The past few years has seen the prices of real estate in New Zealand skyrocket as a combination of historically high immigration and capital flows largely predicated by QE, have impacted the local market. In addition, the local political scene has largely complicated efforts to increase the supply side which has put further upward pressure on market equilibrium.

Subsequently, prices have neared impossible levels in a relatively short period of time and the Reserve Bank now appears to be quietly attempting to let some air out of the balloon lest it threaten financial stability within the small island nation. The latest rhetoric from the venerable central bank has focused largely on moving beyond LVR limits to focus upon debt to income ratios.

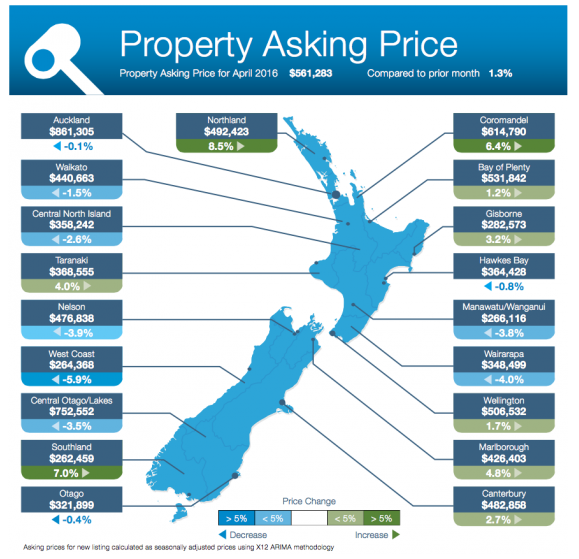

Historically, the introduction of such controls has made it relatively difficult to borrow in buoyant markets. In fact, given that the average house value in the Auckland property market now exceeds $861,305 any introduction of income solvency tests would likely have a relatively stark impact on demand.

Source: unconditional.co.nz

However, any move towards the introduction of such a regime would require alterations to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the government. Subsequently, news out today that the central bank is currently negotiating with the NZ Finance Minister of introducing new powers to their MOU is timely indeed. It is clear that the central bank is spooked by the spectre of a property collapse and what it could potentially do to the NZ banking system.

Subsequently, it is probable that any new MOU negotiated between the parties will contain a range of measures that exceed a simple debt to income ratio regime. This is especially salient given that there is currently a stark lack of leadership from the government over the inherent risks within the New Zealand property market. Therefore, it would appear that the RBNZ is ready and willing to use whatever tools are at its disposal to reduce what they clearly see as an asset bubble that threatens the banking system.

So the question remains as to what impact the introduction of debt to income rations would have on the bubbly Auckland real estate market. The reality is that it may help to stave off some of the risk within the banking system at the cost of access for low and middle income earners. In addition, it could actually stagnate building and construction within the region as it starts to slow price gains.

Ultimately, it needs to be realised that demand is relatively inelastic for housing within Auckland and what is really needed is a boost to the supply side. Subsequently, the key to “popping” the current bubble is increasing supply whilst reducing the local and national government’s regulation of building and urbanisation. In short, the market is quite capable of sorting itself out and rebalancing over a period of time if the artificial barriers through regulation that exist for land and construction are removed.

In closing, the RBNZ’s new set of tools might not crush the market just yet, but it will take out some of the heat whilst at the same time igniting a national debate on removing some of the regulation that exists around land use in New Zealand.