The clues are starting pile up that the deepest phase of the economic loss for the US coronavirus recession has passed. There’s still a long way to go to climb out of the hole, but data published to date suggest the recovery process has started.

It’s unclear how the rebound will unfold and how long it will take, but for the moment markets are focused on the shift in trend—from down to up. Monday's stock market rally erased the year-to-date losses. A change in expectations is also showing up in the Treasury market.

Take the benchmark 10-year yield. After trading in a tight range in April and May, the 10-year rate jumped last week, rising to 0.91% on Friday (June 5), the highest since March 20. The yield ticked lower yesterday (June 8), but for the moment, the crowd appears to be reconsidering the risk of disinflation/deflation for the near term.

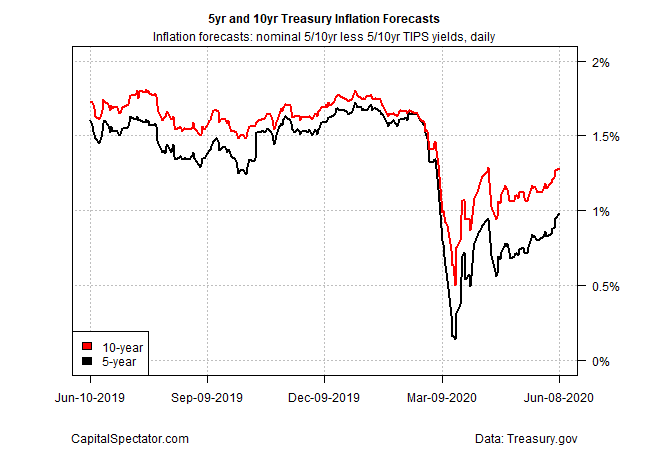

The Treasury market’s implied inflation forecast is showing even stronger upside rebound lately. The spread on the 5-year nominal yield less its inflation-indexed counterpart collapsed to 0.14% in mid-March to 0.14%. But in the weeks that followed, a sharp U-turn has been unfolding, lifting the crowd’s outlook to 0.98% on Monday (June 8).

The market’s inflation expectations are still low. Before the coronavirus crisis, the 5-year forecast was above 1.5%. The question is whether the reflation trade in recent weeks will continue and return to pre-crisis levels… and beyond?

If there’s a catalyst for repricing inflation risk, the surge in government spending is on the short list. As The Economist notes, “Never before have central banks created so much money in so little time.” In the US, over the past three months, “America’s monetary base has grown by $1.7 trillion, as the Federal Reserve has hoovered up assets using new money.”

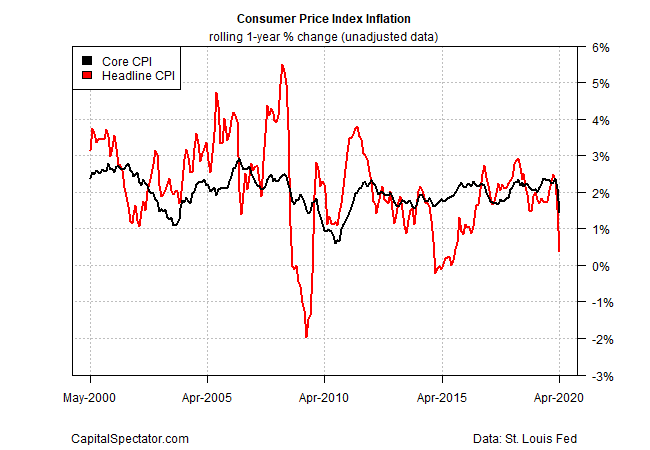

The unprecedented surge in government largesse in the space of a few months to offset the coronavirus recession has sparked predictions that higher inflation is all but assured. The immediate risk is still disinflation, as the economy struggles to recover after suffering the deepest loss since the Great Depression. But it’s becoming increasingly clear that a snap-back is underway, which is fueling expectations that pricing pressure may eventually heat up.

If reflation risk is lurking, it’s not on the immediate horizon, or so economists predict. Tomorrow’s May report on consumer inflation, for instance, is expected to show that headline inflation will remain unusually weak at a year-over-year rate of just 0.2%, down a tick from April’s 0.3% trend, based on Econoday.com’s consensus point forecast.

But markets are always looking ahead and there’s a growing preference to price in a rebound in pricing pressure in some degree for the foreseeable future. BofA Global Research’s Mark Cabana told CNBC that last week’s surprisingly strong data on employment growth in May will keep the reflation trade bubbling.

“We were really thinking that the economy would still really struggle to rebound in Q2, slowly begin to grow in Q3 and then more meaningfully be rebounding in Q4 ... But the risk is it all happens sooner, and that would be a pleasant surprise.”

Cabana’s current forecast: the 10-year Treasury Note yield (currently at 0.98%) will reach 1.0% by this year’s end and 1.25% at the end of the first quarter of 2021.

“We still feel quite confident in that,” he said. “If anything, the risks are that the timing of that one percent 10-year could move forward much faster than we had thought.”

Lubos Pastor, an economist at the University of Chicago, explains that the government has an incentive to favor higher inflation as a tool to manage debt-servicing, in the wake of a hefty increase in spending.

“During this COVID crisis, governments are accumulating huge amounts of public debt."

“In many countries, the debt-to-GDP ratio will rise by 20 percent or more. The question is, how do we deal with this mountain of debt?” One possibility: “let inflation run above expectations for a while.”

His rationale is inflation can reduce the real burden of public debt. For example, after World War I, Germany famously inflated much of its domestic debt just by running hyperinflation. Now naturally, we’re unlikely to see hyperinflation nowadays, but if inflation were to run a bit above expectations—instead of 2 percent, maybe 3 percent or 4 percent for a while—that would help reduce the real burden of debt.

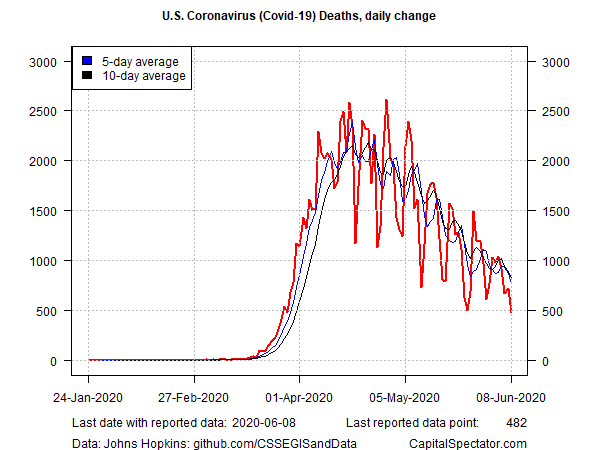

These are still early days for assuming that the US is on track for a robust and swift recovery and so, the inflation narrative remains open for debate. But the Treasury market is considering the possibility that pricing pressure may be heading higher in the months and years ahead. Much depends on how quickly and broadly the economy rebounds. In turn, a critical variable is how the Covid-19 health crisis evolves.

At the moment, the trend looks encouraging. For example, the daily change in US Covid-19 deaths fell to 482 on Monday (June 8), a new post-peak low. Good news, although several key unknowns are still lurking, including the big question: will there be a second wave of infections in the fall and winter?

High inflation may be coming, but it’s still premature to assume that such a future is on a strict timetable. Nonetheless, it’s significant that the Treasury market is considering an alternative outlook beyond deflation.