Tin producers would obviously like to think so and recent developments may suggest they have grounds for optimism in 2016.

According to the World Bureau of Metal Statistics (WBMS) the global tin market recorded a deficit in the first 6 months of the year of 18,500 metric tons. Both refined Asian production and Chinese consumption were down for a number of reasons, but in spite of the deficit the price took a hammering along with the rest of the commodity sector.

The Tin Dynamics

Chief among the reasons for this battering, it would be easy to say, was a selloff across all metal categories due to the slow down in Chinese growth and fears over the state of the Chinese stock market. Yet, tin has some specific dynamics all its own that have contributed to price falls of nearly 40%.

Source: Kasbah Resources

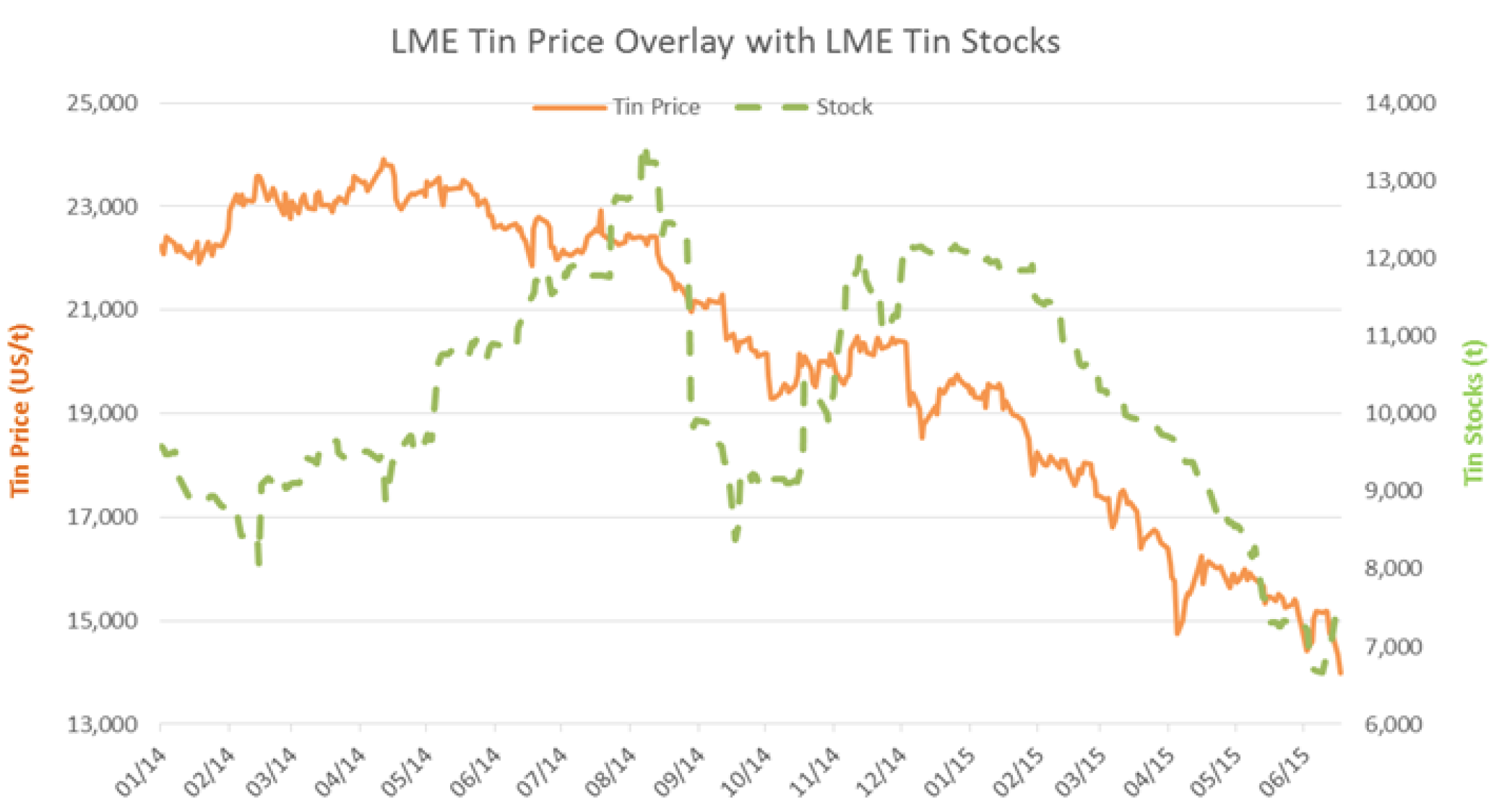

Exchange inventory though has, at least since summer, been falling just as fast. To say this alone is a sign of a tightening market is too simplistic, especially for such a small niche market as tin, but it suggests there may be less metal around should refined supply be reduced in the future.

Tin has, arguably, been even more polarized over the years than any other metal. Supply from Indonesia and demand from China were, until recently, the beginning, middle and end of the supply demand equation, but much has changed in recent years. Not the least of which is Indonesia’s raw material export ban.

As a result of Indonesia’s various legislative actions, exports have fallen. There have been 3 changes to export regulations over the last 2 years mostly aimed at channel sales through the Indonesia Commodity and Derivatives Exchange (ICDX) in an attempt to control the sale of tin onto the world market and, hence, prices.

Trying to Legislate Away Smuggling

In addition, Indonesia has been rightly worried about the scale of illegal tin mining and smuggling and the environmental damage it can cause. Only by channeling mining and export through approved channels, they argue, can the damage be curtailed.

Every time there is a change in rules there is a surge in volumes as companies find a loophole they try to exploit before it gets closed off, but while there are short-term gyrations in the medium term, volumes fall. From 2006-7 to the forecast for this year volumes have dropped from greater than 120,000 mt to some 73,000 mt now according to the Australia-based tin producer Kasbah Resources (ASX:KAS) in their recent annual report.

Falling prices, though, have also had an impact on supply, causing contraction from tin producers not just in Indonesia but higher-cost locations in South America and Africa. Fortunately for tin consumers, while supply may be under pressure from traditional sources, new mine supply from Myanmar has been rising.

How Much Tin is In Myanmar?

Estimates for 2015 put supply of mostly low-grade ore and concentrates from Myanmar’s northeast region at 35,000-38,000 mt up from about 30,000 mt last year, and according to Reuters, half that the year before. This has provided a steady stream of cheap, if low-grade, ore going into the Chinese refining market where it is consumed domestically or re-exported as refined metal.

Kasbah suggests commodity fund speculation has also played a part in depressing the tin price, saying speculators find it easier to build positions in small volume markets like tin than much larger markets such as copper, zinc or aluminum, allowing markets to be shorted when the fundamentals look poor, driving the price down.

The reverse, of course, could be true if the market looks like it may tighten. That will require speculators to see a change in supply and demand, difficult when the swing supplier is a place like Myanmar.

The contraction of traditional supply sources and shelving of new projects has so far failed to have much impact on the price, although they may explain the fall in exchange inventories. China’s new supply source in Myanmar, though, is a known unknown in as much as we have little visibility into how much more production China can extract on an annual basis.

So far, Myanmar has made up for much of Indonesia’s gradual decline. If it has the potential to double output in the years ahead, then even the loss of supply from traditional sources due to the currently low prices may not, in itself, be enough to restrict supply, but much will depend on demand and for global growth that will be the key.

by Stuart Burns