who has noticed:

The pressures that have built since the start of this year on the Hong Kong dollar are reminiscent of what happened 11 years ago,” wrote Simon Derrick, chief currency strategist at US bank BNY Mellon last week, when there was also a widening of the spread between the Hong Kong and the London interbank offered rates.

What has been seen recently in Hong Kong is “a further echo of market behaviour a year before the global financial crisis”, Derrick said.

The so-called unaccounted-for factor looks suspiciously like conditions we’ve seen before. That can’t be for many of these analysts because the Fed has created so many bank reserves, several trillion, and therefore they will only consider even highly negative global monetary conditions as some benign quirk.

There’s a lot to work through, but in simple terms:

That doesn’t mean there’s a Japanese Lehman just around the corner, far from it, but aggressive expansion of their US dollar loan books could leave Japan’s banks exposed if US dollar funding conditions continue to tighten.

If? It’s not just a problem for Japanese banks, though, but also to those other banks who were being supplied by them. Those in China, for example.

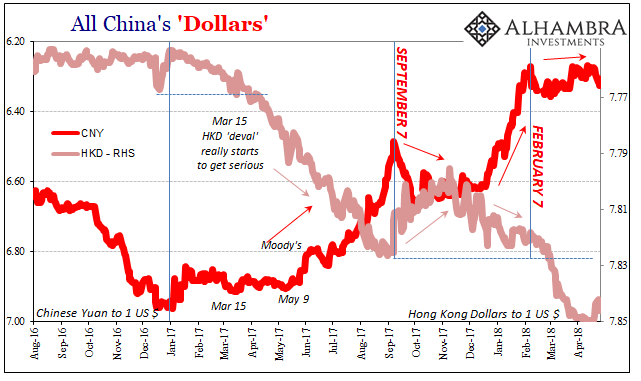

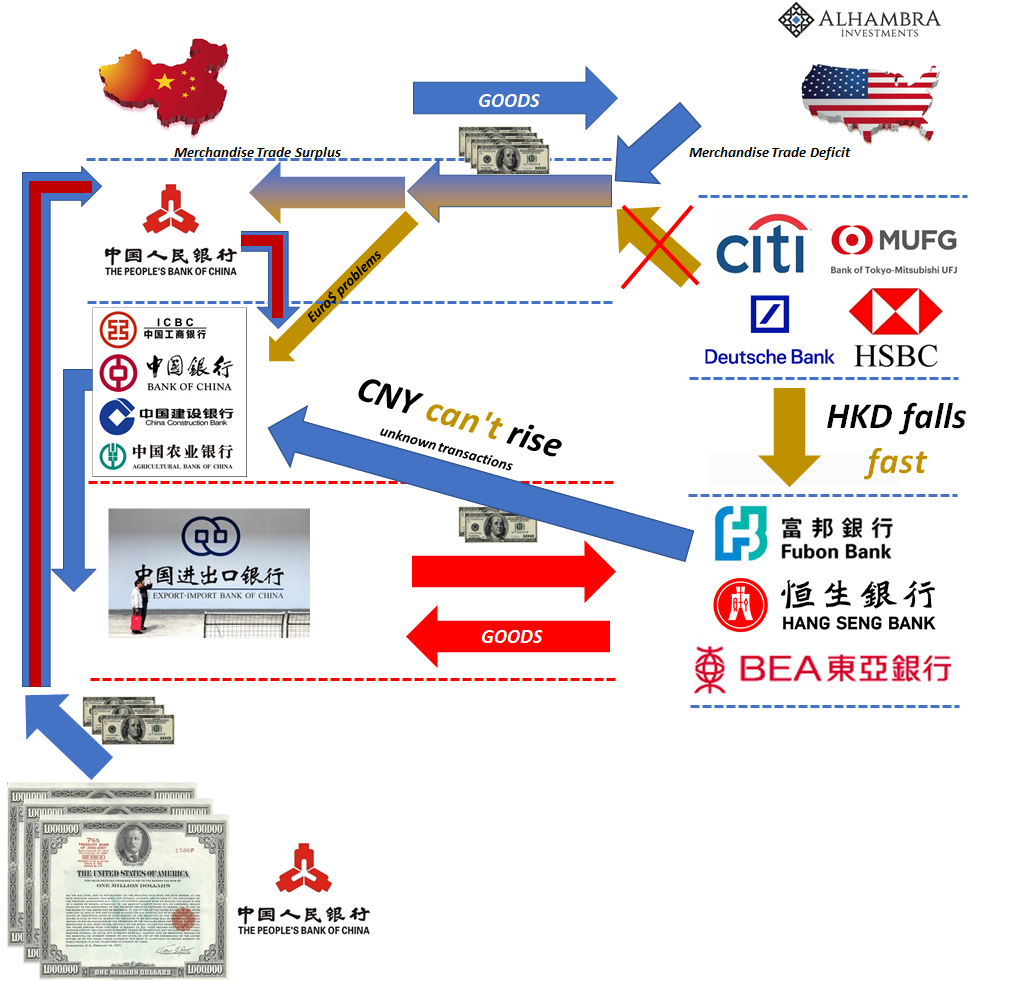

Enter Hong Kong. I’ve described China’s dollar short and the dangers it poses in situations of a dollar shortage; like one indicated by either liquidity risk indications (such as dramatically increased LIBOR-OIS) or just a plain rising dollar.

The problem presented to Hong Kong was to act as a bypass to these funding impediments. In reality, it was, I believe, to take pressure off the PBOC which was expending enormous “reserves” to maintain minimally operational “dollar” levels for the Chinese system. As noted earlier today, the PBOC is still bleeding forex assets, meaning that whatever might have been achieved by this circumvention was never enough. This is a very important point.

HKD falls as banks in the city increase their funding activities, while at the same time CNY rises because Chinese banks don’t have to bid for as much regular funding. Risk perceptions adjust both currencies a bit further in the same directions.

If conditions shift, however, what looks to have been a workaround starts to become contagious.

What was probably perceived as low risk on eurodollar markets is reassessed differently. Strains emerge not just with regard to HK activities, but also for those indirectly related (like, again, Japan). As it progresses this way, more and more pieces are pulled in like a vortex. We’ve already gotten to direct HKMA involvement.

Now you have two monetary authorities (PBOC & HKMA) rather than one directly participating in the decay. Both are now bleeding “dollar” assets by supplying them in place of private market capacity, and, we should note, doing so during a period that is otherwise considered healthy, even booming. It’s a bit of shock to those expectations, anyone holding them.

The mainstream issues further reassurances that nothing can be seriously disrupted here as everything is easily taken care of by central bankers and monetary authorities who hold at their disposals massive stockpiles, etc. That largely misses the point, which is that these public entities have already been drawn into what should be an exclusively private funding matter if everything was working properly. Therefore, in one sense it doesn’t matter how much, only that they are doing anything at all.

And in being reminded of that fact, we are also reminded the high degree of circularity it involves.

The chance of the George Soroses of the world succeeding in harming the peg is negligible. As its first line of defence, Hong Kong has US$440 billion in foreign exchange reserves, 1.4 times its GDP and almost twice its base money.

If that were not enough, Hong Kong has a big brother (Beijing) watching its back. A liquidity swap line with the People’s Bank of China, worth 400 billion yuan (US$63 billion), can be tapped straightaway. But Hong Kong ultimately has the backing of the world’s largest reserve arsenal at US$3.1 trillion.

In other words, the ultimate guarantor here is the same central bank that saw its own currency freefall (and absorb the enormous economic and financial consequences of that) given those same exact reserves and the same declarations founded upon them everyone put out in 2014 and 2015. The problem isn’t that central banks have them, it’s that we have seen time and again they don’t know how to effectively use them!

For over a decade now, what is assured is two things simultaneously: 1. That if central bankers have to get involved there is already a big problem. 2. When they do get involved it never ends well. I could add a third, that this is always “unexpected”, but that’s really derived from Points 1 & 2.

This was one of the primary developments of the 2008 panic; it was widely presumed before 2007 that whatever trouble the “dollar” world may get into the maestro’s Fed would be there to bail it out. It was the liquidity backstop of all liquidity backstops. And like so many other legends, it was proved as nothing more than hollow rhetoric.

As if intent on learning nothing, it was proved again in 2011 (especially the part of US$ bank reserves, the prize of QE, being essentially worthless in actual practice). And the once more in 2014, this time drawing in most if not all of Asia and EM’s like Russia and Brazil.

Now the PBOC is alleged to occupy the same role, having already performed in pretty much the same way as the Fed did in any of these episodes.

What we see is a desperately fragile system, not the least of which is due to this extreme mismatch between conventional perception especially relating to the ability of central banks to do their job. Unfortunately, for that to actually happen would require throwing the orthodox Economics textbook into the garbage and starting over on the money section.

Every once in a while, with almost assured regularity, markets though often buoyed by composed sentiment get reminded of this fact. It’s the great unaccounted-for global funding risk. Everyone says that there are these massive resources behind all these markets, far more than enough for every possible situation, but in the back of your mind you realize that they all come inextricably attached to central bankers.

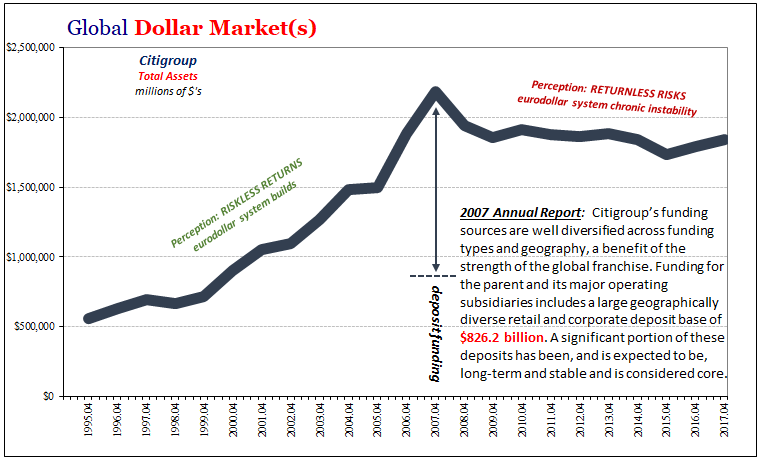

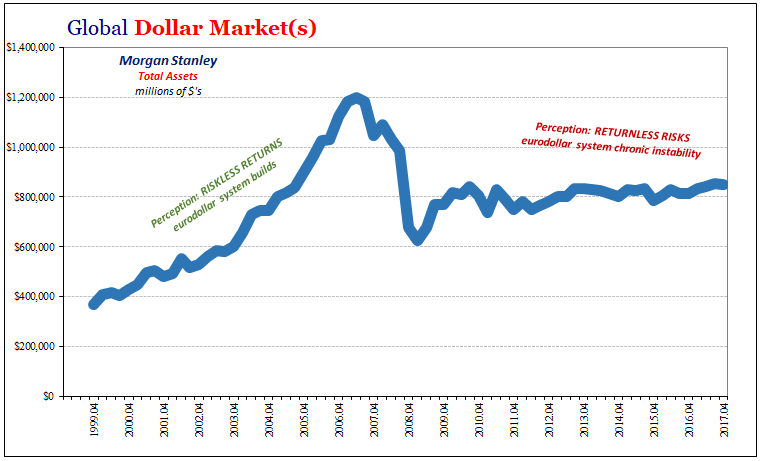

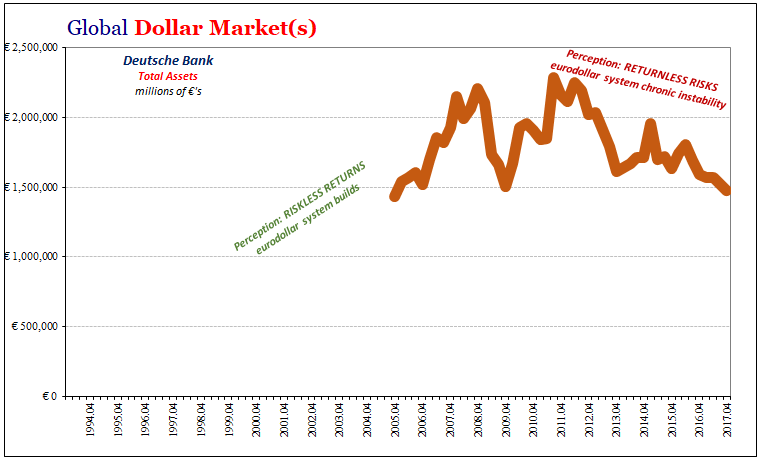

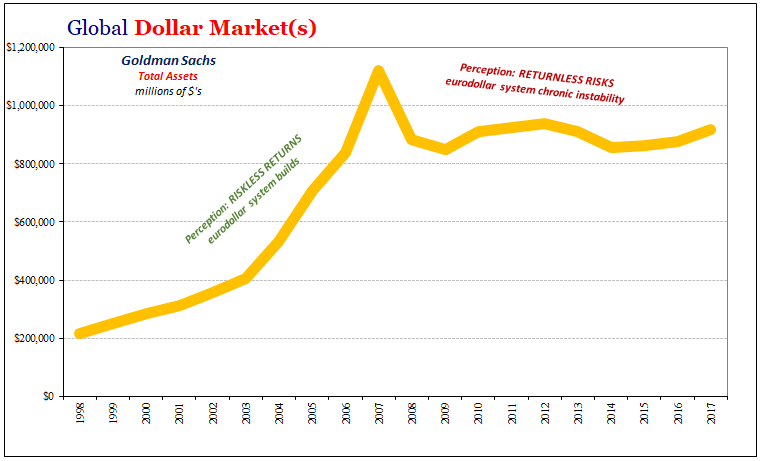

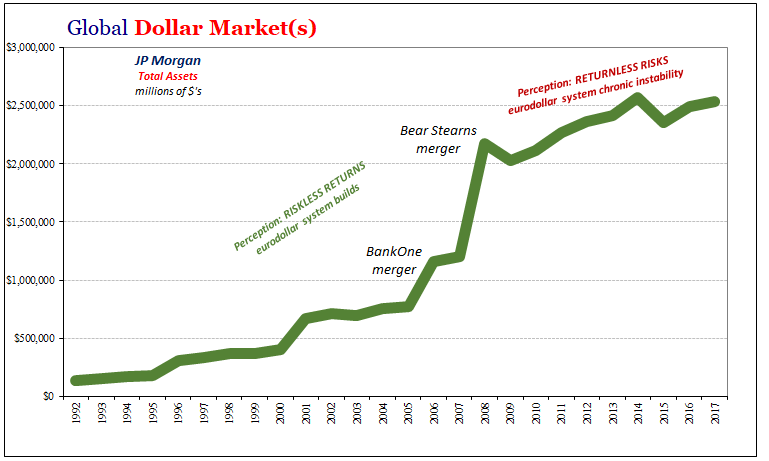

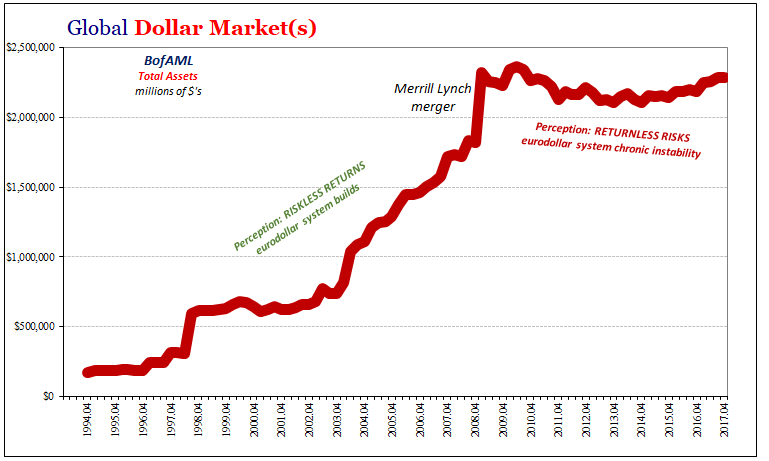

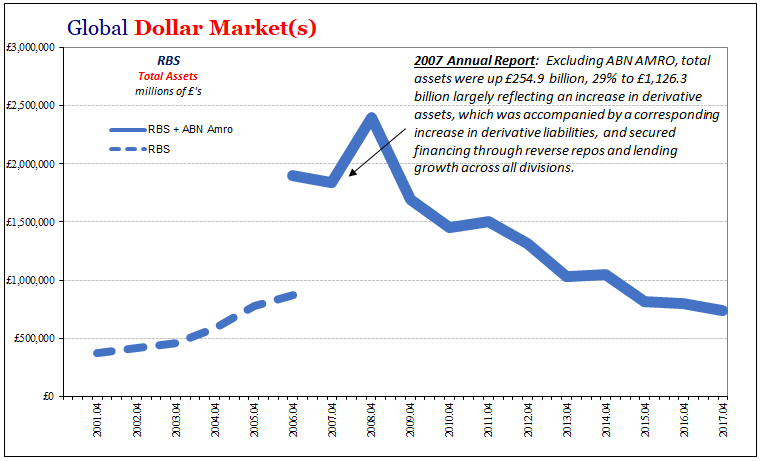

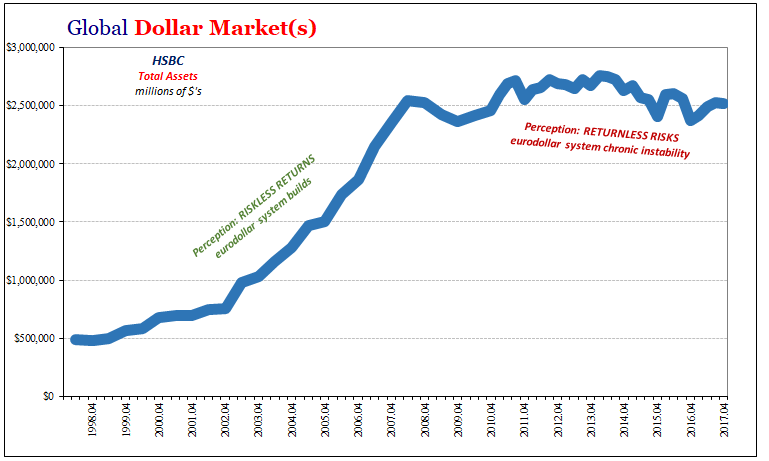

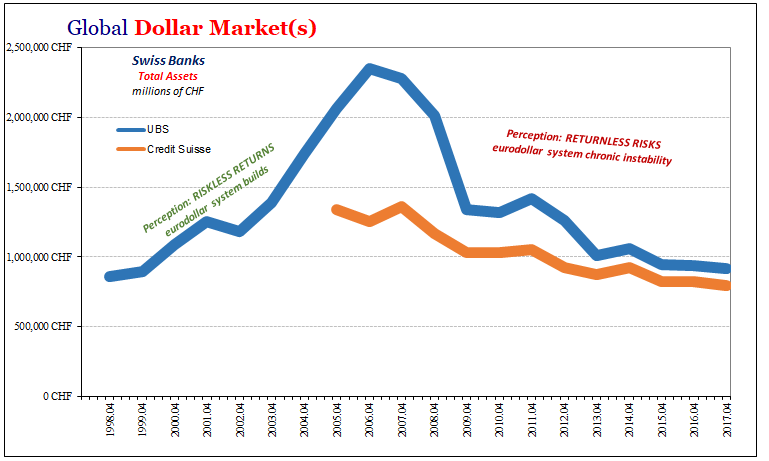

If a central bank is involved, there is the non-trivial risk it is already too late. No wonder banks only shrink. The only thing that really changes is that at times they tend to want to accelerate their shrinking. These, LIBOR-OIS or a rising dollar, are those times and balance sheet capacity is the real monetary stuff. It’s quite the track record central bankers have compiled.