Japan 10-Year-year government bond yield is hovering around 0.5%, an all-time low.

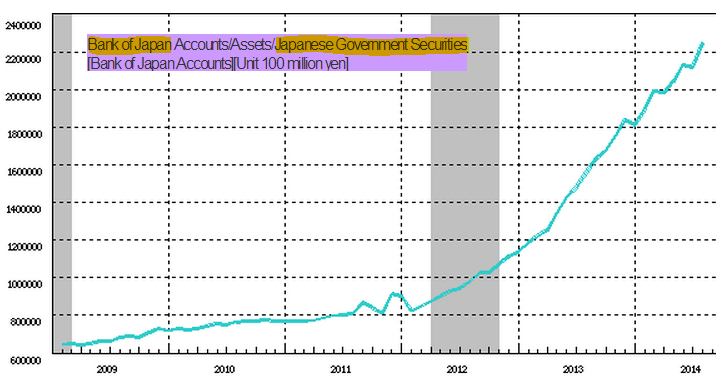

Clearly this is the result of the Bank of Japan's unprecedented securities purchases via the ongoing quantitative easing (QE) program that was accelerated last year.

While a number of economists such as Paul Krugman fully support this effort as a way of exiting the so-called "liquidity trap", the central bank's purchases are eroding the JGB market.

The Economist: - The BoJ is buying ¥7 trillion ($67 billion) of JGBs a month. It now owns a fifth of the government’s outstanding debt. Trading volumes have fallen dramatically, as has volatility in prices. One day in April there was no trading at all in the most recent issue of the benchmark ten-year bond.

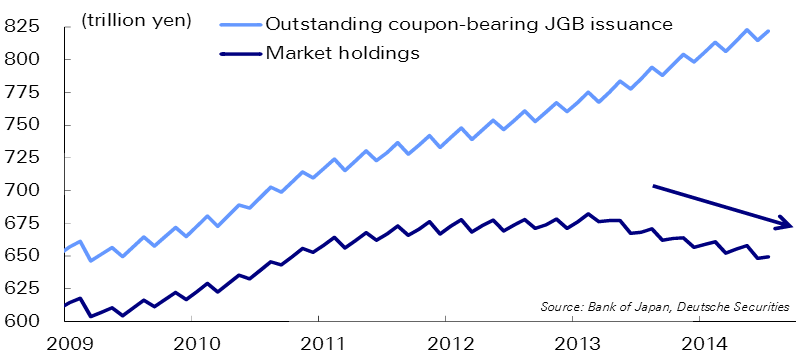

Last year's QE acceleration has begun to take more securities out of the private market than is being issued by the government.

The Bank of Japan was hoping that as yields decline, the banking system will begin replacing JGBs it holds with loans to the private sector, thus stimulating growth and releasing more bonds into the market. But banks have been slow to get out of JGBs.

The Economist: - Part of the reason that bond prices remain high is that financial institutions have not sold as many JGBs as the BoJ had hoped. It had assumed that falling yields would prompt banks to shift their holdings into riskier assets, stimulating the economy. Although Japan’s biggest banks sold JGBs in the months immediately following the BoJ’s first purchases in 2013, they have now largely stopped. Regional banks, the most notorious JGB-addicts, hung on to their bonds, and are now purchasing more.

With rates on private sector loans now also at historical lows (around 0.8%–0.9% according to DB) and the overall private inventory of government paper declining, JGBs remain attractive on a relative basis, even at current rates. In fact, measured in terms of returns on regulatory capital, private sector lending looks terrible. Just as the case in the Eurozone, holding government paper is quite rational for banks.

Moreover, markets are pricing in an ongoing QE effort for the foreseeable future, which will end up taking even more paper out of private hands.

Deutsche Bank: - ... note that implied volatility in the JGB futures market is now abnormally low, which would appear to reflect a general expectation that the BOJ will persist with its massive bond-buying operations indefinitely. Put simply, very few market participants currently believe that the central bank is capable of achieving its +2% "price stability target", and therefore assume that it will remain in easing mode for the foreseeable future.

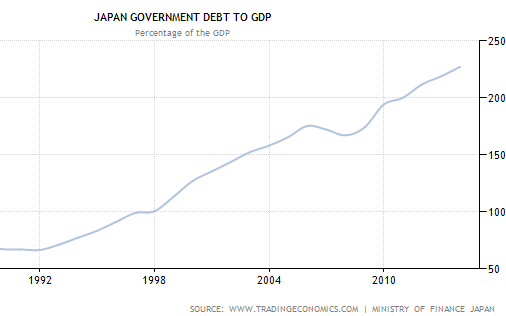

Exiting this program in a market that has become increasingly dysfunctional will be more difficult and disruptive with time. And given the government's unparalleled debt problem, is exit from QE even possible without nudging the "unsustainable equilibrium" (vicious circle of rising rates and rising debt burden)?

Japan has moved from Paul Krugman's liquidity trap to Haruhiko Kuroda's "indefinite QE" trap.