This blog post was originally published on BRINK “Deleveraging” is the new buzzword in China. The leadership clearly wants to scale back its epic borrowing, but it is not necessarily ready to pay the price for it, namely, the price of having less support for growth. The question is whether the recent efforts of China’s leadership to […]

“Deleveraging” is the new buzzword in China. The leadership clearly wants to scale back its epic borrowing, but it is not necessarily ready to pay the price for it, namely, the price of having less support for growth. The question is whether the recent efforts of China’s leadership to force the deleveraging of its economy are bearing fruit.

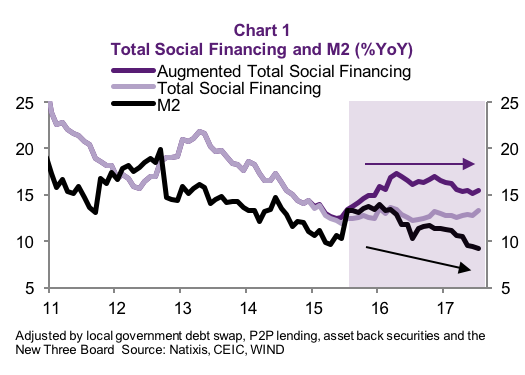

Among China watchers, the most optimistic have announced the beginning of the deleverage process based on the rapid deceleration of the M2 money supply. However, this is indeed an excessively narrow measure of leverage as the bigger picture gives a very different message. This is because most of the leverage is happening outside the banking system.

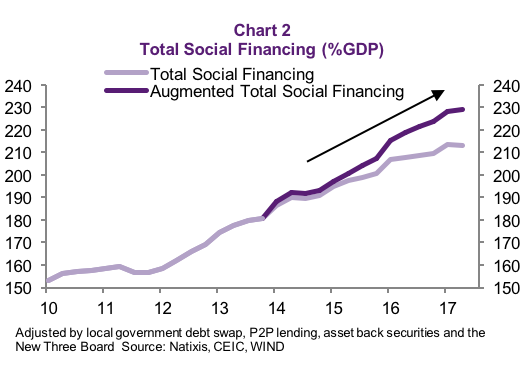

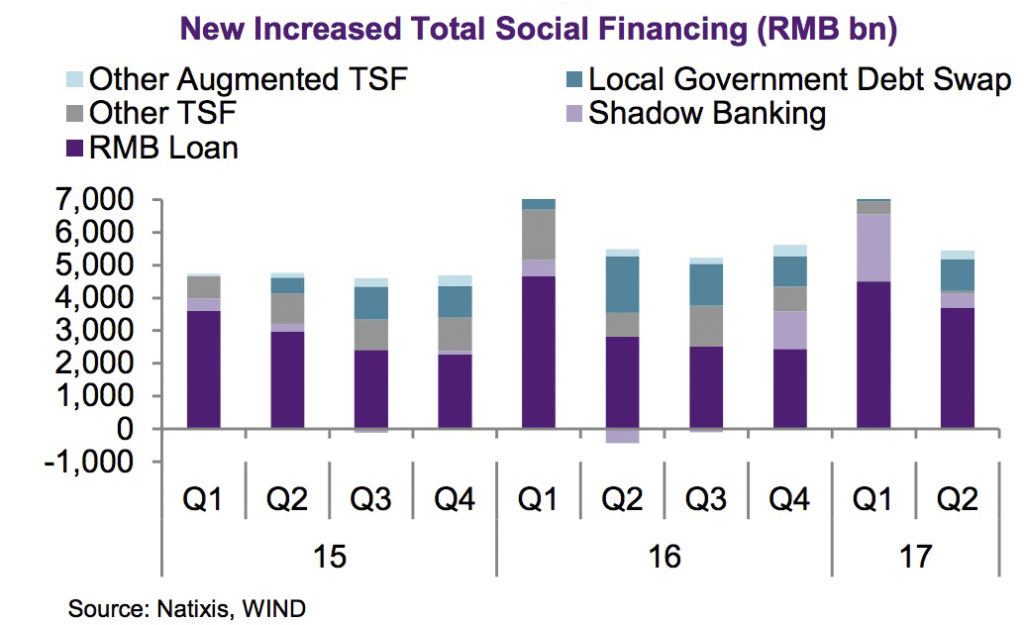

In fact, broad measures of the size of credit being granted to the Chinese economy, such as the People’s Bank of China’s (PBoC) own compilation of total social financing (TSF), a broad measure of credit and liquidity in the economy, point to credit still piling up faster than nominal GDP. This is even more the case when we move beyond the PBoC’s official definition to include other forms of shadow banking. In fact, the extended measure of TSF has grown as much as 11 percentage points of GDP during the last year, reaching 231 percent as of July 2017.

On this basis, it seems too early to talk about deleveraging of the Chinese economy. The reason is simple: Credit in the economy (TSF and even more so our augmented measure of TSF) continues to accumulate at a faster speed than nominal growth. In addition, the mirror of credit, namely debt continuing to pile up, not only for businesses but for household and government, too, reached 257 percent of GDP at the end of in 2016.

The only good news is that the leverage process appears to be slowing down, but this is subject to uncertainty given the rise of new shadow banking products for regulatory arbitrage, which could soon outdate our newly created measure of TSF. If anything, it points to huge financial innovation skills, but not to deleveraging as is frequently stated. M2 is clearly no longer a comprehensive enough measure.

All in all, the present slower leveraging speed does not seem to be enough to halt China’s credit addiction. Other concurrent measures, such as the growing number of debt-to-equity swaps to lower state-owned enterprises’ debt burden, seem to have provided some relief for heavily indebted businesses. Still, the medium-term sustainability of such a plan is based on businesses’ ability to regain their profitability.

Overall, it seems difficult for China to truly engage in a deleveraging process without accepting a lower—but more sustainable—real growth rate.