As the Federal Reserve prepares to start raising interest rates, history lurks in the background amid an inflation surge that’s remained more persistent than expected.

The standard treatment for a run of inflation that’s become too hot to tolerate is to adjust monetary policy to fight the beast. Invariably that shift translates to higher interest rates, which often leads to recession. Not immediately, but the apparent causal link between a rise in the Fed funds target rate is hard to ignore.

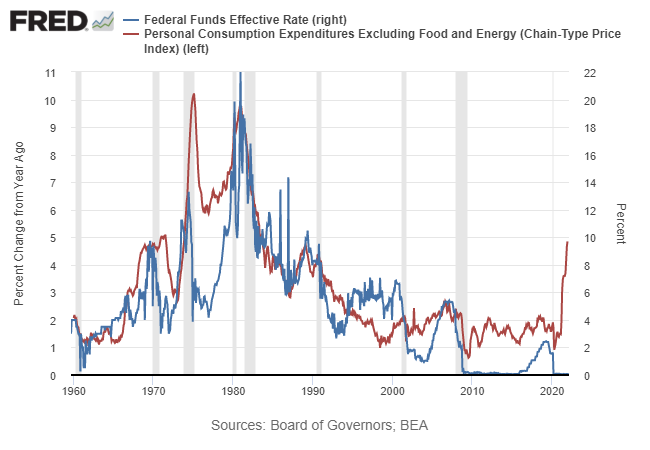

In the chart below, a runup in core PCE inflation tends to break either during or soon after economic recessions. It’s not clockwork, but neither is this a random relationship. So the question of how to assess future risk arises anew as the start of a new policy regime is set to begin when the Fed rolls out a new policy announcement on March 16.

Lest anyone doubt the accumulating hints that the central bank has been dropping, a fresh wink wink nod nod was offered yesterday, when Cleveland Federal Reserve President Loretta Mester advised:

“Each [FOMC policy] meeting is going to be in play. We’re going to assess conditions, we’re going to assess how the economy’s evolving, we’re going to be looking at the risks, and we’re going to be removing accommodation.”

Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic offered a similar analysis this week, explaining that

“In terms of hikes for the interest rates, right now I have three forecast for this year. I’m leaning a little towards four, but we’re going to have to see how the economy responds as we take our first steps through the first part of this year.”

There’s no law iron-clad law that dictates that a central bank that pivots to fight inflation (as opposed to the long-running effort to raise inflation that’s now ended) is destined to trigger recession. But history suggests the odds aren’t exactly low for predicting otherwise. Lisa Shalett, chief investment officer of Morgan Stanley) Wealth Management, in December observed:

“The Fed knows what to do, but they don’t necessarily know how to do it without squashing the economy.”

Will it be different this time? Possibly. Using history as a guide to the future for real-time economic analysis is fraught with many caveats. But as a starting point for discussion it’s useful to ask if the current runup in inflation will lead to a policy mistake that triggers a recession? Stranger things have happened.

Are higher interest rates enough to tip the economy into recession? No, at least not yet. There’s enough forward momentum to keep the expansion humming. But that appears to be true ahead of most if not all downturns and so we should be humble about assuming that we can see around corners or that today’s analysis will stay fresh through next week.

That leaves the standard approach: monitoring the economy in real time and applying informed nowcasting analytics to routinely evaluate (and re-evaluate) recession risk across a broad, diversified set of numbers. It’s still impossible to accurately forecast the timing of future recessions, much less their severity or duration. That leaves the only game in town: carefully estimating the odds that a new recession has started, and reassessing each day.

Those odds are currently low, based on a broad set of indicators and various econometric techniques. But here’s one forecast you can count on: the analysis will continue to fluctuate.

Meanwhile, it appears that the central is in a bit of a pickle. As Desmond Lachman, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, observes:

“The Fed has got itself into the most unenviable of monetary-policy dilemmas.”

If it fails to raise interest rates aggressively now, it risks allowing both inflation expectations to become entrenched and further froth to be added to already bubbly asset and credit markets. That in turn would set the US up for an even harder economic landing down the road than if it now acted in a timely manner. On the other hand, if it were to raise interest rates aggressively now it might succeed in getting the inflation genie back into the bottle, but at the price of bursting today’s everything asset-price and credit-market bubble.

Choices, choices amid so much imperfect real-time information. Alas, no one knows what the optimal policy choices on any given day, in part because no one has a full boat of reliable information on business cycle conditions in the present or near-term future. It’s not exactly flying blind, but it’s close, at least on some days. It’s always obvious what should have been done several months earlier. But as every central banker knows, it’s the present that forever bedevils and plagues the best laid plans of policy choices.